VALLAS FACTS: How 'Chainsaw Paul' got de-chained when 'Chainsaw Al Dunlap' was exposed as a pre-Madoff crook who cooked the books. While business reporters were blowing the whistle on Dunlap, education writers created the Vallas myth by praising Vallas's cooking of the books and macho bluster

It was hagiography, not really journalism. But as the 1990s progressed, more and more business, financial and economic reporting was reduced to a kind of celebrity drivel: CEO portraits and CEO worship. During the frenzy of corporate propaganda in the late 1990s and early 2000s, everyone knew that a legitimate career goal for a bright young man was to become a "CEO" -- preferably the CEO of a Fortune 500 corporation.

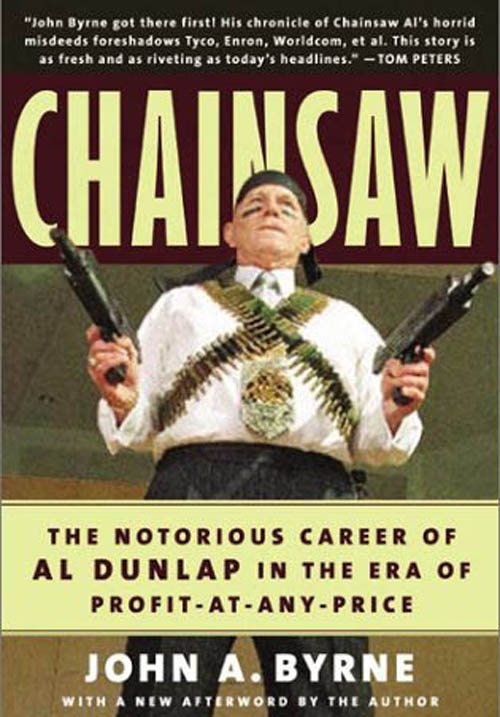

John Byrne's Business Week reporting on Al Dunlap finally became a book and helped the public not only to understand that Dunlap's "Rambo in Pinstripes" macho nonsense was a publicity stunt, but that the public image cultivated by Dunlap was ultimately bad for the corporation he ruined, Sunbeam. Like Dunlap, Paul G. Vallas specialized in macho posing, phony histories of himself, and claims that cutting could make schools better, just as corporate cuts according to Dunlap could make corporations better. After Forbes tried briefly to nickname Vallas "Chainsaw Paul" in early 1998, the collapse of Sunbeam and the macho "Chainsaw Al Dunlap" brand in 1998 made Vallas withdraw from that nickname -- while keeping most of the poses that Dunlap had mastered for a gullible group of reporters. Even after Vallas was dumped by Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley and the growing evidence of his failures in Chicago became more and more facts of history, Vallas's ruling class apologists and a handful of reporters kept his reputation as a fierce public schools "turnaround" specialist in play until a lawsuit in Connecticut in 2013 may have finally ended the Vallas Hoax. Business magazines -- and following them, the popular press -- were stuffed with ads. Meanwhile, like a prelude to the Kardashians, the covers of the magazines featured the latest celebrity CEO, a master of the universe. There were dozens, filling celebrity pages that capitalists once shunned. Jack Welch of GE was not only remaking one of the nation's largest industrial corporations, but preaching a version of management that was a worthy predecessor of "Race To The Top." Management by fear and humiliation.

John Byrne's Business Week reporting on Al Dunlap finally became a book and helped the public not only to understand that Dunlap's "Rambo in Pinstripes" macho nonsense was a publicity stunt, but that the public image cultivated by Dunlap was ultimately bad for the corporation he ruined, Sunbeam. Like Dunlap, Paul G. Vallas specialized in macho posing, phony histories of himself, and claims that cutting could make schools better, just as corporate cuts according to Dunlap could make corporations better. After Forbes tried briefly to nickname Vallas "Chainsaw Paul" in early 1998, the collapse of Sunbeam and the macho "Chainsaw Al Dunlap" brand in 1998 made Vallas withdraw from that nickname -- while keeping most of the poses that Dunlap had mastered for a gullible group of reporters. Even after Vallas was dumped by Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley and the growing evidence of his failures in Chicago became more and more facts of history, Vallas's ruling class apologists and a handful of reporters kept his reputation as a fierce public schools "turnaround" specialist in play until a lawsuit in Connecticut in 2013 may have finally ended the Vallas Hoax. Business magazines -- and following them, the popular press -- were stuffed with ads. Meanwhile, like a prelude to the Kardashians, the covers of the magazines featured the latest celebrity CEO, a master of the universe. There were dozens, filling celebrity pages that capitalists once shunned. Jack Welch of GE was not only remaking one of the nation's largest industrial corporations, but preaching a version of management that was a worthy predecessor of "Race To The Top." Management by fear and humiliation.

Dennis Kozlowski was spinning one of those "rags to riches" stories. Kenneth ("Kenny Boy" to the President of the United States until it became "Kenny Who?") Lay of Enron proved that the world's best corporations were "asset lite" and nobody guffawed. Or dug a little deeper -- until it was too late. Edison Schools Inc. was fleecing shareholders for a year or two on the public exchanges until its owners dumped the stock they had pumped (with the help of the "analysts" at outfits like Merrill Lynch) and then dumped quickly enough to make another small fortune for Chris Whittle while his shareholders watched their "shareholder value" drop like a rock in a cesspool from more than $30 a share to less than a buck a share within a few weeks -- before EDSN was "delisted" from the NASDAQ.

And then there were Paul Vallas and Al Dunlap, both, for a time, sporting the tough-guy nickname "Chainsaw."

Few celebrity CEOs of the 1990s received as much ink as Al Dunlap. By the end of his career, Dunlap was prancing around as "Chainsaw Al," the guy who knew how to cut "fat" out of any corporation and "increase shareholder value" -- based on the narrowest definition of what a corporation is for and a bunch of cheap accounting tricks.

By the 1990s, America's definition of the purpose of a corporation was so narrow that Adam Smith, a stern Protestant, would have rolled his eyes, while the Al Dunlaps of the USA were invoking Smith's book as the reason for their crooked schemes. That definition of corporate reality is still around in the second decade of the 21st Century, but even with the U.S. Supreme Court of 2013 has been challenged more and more. Most social critics now demand that the protections received by a corporation from a government and society require a broader sense of the duties of a corporation -- and its CEO -- than was served up during the Atlas Shrugged frenzies of the 1990s. Then came the bubbles bursting, first with individual corporations and other entities that had been defrauding (EDSN to Sunbeam to World Com to Enron... long list) marks caught up in the frenzy of stock investing knowing that JDS Uniphase was going to double again in the next 60 days, blah blah blah. At the same time, the smart money was chasing a guy named Berne Madoff around Palm Springs and Delray Beach, looking to get into his "returns"...

Corporate America had "Chainsaw Al Dunlap" until his whole scam collapsed and took Sunbeam with it.

Education America got "Chainsaw Paul Vallas," but the reporters covering "education reform" didn't have the same accountability measures to catch Vallas, so his scam lasted more than a decade longer than Dunlap's. But they were both narrated along the same lines.

From the moment Chicago's mayor appointed Paul Vallas as the CEO of CPS, the corporate media mythmaking machine went into high then higher gear.

The Forbes magazine story, in early 1998, was almost typical -- a careful blending of staging and hokum, praising Chicago's schools CEO, Paul G. Vallas and suggesting that he too receive the nickname "Chainsaw." Trouble was, the "Chainsaw Paul" fiction appeared at an inopportune time for celebrity CEO storytelling.

As Forbes was going to press with its "Chainsaw Paul" piece (reprinted below in full), the original "Chainsaw," Sunbeam corporation CEO Al Dunlap, was being exposed as the fraud he had probably been all along.

As Sunbeam collapsed following the revelations about how Dunlap cooked the books and inflated sales, the revelations poured out about how Dunlap cooked the books -- while he worked the press, creating an image of tough guy invulnerability that helped insulate him from the scrutiny that might have saved Sunbeam shareholders hundreds of millions of dollars.

That was still pre-Enron and pre-Bernie Madoff, but the expose of Al Dunlap's lies, to those paying close attention, foreshadowed a lot of the sorrow that was to come.

In April 1998, Forbes ran a lengthy piece (see below), preparing the "next level" of mythologizing Paul Vallas.

By the time Forbes was running its hagiographic silliness (below, the business press had noticed that everything about Al Dunlap's work at Sunbeam was a problem, then with a little digging proved it was a fraud.

By mid-1998, just as Forbes and other business publications were trying to baptize Paul Vallas a public sector "Chainsaw" it became clear the the "Chainsaw Al" brand had been tarnished, for good.

Never one to remain loyal to another person's story, Paul Vallas was never going to be "Chainsaw Paul" even though his silly tough-guy stuff was from the same scriptings that produced the "Chainsaw Al" stories for years.

FORBES1998 CHAINSAW PAUL ARTICLE. 4/06/1998 @ 12:00AM Chain Saw Paul

PAUL VALLAS is running the Chicago public school system the way Al Dunlap attacks a new company -- with a chain saw and plenty of publicity.

Wearing a black wool cap pulled down against the biting chill of a Chicago winter morning, Vallas bounds up to the doors of tenements on the city's gritty South Side. He tries to convince truant children to come to school. A gang-related shooting at Mary C. Terrell Elementary School in January had scared kids away.

Vallas' presence in a tough neighborhood, where VIPs are a rare sight, sends a powerful message to children and parents. Soon the lanky, bespectacled Vallas, 44, leads a pint-size parade of orange and green parkas across a dirt lot littered with broken bottles, and into the school.

Once one of the nation's most ineffectual, neglected and corrupt public education systems, Chicago's -- with 428,000 students in 559 schools -- is now a model of sorts for urban public education. If one person deserves credit, it is this Chicago-born offspring of blue-collar Greek immigrants.

Chicago schools suffer, in heavy doses, all the ills of urban school districts: poverty, gang activity and teen pregnancies. Chicago high schoolers taking the American College Test scored in the bottom quartile in the country. Grade-schoolers fared only slightly better, with less than a third reading at or above national norms.

Under Vallas, elementary school reading and math test scores, though still low, are at seven-year highs. Truancy has been down three years in a row. Before Vallas took over, only 61% of seniors graduated; now 65.2% do. The dropout rate, three times the national average, has stabilized at 16% after climbing for a decade.

In a way, things could only get better. D. Sharon Grant, Chicago's former School Board president, was convicted in July 1995 for tax evasion. Her director of facilities was convicted for extorting $330,000 from contractors. Buildings were overcrowded and falling apart. Rarely did a summer pass without a teachers' strike or threat of a walkout, invariably followed by a surrender by the city, resulting in higher wages or more permissive work rules. Teachers' salaries average $45,508 for a 39-week work year.

It helps that Vallas comes from outside the educational establishment. Unlike other big city school bosses, like New York's Rudy Crew or San Francisco's Waldemar Rojas, Paul Vallas is no educrat.

Before becoming chief of the Chicago system in 1995, he was budget director for Mayor Richard Daley, and before that was Illinois' top budget analyst.

Vallas got the job three years ago after the Republican-controlled Illinois state legislature in Springfield passed a sweeping reform bill that gave Mayor Daley effective control of the Chicago public school system. The mayor bagged the old school board of 15 political hacks, selected in a citywide nomination process, in favor of a 5-man board of mayoral appointees. It was to be headed by Gery Chico, 41, a powerful lawyer who had been Daley's chief of staff. Impressed with Vallas'? ability to crunch numbers and cut through red tape, Chico asked Mayor Daley to appoint Vallas to run the school system day-to-day.

Right from the start, Vallas showed that he knew how to use politics and publicity to get done what needed to be done. Vallas had his operations chief call a press conference at a warehouse filled with $250,000 worth of chairs, copying machines, vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, air conditioners and nine upright pianos. All had gathered dust while schools were supposed to be short of supplies. The newspapers ate it up.

With a $2.7 billion school budget, the city was facing a $150 million deficit for 1995-96 and a projected $1.3 billion hole by 1999. The old board, like most educracies, had always solved that problem by simply hiking property taxes.

Vallas knew he had to tackle the unions, but he started small, using his powers under the new state law to privatize custodial services.

Wiped out were 800 building trades jobs paying on average $44,000 a year. Privatizing saved about $35 million a year. Renegotiating a wildly inflated health insurance contract signed by Chico's predecessor saved the city $115 million over four years.

With a balanced budget, the board was able to sell bonds in 1996 for the first time in nearly 20 years. While districts in Detroit and New York scramble for funds for new school buildings and roofs, Chicago is adding 1,600 classrooms. "It really makes a big difference when the kids walk into a building that looks like it's well taken care of," says Ann Shorey, principal of the Louisa May Alcott Elementary School, where a new playground, roof and windows have been put in.

Much of what Vallas is doing, other cities would dearly love to accomplish -- but they lack the will and authority to fight destructive union practices. Vallas and Chico have a powerful negotiating position.

The new state law, passed in 1995 over the objections of almost every Democratic state legislator, came with an 18-month no-strike clause and made it easier to fire bad or burned-out teachers.

Vallas showed he meant business when he threw out the custodians in defiance of the building trades union. Somewhat intimidated, the teachers were prepared for the worst. Vallas surprised them by offering a 14% raise over four years. They took it. That summer there were none of the usual blusters about a strike.

"People tell me I'm getting things done through fear," Vallas says, admitting to a reporter that he relishes his tough-guy image. "But if the numbers keep going up, we'll bottle it and sell it."

Working fast, Vallas moved on to the toughest part of his job -- making public schools accountable for their results rather than blaming poor test scores on parents or society. Vallas put 109 poorly performing schools on academic probation at the start of the 1996-97 school year.

What this means is that these schools get extra money and the help of outside consultants to craft an improvement plan. Call it the educational version of Chapter 11.

At Roald Amundsen High School in the city's Ravenswood neighborhood, Principal Edward Klunk began working with a team of curriculum consultants Vallas imported from Northeastern Illinois University. They prodded Amundsen's teachers to come up with reading instruction strategies. Students started using stick-on notes and highlighters to flag key points in textbooks. Or they would draw pictures of a chapter's main idea to reinforce their reading comprehension.

English teacher Thomas Hunter had his students draw the urn while teaching John Keats' "Ode on a Grecian Urn."

"If it's not all on there, they haven't read the poem," he explains. Teachers meet every Monday to share ideas and success stories. Some even come in to work on Saturdays.

Amundsen was the only high school to get itself off probation last year. The other Chapter 11 schools are feeling the pressure. Schools that fail to show substantial academic improvement Vallas simply "reconstitutes" by ousting principals and teachers. Last summer he did this to 7 schools, removing 5 of the 7 principals and nearly 200 teachers.

These teachers continue to be paid for ten months, but must reapply and reinterview if they want another public school teaching job. So far 65 teachers are still out of a job. In the ten years prior to that only a handful of tenured teachers had ever been fired for incompetence in the state of Illinois.

Both New York City and Philadelphia have appointed crusading school superintendents, but neither has achieved anything like the results Vallas has. Philadelphia Superintendent David Hornbeck tried to take over two schools, but the teachers' union blocked his effort. No teachers have been laid off as a result of reconstitution in either New York or Philadelphia. Says Christopher Shawn Carr, a college-bound senior at Chicago's reconstituted Orr Community Academy: "I see teachers caring more about students learning. Last year more [teachers] were there just to get paid."

Vallas has even tackled the pernicious practice of social promotion -- moving kids up each year whether they deserve it or not -- for the sake of self-esteem. High school principals complained they were being saddled with ninth graders reading at sixth- or seventh-grade levels.

In March 1996 Vallas ended social promotion. Those who didn't pass year-end tests had to go to summer school. Last summer nearly 41,000 third, sixth, eighth and ninth graders went for intensive instruction in reading and math, at a cost of $34 million. Half passed the retest. Of the remaining students, 1,000 will go to transition centers with smaller class sizes and increased individual attention. The rest will repeat the year.

Later this year Vallas plans to move the Board of Education headquarters from a monstrous 1.9 million-square-foot former Army supply depot to smaller quarters closer to downtown.

His dream plan for the old building is symbolic as well as practical: He wants to have a teacher plunge a detonator that will blow up the building, reducing it to rubble.

BUSINESS WEEK STORY EXPOSING THE FRAUDS OF 'CHAINSAW AL' DUNLAP

HOW AL DUNLAP SELF-DESTRUCTED

The inside story of what drove Sunbeam's board to act

On June 9, Sunbeam (SOC) Chairman and CEO Albert J. Dunlap stormed out of a board meeting in Rockefeller Center, leaving a conference room filled with puzzled and incredulous directors. Most of them thought the once celebrated champion of downsizing, under mounting pressure, was becoming unglued. One director, say three participants, openly expressed concerns about Dunlap's emotional state.

Demanding their support, Dunlap, 60, had just told his board that billionaire financier Ronald O. Perelman and others were engaged in a conspiracy to drive the small-appliance maker's already slumping stock down further so they could buy Sunbeam Corp. on the cheap. He suggested that if Michael Price, an influential mutual-fund manager who had recruited Dunlap nearly two years earlier, really backed him, he would buy out Perelman's $280 million stake.

Why Perelman, one of Sunbeam's largest investors, who owns 14% of the company, would do anything to diminish his investment, he could not explain. ''We can't fight a battle on two fronts,'' said Dunlap, according to several directors. ''Either we get the support we should have or [chief financial officer] Russ and I are prepared to go.... Just pay us.''

NEAR TEARS. ''Al, we don't know what you're talking about,'' retorted Director William T. Rutter, a banker patched into the meeting by phone from Florida, according to several participants. ''We're supportive of both of you.''

So were all the other four outside directors. Again and again they assured Dunlap and his close ally, Russell A. Kersh, of their support. Kersh, say several directors, seemed near tears. ''I don't know what Al thought or what was going through his head,'' says Peter A. Langerman, Price's board representative. ''But I didn't hear anything from Perelman, and Price was still behind him.''

In four days, however, the directors voted to fire the man who has made a phenomenal business career out of firing others. Rarely does anyone express joy at another's misfortune, but Dunlap's ouster elicited unrestrained glee from many quarters. Former employees who had been victims of his legendary chainsaw nearly danced in the streets of Coshatta, La., where Dunlap shuttered a plant. Says David M. Friedson, CEO of Windmere-Durable Holdings Inc.(WND), a competitor of Sunbeam: ''He is the logical extreme of an executive who has no values, no honor, no loyalty, and no ethics. And yet he was held up as a corporate god in our culture. It greatly bothered me.'' Other chief executives, many of whom considered him an extremist, agreed that Dunlap's demise was a welcome relief.

Even members of his own family--long estranged from the man--seemed ebullient. Upon hearing the news of his father's sacking on CNBC at 6:20 a.m. in Seattle, Troy Dunlap chortled. ''I laughed like hell,'' says Dunlap's 35-year-old son and only child. ''I'm glad he fell on his ass. I told him Sunbeam would be his Dunkirk.'' Dunlap's sister, Denise, his only sibling, heard the news from a friend in New Jersey. Her only thought: ''He got exactly what he deserved.''

Sunbeam's stock, meanwhile, has plummeted from a high of 52 in early March to a low of 8 13/16 on June 22, below the level it traded when Sunbeam announced Dunlap's hiring in mid-1996. One analyst, Nicholas P. Heymann of Prudential Securities Inc., said the stock was trading ''more on vindictive emotions than rational analysis.''

How could a single businessman arouse such emotions? In little more than four years, Al Dunlap made more than $100 million, ran two well-known public corporations, wrote a best-selling, vainglorious autobiography, and axed some 18,000 employees. Dunlap, of course, was hardly the only chieftain to order hefty workforce cuts or to say that the only stakeholders in a public corporation are its investors. But by eagerly seeking publicity to expound his simple philosophy, he emerged as the poster boy for ''shareholder wealth.'' Since his departure from Sunbeam, Dunlap has been uncharacteristically silent. Along with his attorney, Christopher J. Sues, and CFO Kersh, he has not responded to repeated requests to be interviewed for this story.

To investors who made millions by following him, Dunlap was, if not a god, certainly a savior. He parachuted into poorly performing companies and made tough decisions that quickly brought shareholders sizable profits. ''We're all seduced by the possibility of big wins,'' says PaineWebber Inc. analyst Andrew Shore, who follows Sunbeam. After meeting Dunlap in mid-1996, Shore immediately put out a buy on the stock. ''I didn't necessarily like him or trust him,'' he recalls, ''but I thought my clients could make money on him. I knew they just had to get out at the right time.''

But if Chainsaw Al's rise to prominence was a '90s version of Barbarians at the Gate, his sudden demise may signal the beginnings of a more tempered era. With much of Corporate America considerably leaner and labor markets tight, taking a two-by-four to a problem is no longer perceived as a viable solution. ''The need to do major downsizing is over. The opportunities to pick that kind of low-hanging fruit aren't as prevalent, and the second picking often requires different skills and methods than a Dunlap is known for,'' says Edward E. Lawler, a management professor at the University of Southern California. ''Clearly, his era has come and is going.''

DEMOLITION EXPERT. It was a supremely confident and triumphant Dunlap who arrived at the troubled appliance maker in July, 1996. Six months earlier, he had successfully completed the sale of Scott Paper Co. Wall Street lustily cheered his arrival at the $1.2 billion maker of electric blankets and outdoor grills. Sunbeam's stock surged nearly 50%, to 18 5/8, the day after his July 18 appointment. Less than four months later, Dunlap lived up to his reputation as a corporate demolition expert. He announced the shutdown or sale of two-thirds of Sunbeam's 18 plants and the elimination of half its 12,000 employees.

Predictably, Wall Street applauded Dunlap's actions, reporters wrote favorably of his exploits, and the stock zoomed up. It traveled so far in that direction, in fact, that it foiled Dunlap's initial strategy to sell the company. Although he hired investment banker Morgan Stanley Dean Witter & Co.(MWD) to seek a buyer last October, no one would pay that large a premium (the stock had risen by 284% since July, 1996, to over 48). That forced Dunlap to consider another alternative: to scour the market for companies to buy. In early March, Dunlap bought not one but three companies in one fell swoop: Coleman, the camping-gear maker, from Perelman in a stock-and-cash deal; First Alert smoke alarms, and Signature Brands, the maker of Mr. Coffee.

Dunlap's most devoted fans, of course, resided on Wall Street. But Shore of PaineWebber wasn't one of them. Trained by the legendary Perrin Long, who made him come to work by 7 a.m. and labor over weekends, Shore, 37, had been following the household products and cosmetics industries for a decade when Dunlap arrived at Sunbeam.

When the stock spiked when Dunlap was appointed, Shore thought the reaction irrational and said so. His candor hardly pleased Dunlap, who would claim that Shore was biased against him because PaineWebber didn't get Sunbeam's investment banking business. (Shore denies that charge.) Still, the analyst jumped on the bandwagon himself, knowing Chainsaw Al could make his clients money. With each new earnings report, however, he carefully dissected Sunbeam's ever-improving results.

It didn't take long for alarm bells to sound. After the company reported its results in the second quarter of 1997, Shore says he began ''getting pangs in my stomach.'' The numbers showed that Dunlap was building what Shore considered abnormally high inventory levels and accounts receivable. His trade contacts confirmed his suspicions that Sunbeam was giving lucrative terms to dealers to ship products aggressively.

''BILL AND HOLD.'' ''I said to myself: 'Let's play the game a little longer,''' remembers Shore. ''No one [had] soured on him yet. Very few picked it up, only the smart shorts at the hedge funds. I thought it would take several more quarters to play out.'' Shore alerted his clients to the warning signs but continued to recommend the stock because he thought investors would keep bidding it up.

He was right. Sunbeam's shares kept climbing, even though the company's third-quarter results created even greater cause for concern. Shore noted in one of his reports that there were massive increases in sales of electric blankets, usually a fourth-quarter phenomenon. Then, in the fourth quarter of 1997, he was alarmed by enormous increases in sales of grills, at a time when virtually no one buys those products. Still, Shore says, ''I didn't think the story was over just yet. The market hadn't caught it.''

Although unknown at the time, Dunlap was aggressively trying to push out more and more product. As the company later acknowledged, he began to engage in so-called ''bill and hold'' deals with retailers in which Sunbeam products were purchased at large discounts and then held at third-party warehouses for delivery later. By booking these sales before the goods were delivered, Dunlap helped boost Sunbeam's revenues by 18% in 1997 alone. In effect, he was shifting sales from future quarters to current ones. The approach was not illegal, but the extraordinary volume made it unusual. Dunlap defended the practice, saying that it was an effort to extend the selling season and better meet surges in demand. Sunbeam's auditors, Arthur Andersen & Co., later insisted it met accounting standards.

On Mar. 19, Sunbeam acknowledged that first-quarter results would be below analysts' estimates. Two weeks later, on Apr. 2, Shore heard more disturbing news: Donald R. Uzzi, Sunbeam's well-regarded executive vice-president for worldwide consumer products, had been fired by Dunlap. Not able to reach Uzzi or Dunlap for confirmation, Shore sought out investor-relations chief Richard Goudis, only to discover that he had quit. Finally, the analyst thought, it was time to advise his clients to get out of the stock. He frantically downgraded the stock on Apr. 3 at 9:00 a.m., and it quickly fell by 4 points. Some two hours later, Sunbeam disclosed that it would post a first-quarter loss. By day's end, the stock fell 25%, to 34 3/8, and shareholders soon filed lawsuits charging deception, an accusation that Sunbeam dismisses as ''meritless.''

Undaunted, Dunlap swiftly hatched a plan for a comeback. On May 11, before 200 major investors and Wall Street analysts--including Shore--he promised that the company would rebound from its dismal first-quarter loss of $44.6 million. Dunlap conceded that he had taken his ''eye off the ball'' to focus on the trio of acquisitions he made in March and had allowed underlings to offer ''stupid, low-margin deals'' on outdoor cooking grills. But he insisted that it would ''never happen again,'' and that Sunbeam would post earnings of 5 cents to 10 cents a share in the second quarter and $1 a share for the full year.

Not everyone felt reassured, least of all Shore, who had several contentious exchanges with Dunlap at the meeting. Afterward, as Shore was heading out the door, Dunlap made a beeline for him. ''I saw this wild man coming forward,'' recalls Shore. ''He grabbed me by my left shoulder, put his hand over his mouth and near my left ear and said: 'You son of a bitch. If you want to come after me, I'll come after you twice as hard.''' One Sunbeam adviser corroborates Shore's account.

Dunlap's performance at that meeting--including his announcement of another 5,100 layoffs at Sunbeam and the newly acquired companies--didn't prevent the stock from dropping further. Nor did Dunlap's speech stop news reports about what Shore had discovered nearly nine months earlier: that Sunbeam was engaged in highly aggressive sales tactics and accounting practices that inflated revenues and profits. The most scathing analysis, in Barron's, alleged that Dunlap employed $120 million of ''artificial profit boosters'' last year when the company reported $109.4 million in net income.

Dunlap was so concerned about the effects of the story that he called an impromptu board meeting for June 9 to rebut the charges. He arrived for the session at 4 p.m. Besides the five outside board members, there was a bevy of external advisers, including lawyers, public relations consultants, and the company's accountant from Arthur Andersen. Dunlap, recalls one participant, ''seemed strangely subdued and quiet.''

Kersh and Controller Robert J. Gluck led the board through the charges, denying virtually all of them. The Arthur Andersen partner assured the board that the company's 1997 numbers were in compliance with accounting standards and firmly stood by the firm's audit of Sunbeam's books. The directors discussed a range of alternatives to deal with the story, from the filing of a libel suit to issuing a detailed letter of corrections to its shareholders.

The discussion was drifting when it was decided simply to draft a point-by-point rebuttal for the company's bankers and directors. Suddenly, Director Charles M. Elson, a Stetson University law professor and friend of Dunlap's, asked how the company's second quarter was shaping up. The following exchange then occurred, according to four of those who were present.

''Sales are a little soft,'' said Kersh.

''Well, do you think you're going to make the numbers?'' asked Elson.

''It's going to be tough,'' replied Kersh.

''This is a transition year,'' Dunlap responded. ''You've got to stop worrying about specific numbers. We're trying to prepare for 1999.''

Dunlap then said he wanted to discuss something privately with the board. All the outside advisers departed, leaving only Dunlap, Kersh, and the five directors. Over the next 20 minutes, Dunlap told the board that either he needed the right level of support or he was prepared to go.

''If you really want me and Russ to go, then let's settle up the contract and we'll go,'' Dunlap said, according to several board members. ''I have a document in my briefcase that we can go over and get it done.''

The board was stunned. Dunlap told them he believed that Perelman was orchestrating a torrent of bad media coverage so he could buy the company at a bargain. Some of the directors said later that they thought Dunlap was becoming emotionally distraught. They did not believe that Perelman, who declined comment, would undermine himself that way. His ownership stake enabled him to affect change more directly.

SUSPICIONS. Shortly after the exchange, Dunlap and Kersh got up and marched out of the room. After allowing the pair enough time to reach the elevator bank, Howard G. Kristol broke the silence. Of all of them, he had known Dunlap the longest. For more than 20 years, Kristol had been his personal attorney. He had drafted Dunlap's employment pacts at Scott Paper and Sunbeam.

''That is complete bullshit,'' Kristol blurted out, according to several directors. ''Just bullshit.''

Everyone in the room agreed. No one had uttered any doubt about Dunlap's ability to lead the company. No one thought he had cooked the books. So why would he bring up the possibility of resigning?

''I don't know about you, but what I'm clearly hearing is that Al and Russ want out,'' Kristol recalls saying. The others concurred. The timing could not have been worse. Although the company was in crisis, Dunlap was about to go to London to give a speech and promote his book, while Kersh was going off on vacation in Ohio. They were concerned that Dunlap lacked the resolve to continue in the job, was unaware of the deteriorating results, or worst of all, was being less than candid. ''We all sat there feeling like we were going to throw up,'' says Elson. ''It was horrible.''

Dunlap's strange behavior led director Faith Whittlesey to openly suggest that perhaps the CEO was suffering from emotional distress, say three directors. She was not the first to wonder if he had lost perspective in the wake of the barrage of hostile media coverage. Some of his closest associates thought he had become oddly subdued and introspective--quite a departure from the volatile and voluble man they knew.

Before leaving the conference room, the directors exchanged personal phone numbers so they could stay in close touch. Several, particularly Langerman, agreed to dig more deeply into the company and question other Sunbeam executives over the next few days. When the session finally broke up around 8 p.m., Elson was so distraught that he spent the next three hours wandering the streets of Manhattan.

Over the following two days, Langer-man did considerable homework. Unbeknownst to Dunlap, he called several Sunbeam insiders, including three top operating executives, Lee Griffith, Frank J. Feraco, and Franz Schmid. But the most important break came when he spoke with Sunbeam's Executive Vice-President David C. Fannin.

Fannin, 52, didn't fit the Dunlap mold. Unlike his tempestuous, self-promoting boss, Fannin is unassuming and mild-mannered. The Kentucky-born lawyer had worked at a blue-chip law firm in Louisville for nearly 20 years when a client recruited him to Sunbeam in 1993 as interim general counsel. Of Sunbeam's top dozen senior executives, he would be the only survivor, someone who viewed himself as a moderating influence on his mercurial boss.

IN CRISIS. Dunlap not only brought Fannin into his inner circle, he handsomely rewarded the lawyer for his loyalty and commitment. In February, for example, Dunlap handed him a new three-year contract that raised his base salary by 90%, to $595,000, along with a huge stock option grant on 750,000 shares, now underwater. What Dunlap failed to notice, however, was that Fannin had become demoralized by what he saw at Sunbeam. It was hard to really like Dunlap, with his hair-trigger temper. Many times Fannin considered quitting. ''But it was like being in an abusive relationship,'' he says. ''You just didn't know how to get out of it.''

Fannin, however, had now reached the breaking point. Although Kersh told the board the second quarter would be soft, a week earlier Fannin had been at a Sunbeam meeting at which considerable concern was raised that the results would be far below Dunlap's May 11th forecast. At that session, the numbers coming in showed that revenues were falling by as much as $60 million in the quarter. In last year's second quarter, Sunbeam's sales were $287.6 million.

When Langerman called Fannin on Wednesday morning at his office, Fannin was ready to reveal what he knew. ''I was totally disillusioned,'' he said. ''I felt this was not something I wanted to be involved in any further.'' Later that night, while at home, he told Langerman that the numbers were much worse than soft, and that the company was in crisis.

Meanwhile, Fannin did some interviewing of his own from Wednesday to Friday of that week. He met with Gluck, the controller, a finance analyst who had been a pre-Dunlap holdover, and asked pointed questions about the quality of the 1997 earnings. ''I didn't like the answers I got,'' recalls Fannin. ''He said: 'Look, as much as possible, we tried to do things in accordance with GAAP, (generally accepted accounting principles), but everything has been pushed to the limit.' There was no smoking gun, but taken as a whole, this was not a sustainable situation.'' Gluck did not respond to requests to be interviewed.

Langerman called his fellow directors and asked them to come to an emergency meeting in Kristol's Rockefeller Center offices on Saturday morning. Fannin agreed to come to report on what he had found. ''Had he not come forward,'' says Elson, ''it would have been extraordinarily difficult for us to act. He was the quiet hero. He really put his neck out.''

On Saturday morning, June 13, Sunbeam's outside directors solemnly gathered around the same rectangular conference room table where only four days earlier they had had their odd meeting with Dunlap and Kersh. A box of Krispy Kreme doughnuts served as breakfast. Four of the directors were there, along with Fannin and a pair of lawyers from Skadden Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. Director Rutter was on the telephone from Captiva Island, Fla., where he was on vacation with his family.

The directors all agreed Dunlap had to go. With the exception of Langerman, the directors were Dunlap's friends. But they also felt betrayed by him, misled about the company's financial condition, its second-quarter earnings, and its yearly numbers as well, they later said. ''We lost our confidence in him and the ability to sustain things was questionable,'' says Rutter.

By noon, Skadden Arps lawyer Blaine V. ''Finn'' Fogg carefully scripted the words that Langerman would say to Dunlap when they placed the conference call. ''All the outside directors have considered the options you presented to us last Tuesday and have decided that your departure from the company is necessary,'' Langerman read aloud.

Elson then made the motion to dump Dunlap, but he couldn't bring himself to read it. ''It felt too cruel,'' he recalls. ''We had gone back a long way, and I just couldn't do it.''

So after Elson put forth the motion, it was quickly seconded by Kristol and dryly read by Fannin. The outside directors passed it unanimously.

NO EXPLANATION. ''I think I'm entitled to an explanation,'' Dunlap said finally, according to several participants in the meeting.

He wouldn't get one. Instead, Langerman told him to contact the board's lawyer. Kristol adjourned the meeting shortly after. Three days later, during a telephone session, Kersh was fired as well.

The day after Dunlap was axed, the board met again in Skadden Arps' offices. It named as the new chief executive Jerry W. Levin, a longtime aide to Perelman and former CEO of Coleman, which now comprises about 40% of Sunbeam's revenues. Langerman, who agreed to serve as nonexecutive chairman, had called Perelman on Saturday afternoon to ask for help. Levin was on his way to see a movie that evening when Perelman asked if he would be interested in taking over.

Now, Levin has to sort out the mess. Not only is Sunbeam expected to report another loss in the second quarter and possibly for the year, but the company is also under an informal probe by the Securities & Exchange Commission. It is also expected to be in technical default on a $1.7 billion bank loan by June 30. Already, Levin is expected to win a reprieve from the banks, but it will take some time to turn Sunbeam around.

Dunlap still has followers who predict a comeback, though headhunters say it's unlikely he'll ever get another chance to run a major company. In the end, Al Dunlap, the kid from Hoboken, N.J., the son of a union steward, fell on his own weapon, the sword of shareholder value. ''Dunlap got thrown out not because the board said his way was the wrong way to run a company,'' notes Peter D. Cappelli, chairman of the Wharton School's management department. ''He was fired because he couldn't make his own numbers.''

By John A. Byrne in New York TABLE: Chainsaw Al's Waterloo

CHART: Thrills and Chills

?

Comments:

By: Bob Busch

Chainsaw Paul's road back to Springfield

In a nightmare scenario Paul Vallas realizes that he is no Democrat just like Ronald Regan

did in the early 60's.

He gets himself nominated for Governor. if you think this is crazy, remember he has great name recognition. All it would take is a Democratic bloodbath in the primary and a phoney, but viable, Black independent candidate.

By: John Kugler

Vallas and the Destruction of America!

As Philadelphia’s superintendent, Paul Vallas, had been in Chicago prior to Philadelphia. In Chicago, he had enacted similar "reforms" as those he put in Philadelphia.

When is the public going to wake up that it is not their fault that education is destroying our youth? It is a planned and coordinated ruling class objective to create a subservient under class.

Bankrupt in Philadelphia: Could This Happen to Your School District?

http://www.takepart.com/article/2013/07/08/philadelphia-school-district-financial-crisis