MEDIA WATCH: GQ gets it, Chicago's 'news' organizations don't... How charter schools kick out feisty kids, leaving the families to send the kids back to public schools or home school

By the end of February, 2011, as the second semester of the 2010 - 2011 Chicago Public Schools school year begins, one of Chicago's dirtiest little secrets, covered up by Chicago's corporate media, will be showing up across the city at dozens of elementary and high schools. Once the 20th day of second semester passes, Chicago's vaunted charter schools will be "counseling out" (mind you: not kicking out) their bad students, who will then either disappear (many never get anywhere else) or show up at already stressed neighborhood elementary and high schools.

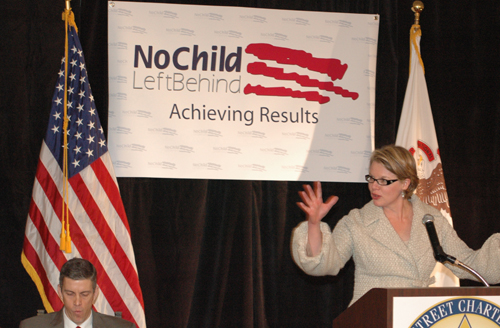

While Chicago's charter schools were pushing out their low scoring and at risk students on a regular basis, as early as the middle years of the first decade of the 21st Century, Chicago public school officials were using every opportunity to work with U.S. Department of Education officials during the Bush administration to promote charters and denigrate the regular public schools. On January 25, 2007, Chicago Public Schools Chief Executive Officer Arne Duncan (above left) and Chicago Board of Education President Rufus Williams arranged for then U.S. Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings (above at podium) to do a major visit to Chicago celebrating the supposed success of the No Child Left Behind law. Instead of doing the event at a real public school like Whitney Young High School, which was a mile from the media event (above), Duncan and Williams chose the Noble Street Charter High School for the event. It gave additional corporate support to Noble Street, while furthering the bipartisan corporate charter school agenda, despite the fact that Chicago's charter schools, led by the example of Nobel Street's Michael Milkie, had been dumping their riskiest students back into the public schools regularly, so that the "results" they could claim to have achieved were based on the skimming out of those who would bring "down" their numbers. Substance photo by George N. Schmidt.The scam has been going on for years, pioneered by former Wells High School teacher Michael Milkie, who has headed the Noble Street Network of charter schools since leaving Wells High School nine years ago. Beginning in the second year of Noble Street's much-praised reign, Milkie discovered that he could keep his numbers (mostly test scores, and claims of a low dropout rate) very very low by simply sending the kids least likely to succeed back to the school he came from (amid lurid denunciations of the uncreative and bureaucratic wasteland that is the unionized Chicago public school system).

While Chicago's charter schools were pushing out their low scoring and at risk students on a regular basis, as early as the middle years of the first decade of the 21st Century, Chicago public school officials were using every opportunity to work with U.S. Department of Education officials during the Bush administration to promote charters and denigrate the regular public schools. On January 25, 2007, Chicago Public Schools Chief Executive Officer Arne Duncan (above left) and Chicago Board of Education President Rufus Williams arranged for then U.S. Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings (above at podium) to do a major visit to Chicago celebrating the supposed success of the No Child Left Behind law. Instead of doing the event at a real public school like Whitney Young High School, which was a mile from the media event (above), Duncan and Williams chose the Noble Street Charter High School for the event. It gave additional corporate support to Noble Street, while furthering the bipartisan corporate charter school agenda, despite the fact that Chicago's charter schools, led by the example of Nobel Street's Michael Milkie, had been dumping their riskiest students back into the public schools regularly, so that the "results" they could claim to have achieved were based on the skimming out of those who would bring "down" their numbers. Substance photo by George N. Schmidt.The scam has been going on for years, pioneered by former Wells High School teacher Michael Milkie, who has headed the Noble Street Network of charter schools since leaving Wells High School nine years ago. Beginning in the second year of Noble Street's much-praised reign, Milkie discovered that he could keep his numbers (mostly test scores, and claims of a low dropout rate) very very low by simply sending the kids least likely to succeed back to the school he came from (amid lurid denunciations of the uncreative and bureaucratic wasteland that is the unionized Chicago public school system).

Beginning in Chicago and a few other cities (KIPP discovered the same trick in California in the early years of the 21st Century), and slowly advancing since, the practice of keeping kids in your charter school until the money rolls in (following the census of students that takes place on the 20th day of each semester) and then dumping them out (often to nowhere, or to an overburdened local real public school) has become the standard for charter schools across the USA. It is ignored by Arne Duncan as U.S. Secretary of Education just as it was ignored by Arne Duncan when he was "Chief Executive Officer" of Chicago's public schools from 2001 through 2008, the years that Noble Street and others were perfecting the scam.

Of course, Chicago's corporate media, led by the charter school cheerleaders in the "news" departments of the Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Tribune, ignore the scam, even when it is brought to their attention by desperate parents and schoolless children. In the Orwellian world of corporate "school reform" — CHARTER GOOD. PUBLIC BAD — could be the chant of the animals in the Chicago version of Animal Farm.

By January 25, 2007, Michael Milkie had been running the Noble Street Charter High School, which was becoming the Noble Network of charter high schools, to this date highly touted by corporate school reformers and corporate media in Chicago. Milkie, a former Wells High School teacher, regularly sent his students back to Wells when they "failed" by Noble Street's complex rules, and as his network expanded dramatically with major corporate support, more and more students who had made Noble Street their "choice" found out that Noble Street had the right to "dechoice" them. Substance photo by George N. Schmidt.So it was with some surprise that we discovered that, of all publications, GQ was exposing the scam, not in Chicago, where it is carried out on an industrial scale, but on the smallest possible scale in Austin, Texas, where a parent narrates the saga of how one sanctimonious charter school kicked his son out — of kindergarten!

By January 25, 2007, Michael Milkie had been running the Noble Street Charter High School, which was becoming the Noble Network of charter high schools, to this date highly touted by corporate school reformers and corporate media in Chicago. Milkie, a former Wells High School teacher, regularly sent his students back to Wells when they "failed" by Noble Street's complex rules, and as his network expanded dramatically with major corporate support, more and more students who had made Noble Street their "choice" found out that Noble Street had the right to "dechoice" them. Substance photo by George N. Schmidt.So it was with some surprise that we discovered that, of all publications, GQ was exposing the scam, not in Chicago, where it is carried out on an industrial scale, but on the smallest possible scale in Austin, Texas, where a parent narrates the saga of how one sanctimonious charter school kicked his son out — of kindergarten!

But rather than carry on about Chicago, which Substance will be reporting on in detail in the coming months, here is what GQ reports in January 2011:

Kicked Out of Kindergarten, Part 1. The true story of what happens when an unemployed dad and his rambunctious six-year-old son are forced to conduct an involuntary experiment in homeschooling. Introducing a new five-part series about fatherhood and other catastrophes, BY STEVE WILSON, January 2011

My son's hippy charter school did not do Christmas. Instead, the administrators created an artificial, substitute holiday called the Labyrinth Celebration, and they took it very seriously. So seriously that the teachers didn't think twice about marching dozens of children—and me—outside in howling winds and numbing cold for an hour to practice a stupid song about a shiny lantern.

The dishonest narrative about Chicago's charter schools was impossible to sustain without the support of Chicago's corporate media. Above, (then) reporter Kate Grossman of the Chicago Sun-Times (background, left) takes dictation from (then) CPS CEO Arne Duncan, while (then) U.S. Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings enters the room where CPS was hosting Spellings's celebration of the anniversary of No Child Left Behind and its supposed successes. Substance photo by George N. Schmidt."I don't know the words," my son Wilson confessed through chattering teeth. He'd only paid sporadic attention in music class.

The dishonest narrative about Chicago's charter schools was impossible to sustain without the support of Chicago's corporate media. Above, (then) reporter Kate Grossman of the Chicago Sun-Times (background, left) takes dictation from (then) CPS CEO Arne Duncan, while (then) U.S. Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings enters the room where CPS was hosting Spellings's celebration of the anniversary of No Child Left Behind and its supposed successes. Substance photo by George N. Schmidt."I don't know the words," my son Wilson confessed through chattering teeth. He'd only paid sporadic attention in music class.

"Let's fake it," I said.

As the shivering kindergarteners around us mumbled their way through the song, Wilson and I lip synced, cracking each other up with exaggerated faces. The humor wore off after we finished the song and waited, and waited, while the organizers dithered over where the other K-6 kids should stand and sing.

Anita* [name changed for this article], Wilson's teacher, fought a losing battle to keep her batch of five-year-olds standing still in the arctic freeze. But back at the end of the line, I let Wilson spazz-dance around and jump off a short garden wall. "Paratrooper!" he screamed. At least he was keeping warm. I only gave him a token warning about crashing into people after he joined hands with a girl named Daisy and spun her in circles. Wilson and Daisy both laughed as they fell to the ground. But Anita wasn't amused. "Hey!" she shouted at me. "Would you keep them under control?"

All of the members of the Chicago Board of Education went out of their way to promote charter schools and denigrate the public schools as Chicago charters expanded exponentially during the 21st Century. Above, Chicago Board of Education President Rufus Williams (right at podium) helped organize and execute the promotional for Michael Milkie's Noble Street Charter High School on January 25, 2007, when then U.S. Secretary of Education came to Chicago to tout No Child Left Behind and celebrate its anniversary. Substance photo by George N. Schmidt. When I agreed to chaperone Wilson at his school a few weeks earlier, I hadn't signed on to be scolded by a kindergarten teacher. Not that I really minded—she was just cold and overwhelmed. And it's not like I had much dignity left anyway. Getting leg cramps at Rug Time and being jostled by kids at the pint-size urinals during Bathroom Break will do that to you. Actually, my entire experience as a parent had done that to me. Years of playing stay-at-home dad in family-friendly Austin for two "spirited" boys had burned me out. As much as I loved my kids, I'd counted the days until Wilson started school and his younger brother, Oliver, could start daycare. I had a cushy part-time job editing an alumni magazine for a small university nobody cared about, but I hadn't had any real time to myself for years. Finally I could get my life back. Do more freelance writing. Read an entire book. Use the bathroom without interruption.

All of the members of the Chicago Board of Education went out of their way to promote charter schools and denigrate the public schools as Chicago charters expanded exponentially during the 21st Century. Above, Chicago Board of Education President Rufus Williams (right at podium) helped organize and execute the promotional for Michael Milkie's Noble Street Charter High School on January 25, 2007, when then U.S. Secretary of Education came to Chicago to tout No Child Left Behind and celebrate its anniversary. Substance photo by George N. Schmidt. When I agreed to chaperone Wilson at his school a few weeks earlier, I hadn't signed on to be scolded by a kindergarten teacher. Not that I really minded—she was just cold and overwhelmed. And it's not like I had much dignity left anyway. Getting leg cramps at Rug Time and being jostled by kids at the pint-size urinals during Bathroom Break will do that to you. Actually, my entire experience as a parent had done that to me. Years of playing stay-at-home dad in family-friendly Austin for two "spirited" boys had burned me out. As much as I loved my kids, I'd counted the days until Wilson started school and his younger brother, Oliver, could start daycare. I had a cushy part-time job editing an alumni magazine for a small university nobody cared about, but I hadn't had any real time to myself for years. Finally I could get my life back. Do more freelance writing. Read an entire book. Use the bathroom without interruption.

That simple dream vanished when the principal at Wilson's school demanded that I chaperone him all day and every day. "For safety," she said. By this she meant that she wanted some way to stop the other parents from calling to complain about Wilson. Once he started school, our witty, creative, energetic son had begun using his considerable powers for evil. He'd verbally and physically abused most of his classmates, disrupted nearly every class he'd bothered to participate in, and even managed to kick Anita in the head. (His side of the story: she got in the way of his flailing.)

After second guessing everything we'd ever done as parents, my wife Erin and I started to wonder if Wilson's past was catching up with him. We'd adopted him when he was only five months old, but life hadn't been easy for him up until then—he had been abused and then separated from his mother. A therapist we saw told us that early trauma of the kind he had experienced can wire a child's brain to distrust the world. She recommended a fresh injection of close and constant contact with us—attachment therapy for a kid who'd always kept us at arm's length. We figured the chaperoning might help us reconnect.

Besides, I'd just been laid off, so I had the time.

Not long after the class came in from the cold, Anita had a breakdown during a particularly chaotic Choice Time. Wilson wasn't the only troublemaker in her class. She lined up the most rambunctious kids along the wall and shouted at them, then burst into tears. Did I mention this was her first year teaching? I felt horrible for her. Like me, she was in over her head, doing her best in thankless circumstances. Even so, I was glad Wilson didn't witness her freakout; he'd already been sent to the Focus Room for trying to smash a stack of popsicle frames.

We should have had the sense to take Wilson out of school that day. Kindergarten—the new first grade—was like a gulag to him. But what was the alternative? Home school? That was for creationists and refuseniks whose kids turned out to be maladjusted weirdos or annoyingly successful weirdos like that teenager who wrote Eragon, that fantasy book about dragons. Wilson was a great kid, we reasoned, and if we all just kept trying a little longer, he could be a great student, too.

So we stayed, and slowly, things began to turn around. Over the next few weeks Wilson engaged more with his classmates. He began learning how to calm himself down. He didn't even call me "chicken fart" or "garbage butt" in front of everybody quite as often.

One day, Karen, the school's behavior coach, pulled me away from Anita's reading of Charlotte's Web, which had degenerated into a lecture about interruptions. Karen told me Wilson had improved but was using me as a crutch. I agreed wholeheartedly. "I think we're ready for you to pull back how much time you're spending here," she said. Words kept coming out of her mouth, but all I could think about was one word: freedom.

We set up a meeting for later in the week to plan my scaled-back hours. On the way to school the next morning, I brought it up with Wilson.

Me: "I've got good news. You've been doing so well, I won't have to be with you in class as much."

Wilson: [silence]

A few hours after the promotional media event for Chicago charter schools at Noble Street Charter School (anniversary of No Child Left Behind, January 25, 2007), Margaret Spellings and her team moved the banner that had been on display at Noble Street to the offices of the Illinois Business Roundtable and the Civic Committee of the Commercial Club, where Spellings met with Chicago corporate leaders and the members of the Chicago Board of Education in a meeting that was closed to the public and press. Chicago Board of Education member Norman Bobins (right in the above photograph) is the only member of the Chicago Board of Education who has been on the Board since Mayor Daley took control of CPS in July 1995, and he remains on the Board in January 2011. Bobins, who is being paid more than a million dollars in 2010 for serving on a number of corporate boards of directors following his sale of LaSalle Bank to Bank of American and his retirement (he was CEO of LaSalle Bank prior to the sale) is Director Emeritus of the Illinois Business Roundtable. Photo from the Illinois Business Roundtable website.As soon as we got to school, I knew I'd made a mistake telling him so soon. Within the hour he had stabbed a classmate in the hand with a pencil and hurled a chair across the room. He caused such a ruckus in the Focus Room that Karen—the professional voice of calm and reason—shouted at him and sent us home.

A few hours after the promotional media event for Chicago charter schools at Noble Street Charter School (anniversary of No Child Left Behind, January 25, 2007), Margaret Spellings and her team moved the banner that had been on display at Noble Street to the offices of the Illinois Business Roundtable and the Civic Committee of the Commercial Club, where Spellings met with Chicago corporate leaders and the members of the Chicago Board of Education in a meeting that was closed to the public and press. Chicago Board of Education member Norman Bobins (right in the above photograph) is the only member of the Chicago Board of Education who has been on the Board since Mayor Daley took control of CPS in July 1995, and he remains on the Board in January 2011. Bobins, who is being paid more than a million dollars in 2010 for serving on a number of corporate boards of directors following his sale of LaSalle Bank to Bank of American and his retirement (he was CEO of LaSalle Bank prior to the sale) is Director Emeritus of the Illinois Business Roundtable. Photo from the Illinois Business Roundtable website.As soon as we got to school, I knew I'd made a mistake telling him so soon. Within the hour he had stabbed a classmate in the hand with a pencil and hurled a chair across the room. He caused such a ruckus in the Focus Room that Karen—the professional voice of calm and reason—shouted at him and sent us home.

I didn't bother to take Wilson in the next day; we both needed some time off. We hung out at home watching TV and eating the unhealthy food his school didn't allow. Then we went to the indoor YMCA pool, where Wilson launched himself head-first off one foot with his hands behind his back. "It's the No-Hands-One-Foot Dive!" he shouted. We grabbed lunch at Whole Foods, where he learned how to skate on the environmentally unfriendly ice rink they'd refrigerated on the roof. I'd been his prison guard for so long I'd almost forgotten how amazing he could be. "I've had a blast today," I said later in the car. He bugged out his eyes and nodded vigorously, his way of saying "me too."

We showed up after school let out for the meeting Karen that had scheduled before Wilson's big blow-up. But something told me we wouldn't be talking about his improvement anymore. Erin was out of town, so as Wilson ran around on the playground, I faced the principal, Karen and Anita alone.

Karen got to the point. "We don't have the resources to handle him." She said we should re-enroll Wilson in our neighborhood public school, which had a special needs program. The principal blathered on about how they'd tried to help kids like Wilson in the past but it "only made things worse." Anita praised Erin and me for our hard work as parents in a way that sounded patronizing, even though I could tell she felt bad.

Each of them had more to say, but I wasn't really listening. I couldn't get past the part where they'd actually kicked a five-year-old—my five-year-old—out of kindergarten.

*All names have been changed except for members of the author's family.

[Wilson is a freelance writer based in Austin, Texas. Part two of the series, "The Experiment Begins," will be posted on GQ.com on Monday, January 17.]

By: Tonia Mayer

great article

Wow, that explains alot!