MEMORIAL DAY 2016... Donald Duncan, hero, gets his obit in the New York Times — seven years late... Why a new generation needs to learn more about the G.I. Movement that ended the War in Vietnam...

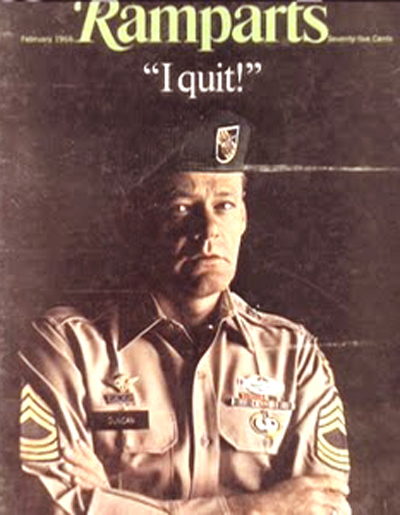

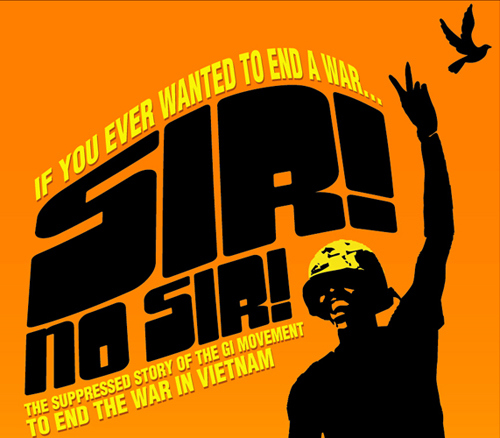

The famous cover of Ramparts magazine that began the anti-war career of former Green Beret Donald Duncan.His square-faced, solid image jumps out first when the film opens. Donald Duncan, a former Army Master Sergeant, a Green Beret, tells his story from Vietnam in the movie, “Sir, No Sir!,” a 2005 film (available from Netflicks) about the rise of the anti-Vietnam War movement inside of the US military.

The famous cover of Ramparts magazine that began the anti-war career of former Green Beret Donald Duncan.His square-faced, solid image jumps out first when the film opens. Donald Duncan, a former Army Master Sergeant, a Green Beret, tells his story from Vietnam in the movie, “Sir, No Sir!,” a 2005 film (available from Netflicks) about the rise of the anti-Vietnam War movement inside of the US military.

Duncan had served in Vietnam. He, like many other vets, had seen (and probably done) some terrible things. “It wasn’t just the the force, the torture, that took place; it was the cynicism about it all that sickened me.”

With that, Duncan got out of the US Army. But he didn’t go silently. He went to the 1960s magazine, Ramparts, and told his story. By March 3, 1966, Duncan was a featured speaker at an anti-war protest in Manhattan. His early and continued opposition to the Vietnam War not only inspired many, but helped those who were opposing the war in working class communities across the USA where patriotism was hard core and in many ways a decent thing.

What Duncan didn’t know at the time — and our history textbooks still don’t tell — is that he was one of the earliest of veterans to publicly protest the US war in Vietnam (and all of Southeast Asia). He didn’t plan to start an anti-war movement — “It was just a personal protest, me getting out” — but he was one of hundreds of thousands of active duty servicemen and women and veterans who turned against the Vietnam war. And he was one of the first.

What we’ve never been told in history classes -- or when America's media talks about holidays like Memorial Day -- is that the US "lost" the war in Vietnam because of two reasons: (1) the total willingness of the Vietnamese to pay any price for their freedom; and (2) because US military personal quit being willing to continue to kill and fight the war.

By 1969, a growing number of soldiers and marines on the ground in Vietnam were basically on strike against the war they had been forced to fight. The longer the war lasted, the more intense those invisible picket lines and the more militant that strike became.

An example? One sad fact from those realities is that the G.I.s who organized against the war from within the war gave American English the verb "frag."

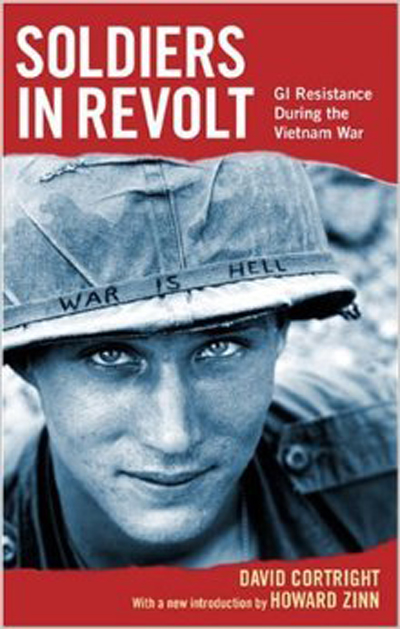

The movie Sir No Sir! is now easily available on line, or by mail order. Although it didn't win an Academy Award, it should have, according to hundreds of thousands of veterans who remember the war against the war that stopped the war from within...the film Sir, No Sir! — which should be in every U.S. history class after about sixth grade — graphically tells the story of this movement by US troops against the war. A few books are also available about that movement, most comprehensively David Cortright's "Soldiers in Revolt", which is now available again (after being out of print) from Haymarket Books.

The movie Sir No Sir! is now easily available on line, or by mail order. Although it didn't win an Academy Award, it should have, according to hundreds of thousands of veterans who remember the war against the war that stopped the war from within...the film Sir, No Sir! — which should be in every U.S. history class after about sixth grade — graphically tells the story of this movement by US troops against the war. A few books are also available about that movement, most comprehensively David Cortright's "Soldiers in Revolt", which is now available again (after being out of print) from Haymarket Books.

What happened to Donald Duncan? After years of activity in the anti-Vietnam war movement, he "disappeared." And died, on March 25, 2009, in Madison, Indiana. His obituary was carried by the local paper, but they didn’t know or ignored his anti-war activities.

The New York Times had been aware of him, although they hadn’t known he had died when they first began searching for him, seeking to prepare an “advanced obituary” before he actually died. Obviously, they found out he had been dead — for seven years! Claiming he was a “newsmaker” and deserving an obit, they finally printed one on May 8, despite the seven-year delay.

The Times did a fairly good job: “But in 1966, well before the Tet offense and the My Lai massacre stirred national discontent, Mr. Duncan was one of the first returning veterans to portray the war as a moral quagmire that had little to do with fighting the spread of Communism, as American leaders were portraying it.”

Further, “In a 1966 cover story for Ramparts … Mr. Duncan told of witnessing murders, torture and other atrocities by American forces in Vietnam in violation of all international laws; of refusing orders at An Khe to kill four enemy prisoners whose hands were tied behind them; and of rapes by South Vietnamese troops that were never reported, let alone punished.”

“The whole thing was a lie,” Mr. Duncan wrote. “We weren’t preserving freedom in South Vietnam. There was no freedom to preserve. To voice opposition to the government meant jail or death. Neutralism was forbidden and punished. Newspapers that didn’t say the right thing were closed down. People are not even free to leave….”

Perhaps after this Memorial Day, and with so many major movements challenging the vast right wing versions of "history" that have been put into place since the 1980s, the studies of U.S. children in schools will include these important truths about the Vietnam War. Not the silly childish tales of draft dodging cowards like Ronald Reagan or Sylvester Stallone, but the facts about men who began their confrontation with the nasty front edge of American imperialism in the Army and Marines itself. If children are to be able to face the future of democracy clearly, the facts about the G.I. and veterans' movements against the Vietnam War need to be in our classes.

The definitive books about the G.I. Movement, Soldiers in Revolt, is now available again, thanks to Haymarket Books.[Kim Scipes is a former Sergeant in the US Marine Corps, who served between 1969-73, and who “turned around” while on active duty, although he stayed in the US for all four years. Scipes, currently an Associate Professor of Sociology at Purdue University Northwest in Westville, IN, just published an edited volume on Building Global Labor Solidarity in a Time of Accelerating Globalization (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016). George N. Schmidt, editor of Substance, became the first Conscientious Objector (I-O) in the Elizabeth New Jersey draft board in 1968, despite the fact that his entire family (including his mother) had been in "the service" during World War II. Schmidt spent seven years doing legal aid, counseling and organizing with GIs as the "G.I. Movement" grew during the late 1960s until the liberation of Saigon in 1975.]

The definitive books about the G.I. Movement, Soldiers in Revolt, is now available again, thanks to Haymarket Books.[Kim Scipes is a former Sergeant in the US Marine Corps, who served between 1969-73, and who “turned around” while on active duty, although he stayed in the US for all four years. Scipes, currently an Associate Professor of Sociology at Purdue University Northwest in Westville, IN, just published an edited volume on Building Global Labor Solidarity in a Time of Accelerating Globalization (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016). George N. Schmidt, editor of Substance, became the first Conscientious Objector (I-O) in the Elizabeth New Jersey draft board in 1968, despite the fact that his entire family (including his mother) had been in "the service" during World War II. Schmidt spent seven years doing legal aid, counseling and organizing with GIs as the "G.I. Movement" grew during the late 1960s until the liberation of Saigon in 1975.]

THE BETTER LATE THAN NEVER NEW YORK TIMES OBITUARY...

Donald W. Duncan, 79, Ex-Green Beret and Early Critic of Vietnam War, Is Dead

By ROBERT D. McFADDEN, New York Times, MAY 6, 2016

Donald W. Duncan, a Green Beret master sergeant who came home from Vietnam a disillusioned hero in 1965 and became a leading early opponent of the war, died in the obscurity of a small Midwestern town seven years ago, an all-but-forgotten soldier. He was 79.

In an age of seeming information ubiquity, the news media will generally recall the lives of noteworthy people when they die. But Mr. Duncan’s death went largely unnoticed outside of Madison, Ind., the Ohio River town where he lived.

His obituary in The Madison Courier said only that Mr. Duncan had once worked for a local nonprofit that helped poor people find jobs. The crucial events of his life — the killings and brutalities of 18 months in Vietnam, the agony of conscience and conversion, and the years of antiwar struggle — had happened long ago and were not mentioned.

Mr. Duncan’s daughters Valerie Casey and Luise Wilson confirmed last week that he died on March 25, 2009, at a Madison nursing home.

In an America torn by protests against the war in the late 1960s and early ’70s, Mr. Duncan was often in the news, although not as prominently as the pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock, the Roman Catholic priests Daniel and Philip Berrigan or the actress Jane Fonda, who was photographed laughing and applauding on an antiaircraft gun in Hanoi. (Daniel Berrigan died on April 30.)

But in 1966, well before the Tet offensive and the My Lai massacre stirred national discontent, Mr. Duncan was one of the first returning veterans to portray the war as a moral quagmire that had little to do with fighting the spread of Communism, as American leaders were portraying it.

Sergeant Duncan, who went to war convinced it was an anti-Communist crusade, ended his Special Forces duty a changed man. A 10-year veteran, he rejected an offer of an officer’s commission and left the Army. Back home, he became a fierce critic of the war, writing articles and a memoir and speaking at rallies across the country with the singer Joan Baez, the writer Norman Mailer and the comedian Dick Gregory.

Photo

Donald W. Duncan in 1970 explaining a legal action alleging that soldiers had been mistreated at Fort Benning in Georgia. Credit Mike Lien/The New York Times

In a 1966 cover article for Ramparts, a radicalized Roman Catholic political and literary journal, Mr. Duncan told of witnessing murders, torture and other atrocities by American forces in Vietnam in violation of all international laws; of refusing orders at An Khe to kill four enemy prisoners whose hands were tied behind them; and of rapes by South Vietnamese troops that were never reported, let alone punished.

Continue reading the main story

“The whole thing was a lie,” Mr. Duncan wrote. “We weren’t preserving freedom in South Vietnam. There was no freedom to preserve. To voice opposition to the government meant jail or death. Neutralism was forbidden and punished. Newspapers that didn’t say the right thing were closed down. People are not even free to leave, and Vietnam is one of those rare countries that doesn’t fill its American visa quota.”

By the late 1960s, as documented in David Cortright's "Soldiers in Revolt", more than 100 "underground" newspapers were being published by men and women in the American military who were opposing the U.S. wars against the peoples of Vietnam (and more broadly, "Indochina") and other issues. One of those newspapers, "Up Against the Bulkhead," was published out of San Francisco and distributed widely throughout the fleet to sailors, marines and some soldiers based on the West Coast.In 1967, Mr. Duncan joined the Rev. William Sloane Coffin Jr., Dr. Spock, David Dellinger and other leaders of the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, to plan and carry out huge protest rallies in New York, Washington, San Francisco and dozens of other cities, at which draft cards and American flags were burned and protesters clashed with the police.

By the late 1960s, as documented in David Cortright's "Soldiers in Revolt", more than 100 "underground" newspapers were being published by men and women in the American military who were opposing the U.S. wars against the peoples of Vietnam (and more broadly, "Indochina") and other issues. One of those newspapers, "Up Against the Bulkhead," was published out of San Francisco and distributed widely throughout the fleet to sailors, marines and some soldiers based on the West Coast.In 1967, Mr. Duncan joined the Rev. William Sloane Coffin Jr., Dr. Spock, David Dellinger and other leaders of the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, to plan and carry out huge protest rallies in New York, Washington, San Francisco and dozens of other cities, at which draft cards and American flags were burned and protesters clashed with the police.

Mr. Duncan also testified that year at an unofficial “war crimes tribunal” organized by the philosopher Bertrand Russell in Denmark, and at a South Carolina court-martial, where he spoke in defense of Capt. Howard R. Levy, a Green Beret who had also turned against the war. Captain Levy was convicted of disobeying orders and attempting to incite disloyalty, and eventually served 26 months in prison.

In 1968 Mr. Duncan, then the military editor of Ramparts, helped Mr. Dellinger, Mr. Gregory, Rennie Davis and other antiwar leaders plan protests at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The rallies and marches drew tens of thousands of protesters and led to hundreds of arrests and injuries, and to a circuslike trial of eight protest leaders on inciting-to-riot charges.

In his Ramparts articles and a memoir, “The New Legions” (1967), Mr. Duncan detailed a military career that began in December 1954, when he was drafted by the Army in Rochester, a 24-year-old American who had been born in Canada and raised by a stepfather of Hungarian origin.

“I was a militant anti-Communist,” Mr. Duncan wrote in Ramparts. “Like most Americans, I couldn’t conceive of anybody choosing communism over democracy. The depths of my aversion to this ideology was, I suppose, due in part to my being Roman Catholic, and in part to the stories in the news media about communism. My stepfather was born in Budapest, Hungary. Although he had come to the United States as a young man, most of his family stayed in Europe.”

Mr. Duncan was serving with an artillery unit in Germany in 1956 when the Soviet Union crushed the Hungarian revolt. He recalled being frustrated and angry when the United States did not intervene. He joined the Special Forces in 1961. “I was so impressed with their dedication and élan,” he said. “Their anti-Communism bordered on fanaticism.”

Special Forces training, he said, included “methods of torture to extract information,” including “the delicate operation of lowering a man’s testicles into a jeweler’s vise.” He said he later witnessed the use of such techniques in Vietnam.

He volunteered to fight in South Vietnam in 1964 and served in missions all over the country with the Fifth Special Forces Group. He killed the enemy, saw comrades killed, watched civilians shot and bayoneted and their villages burned. He was awarded South Vietnam’s Silver Star, the United States Army Air Medal, two Bronze Stars and the Combat Infantry Badge, and was recommended for a Silver Star and the Legion of Merit.

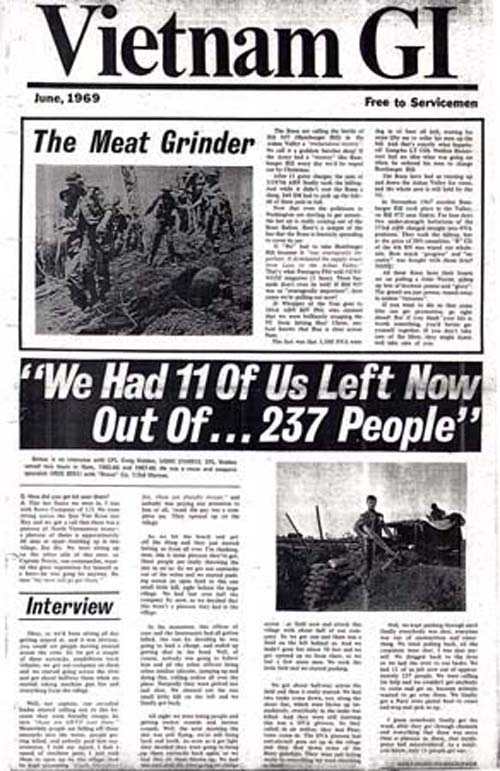

Published and distributed world wide from Chicago during the late 1960s and into the early 1970s, "Vietnam G.I." was one of the largest circulation "underground" newspapers of the G.I. Movement because of its unique labor intensive methods of getting the paper to thousands of readers in Vietnam. Above, the interview about "Force Recon" appears on the front page of Vietnam G.I.'s June 1969 edition. The interview exposed the fact that the military brass organized certain combat veteran marines and soldiers into "recon" units that were left in the "boonies" to fight until most of their members were dead (in the case of that unit, 11 out of more than 200). The military brass knew during the Vietnam War that a certain number of its soldiers would go "kill crazy" (the phrase used then) and could not be returned to civilian life. Cover above part of the Substance library.On reconnaissance in Laos, where United States bombers were pounding an enemy supply route, he began to doubt American reports on the war.

Published and distributed world wide from Chicago during the late 1960s and into the early 1970s, "Vietnam G.I." was one of the largest circulation "underground" newspapers of the G.I. Movement because of its unique labor intensive methods of getting the paper to thousands of readers in Vietnam. Above, the interview about "Force Recon" appears on the front page of Vietnam G.I.'s June 1969 edition. The interview exposed the fact that the military brass organized certain combat veteran marines and soldiers into "recon" units that were left in the "boonies" to fight until most of their members were dead (in the case of that unit, 11 out of more than 200). The military brass knew during the Vietnam War that a certain number of its soldiers would go "kill crazy" (the phrase used then) and could not be returned to civilian life. Cover above part of the Substance library.On reconnaissance in Laos, where United States bombers were pounding an enemy supply route, he began to doubt American reports on the war.

“This mission confirmed that the Ho Chi Minh Trail, so called, and the traffic on it, was grossly exaggerated,” he said, “and that the Vietcong were getting the bulk of their weapons from ARVN and by sea. It also was one more piece of evidence that the Vietcong were primarily South Vietnamese, not imported troops from the North.” (The ARVN was South Vietnam’s Army.)

Mr. Duncan said it had been common knowledge that draft-dodging and desertion rates among South Vietnamese troops were “staggering,” and that Vietcong guerrillas attacked American machine-gun positions “across open terrain with terrible losses.” American propaganda, he said, could not obscure such lopsided motivations.

“Even during the short period I had been in Vietnam,” he wrote, “the Vietcong had obviously gained in strength. The government controlled less and less of the country every day. The more troops and money we poured in, the more people hated us.”

He concluded that America was destined to lose the war. “I don’t think Vietnam will be better off under Ho’s brand of communism,” he said. “But it’s not for me or my government to decide. That decision is for the Vietnamese. I also know that we have allowed the creation of a military monster that will lie to our elected officials, and that both of them will lie to the American people.”

Donald Walter Duncan was born in Toronto on March 18, 1930, to Walter Cameron Duncan and the former Norma Brooker. Little is known of his early life. His father died when he was young, and his mother married Henry de Czanyi von Gerber, a naturalized American who became a noted cellist and orchestra conductor. His stepfather’s daughter, Frances (Donald’s stepsister), became the actress Mitzi Gaynor.

As a young man, Mr. Duncan was an office clerk, lumberjack, foundry worker and tree-topper. He married, had a child and divorced before being drafted. In West Germany in 1955, he married Apollonia Röesch. Their daughters are Ms. Casey and Ms. Wilson. After a second divorce, he married and divorced several more times. Besides Ms. Casey and Ms. Wilson, his survivors included at least two grandchildren, and Miss Gaynor.

After Mr. Duncan’s antiwar activities, he lived in Berkeley, Oakland and elsewhere in California. His daughters then lost track of him for years. He settled in Indiana around 1980, and in 1990 he became a founder of River Valley Resources, which provides services for the poor.

“Dad did not talk a whole lot about the war,” Ms. Wilson recalled. “But he was involved in a lot of antiwar things. We were young, but he wanted us to understand. He instilled in Val and me a sense of what’s right.”