Reader profile explains Chuy Garcia's decision to run for mayor... "Garcia offers voters a compelling personal history..."

A lengthy article in the January 22, 2015 edition of the Reader gives many Chicagoans the first in depth look at how Jesus "Chuy" Garcia decided to run for mayor of Chicago and a great deal about the man's background.

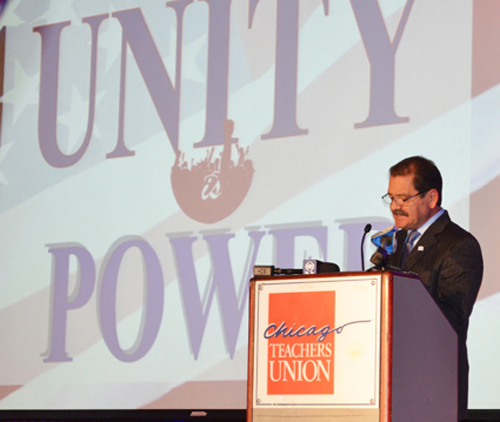

Chicago first learned that Jesus "Chuy" Garcia was in the running for mayor during the week before Halloween, when the Chicago Teachers Union teased the story by announcing that CTU President Karen Lewis would "appear" at the union's annual LEAD (Legislators Educators Appreciation Dinner) dinner. By the time of the dinner, CTU leaders were announcing that the union was going to support Garcia for mayor, since Lewis's serious illness had taken her out of the mayoral race. Substance photo by Sharon Schmidt.READER STORY PUBLISHED INTHE PRINT EDITION DATED JANUARY 22, 2015. [http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/jesus-chuy-garcia-rahm-emanuel-chicago-mayor-race-karen-lewis/Content?oid=16255514]

Chicago first learned that Jesus "Chuy" Garcia was in the running for mayor during the week before Halloween, when the Chicago Teachers Union teased the story by announcing that CTU President Karen Lewis would "appear" at the union's annual LEAD (Legislators Educators Appreciation Dinner) dinner. By the time of the dinner, CTU leaders were announcing that the union was going to support Garcia for mayor, since Lewis's serious illness had taken her out of the mayoral race. Substance photo by Sharon Schmidt.READER STORY PUBLISHED INTHE PRINT EDITION DATED JANUARY 22, 2015. [http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/jesus-chuy-garcia-rahm-emanuel-chicago-mayor-race-karen-lewis/Content?oid=16255514]

Jesus 'Chuy' Garcia's journey from a village in Mexico to the race against Mayor Emanuel Rahm Emanuel is a heavy favorite, but Garcia offers voters a compelling personal history.

By Steve Bogira @stevebogira

At Labor Day, Jesus "Chuy" Garcia spent four hours at Karen Lewis's house, discussing her plan to run against Mayor Rahm Emanuel. Garcia, 58, is a Cook County Board commissioner and a former alderman and state senator; Lewis, 61, is the fiery president of the Chicago Teachers Union. He's Mexican-American; she's African-American and Jewish. "We were strategizing her victory path," Garcia told me recently. "We talked plenty about conditions in the Latino community."

Lewis hadn't formally announced that she was running, but she'd begun raising money for the race and was considered a potent challenger to Emanuel. All that changed in early October; she experienced light-headedness and strokelike symptoms, and was diagnosed with a cancerous brain tumor. On October 8, she had emergency surgery, and a spokesman announced she wouldn't be running for mayor after all.

Soon after Lewis got home from the hospital, she invited Garcia over again. "I went as a well-wisher," he said. But he quickly learned Lewis had an agenda: she wanted him to run against Emanuel.

Garcia told me he was stunned. "What else did they do to you when you had your surgery?" he asked Lewis. She laughed and gave him a high five. But she persisted: "She said, 'Seriously, you need to think about this. The communities of Chicago need someone to be their standard-bearer.'"

"Why me?" he asked her.

Lewis told him his years as a community activist and his stellar political career made him an attractive candidate. She conceded that many black Chicagoans weren't aware of him, but she said they'd support him when they learned his history. She stressed his long-standing ties with labor and with gay and lesbian leaders, Jews and Muslims, and the city's leading liberals.

Garcia was flattered but uncertain. Lewis asked him to think it over and discuss it with his wife.

He and his wife, Evelyn, talked about it for a week. Evelyn has multiple sclerosis. Because her health had declined, she'd just taken early retirement from her job as a teacher's assistant in the Chicago Public Schools. Garcia had pledged to spend more time with her "to make sure she's taking care of herself, to go for walks with her as part of her therapy." Their three children are grown, but their three grandchildren visit often. The campaign would devour their family time and diminish their privacy, he told Evelyn.

But Evelyn thought he should run. "That's when I knew I was in trouble," he told me.

Jesus and Evelyn are residents of Little Village, a low-income Latino community on the southwest side. "I have my complaints about daily life in the neighborhood," Garcia said earlier this month. We were in the dining room of the modest three-bedroom home on 25th Place he and Evelyn bought 24 years ago. "Having to pick up people's dog poop and beer bottles in front of my house. Noise on 26th Street in the summer�loud music, screeching tires, people yelling, kids acting up.

"But it's still my community of choice, because there are good neighbors here," he went on. "They offer to help if you're shoveling snow, or if you're having trouble with your car. They'll call you if you leave your garage door open�'Hey, it's been open for the last hour, is that how you want it?' They'll bring food over�'We just made some carnitas,' 'Check out this salsa.' They'll come over with a six-pack on a hot summer day."

Little Village is still struggling to recover from the 2008-'09 recession. There's a boarded building�a foreclosed property�across the street from Jesus and Evelyn's home. Many residents are jobless. Shootings and killings have declined since Garcia helped create antiviolence programs in the neighborhood a decade ago. But he and Evelyn are still occasionally awakened by gunfire, followed by sirens. "Then your heart sinks, because of the likelihood you'll know whose child it is."

Garcia said he and Evelyn decided he should run "because we felt I could offer an alternative to what hasn't worked in Chicago in some time, certainly the past four years. We thought I had a responsibility to move a cause forward�the cause of everyday people in Chicago who are struggling to make ends meet, parents worrying about their children's safety, their education. And that there was the potential for a candidacy like mine to catch fire, and put the city on a different course."

He announced his candidacy in late October. In less than a month, volunteers gathered 63,000 signatures to get him on the ballot, far more than the 12,500 required, and the most of any candidate. He's been endorsed by prominent liberals�Cook County clerk David Orr, former state senator Miguel del Valle, venerable civil rights activist Timuel Black.

If his candidacy has caught fire, however, it's not evident from the campaign contributions he's received. Aside from a couple of big checks from labor groups, the money has dribbled in. He's collected $902,000, compared with $11.2 million for Emanuel. But then, most of the voters he's targeting haven't got much to spare�certainly not compared with the investment bankers and real estate developers who keep fattening Emanuel's reelection fund. (Among the other three contenders, businessman Willie Wilson has raised the most�$1.4 million�but all except $5,000 of that was from himself. Alderman Bob Fioretti has raised $455,000, and onetime mayoral aide Bill "Dock" Walls has raised $30,000.)

Like many challengers of incumbents, Garcia has put forth a platform that's long on proposals and short on ideas for funding them. He's called for more cops, counselors, and jobs for youth, smaller classes in the schools, more arts and language instruction, better parks and libraries. Missing have been remedies for the city's stubborn fiscal problems. He attributed this to his campaign's late start, and said proposals about finances will come; he has "some very bright people looking at a variety of things." The Reader will examine his recommendations when they're made, and take a closer look at his platform another time.

Can he win? Right now, Emanuel is a heavy favorite. A poll in early January by Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research�a firm working for the mayor�had Emanuel with 50 percent, Garcia with 22 percent, Fioretti with 10 percent, Wilson with 7 percent, and Walls with 2 percent. Nine percent were undecided.

If no candidate gets more than 50 percent on February 24, the top two finishers face each other in a runoff April 7. The January poll, plus the vast sums Emanuel has for advertising, make his odds of winning without a runoff good.

But five debates, the first one January 27, could change that. "If Chuy comes off in the debates as a guy who could run the city, he'll have a real chance," said UIC political science professor Dick Simpson, a former independent alderman.

Simpson said he supports Garcia because he believes he's "deeply committed to the neighborhoods and to empowering people." But he acknowledged a shortcoming Garcia has as a candidate: "He doesn't have the habit of easily crystallizing things. He's thoughtful, and that tends to slow down his response." In the debates, "he could come off as brilliant, or as someone who hasn't yet formulated his positions."

Latinos make up about a third of Chicago's population, but they're only 19 percent of its voting-age citizens. Garcia needs to do well among African-American voters, who make up 38 percent of the city's adult citizens; Emanuel has strong support from the 43 percent of adult citizens who are white.

Emanuel angered many African-Americans in 2013 by closing 50 underused schools, almost all of them in black neighborhoods. Garcia could tap into that discontent if black voters will support a Latino for mayor�but that's a big if. Lewis's endorsement helps, as does the fact that Garcia serves as floor leader for Chicago's most prominent African-American elected official, Cook County Board president Toni Preckwinkle. Garcia also was close to Harold Washington, Chicago's first black mayor.

Whether those connections translate into African-American backing for Garcia at the polls is the key question. Many blacks still see Latinos as rivals for jobs. "Early on, I heard people in the community saying, 'I can't vote for anyone Hispanic�I'm just not gonna do it,'" one veteran Chicago political consultant, an African-American, told me. She's consulting for a mayoral candidate other than Garcia, and so asked not to be named. But she said more aggressive efforts recently by the Garcia campaign to reach out to black voters may be helping him: "Lately, I haven't heard people being adamant about not voting for a Hispanic the way they were in the beginning."

What Garcia clearly offers voters is a compelling personal history. His stories about his past tend to highlight his humble, communal background, his empathy for the less fortunate, and his diplomatic skills and experience�qualities he believes a mayor ought to have and that distinguish him from the one in power.

The boarded building across the street from Garcia's home - JEFFREY MARINI

The boarded building across the street from Garcia's home

JEFFREY MARINI

Garcia's road to a big-city political career began in a small village in Mexico. He was born in Los Pinos, a village on the edge of a river near the Sierra Madre, in Durango. It had 200 inhabitants at most when he was a child; everyone was acquainted, and many were related. They gathered often for holiday celebrations and fiestas. Garcia's home was in the center of town; the church and school were across the street, so "everything that happened was right in front of my house."

He was the youngest of four children raised by their mother. Their father had picked fruits and vegetables in Texas and California before finding work in a cold-storage plant in Chicago in the late 1940s. He was undocumented until the early 1960s; he visited the family when he had time off.

Garcia remembers his childhood fondly. "Things got a bit scarce in the winter, but I never went hungry. There were always at least tortillas or tostadas, and you could put a little manteca on them�grease with salt." His mother milked a cow. His father's checks came regularly. The house was filled with music�church songs and country songs on a radio, or his mother, Celia, singing.

Celia organized the church choir and holiday celebrations and led prayers at wakes. She'd attended school only through third grade�the education of girls was a low priority in Mexico�but she'd taught herself reading and writing well enough that she served as a literacy teacher in Los Pinos. "Raising four kids by herself and being able to do that on the side, with a third-grade education, shows a high level of social consciousness," Garcia said. "I've run into people at wakes here who have told me she made a great difference in their lives, that she opened their eyes to the world by teaching them how to read and write.

"So I think it's her fault," he added with a chuckle, "that I developed a passion for people, and for thinking about how things can be, versus how they are."

In 1964, Garcia's father was able to get permanent residency status in the U.S. for himself and his family. The following February, when Garcia was ten, he and his siblings and their mother made the trip north in his uncle's station wagon, arriving in Pilsen on a snowy day.

After the intimacy of Los Pinos, Pilsen was a shock at first, especially because everyone was speaking an unfamiliar language. A lot of young Latino families lived in the blue-collar neighborhood, along with older eastern Europeans, but many of the Latino kids were U.S. natives and bilingual. "You see people pointing at you, and you know they're saying, 'He doesn't speak English.'"

He was constantly tested by kids in the neighborhood and at school. "They see if you can duck snowballs�and they pack 'em hard," he recalled. "They see if you fall when they push you in the snow. They talk at you in slang to show you up as a hick."

How did he respond? "If the snowball hurts, don't show it. Learn as fast as possible how to swear. When they push you, try your darnedest not to fall. Yeah, you push back sometimes, unless it's somebody who really would kick your butt."

His family lived on the 1600 block of Allport for two years, then moved to an apartment on 17th Street near Carpenter. By this time his English was much better, and he was growing to like the neighborhood. Seventeenth Street was "a great microcosm of the city and the country," with families of many ethnicities, he told me in December, when we toured his old haunts. He spent time with the black kids who lived on 16th Street, listening to soul music with them. He also heard the sermons of Martin Luther King on the radio. Living in Pilsen "was the most powerful civics lesson one could get," he said. "That was where I became opposed to stereotypes and racism, and open to people who are different."

Pilsen was rife with gangs, and as a young teen he also learned lessons in urban diplomacy. "You go to a party and guys ask you 'What you be about?' Meaning, 'What gang are you with?' That was always challenging. Because if you say, 'I'm not affiliated,' they'll say, 'You're lying. You're a punk.'" His response depended on the situation. "If you're at a friend's house and somebody says that, you look at your friend, and he says, 'Hey man, what's up with you? That's my friend, don't mess with him.' Or you throw it back in a different way to try to defuse the situation. Or sometimes you just call somebody's bluff. You know, 'You wanna find out?' It all takes calculation. Those situations are mined with potential violence, and navigating them becomes an art."

By 1969, Garcia's family had saved enough to buy their first home, and late that year they left Pilsen for "the suburb of Little Village," as Garcia likes to put it.

They were the first Mexican family on Pulaski near 28th. Little Village was changing rapidly then, with Latinos moving in and Poles, Czechs, and Germans leaving. The census tract Garcia's family moved into was 14 percent Hispanic in 1970, and 74 percent Hispanic ten years later. The poverty rate more than doubled in that decade, from 7 percent to 15 percent. But according to Garcia, the stream of hopeful immigrants from Mexico protected the neighborhood from more precipitous decline.

Garcia with his wife, Evelyn Chinea (and dog, Mia), in their Little Village home - JEFFREY MARINI

Garcia with his wife, Evelyn Chinea (and dog, Mia), in their Little Village home

JEFFREY MARINI

A history of racial tension plagued the neighborhood where Garcia attended high school, on 63rd near Western. The tension was exacerbated by neo-Nazi activists, whose headquarters were in the nearby Marquette Park area. "Their pamphlets would incite white students," Garcia recalled. "Kids would say things like, 'Hitler was right, white people unite.'"

Few Latinos or African-Americans attended his high school, Saint Rita, and he heard racial epithets inside and outside the school. "We got called spic, wetback, taco bender. That was the funniest one to me. I guess it had to do with the hard shells they sell for tacos. But taco bender? Do you think people sit around and bend it and shape it and package it?"

The bigotry aimed at minority students unified them, Garcia said. "There were 15 or 20 of us who hung out together and looked out for each other"�Mexican-Americans, African-Americans, Puerto Ricans, and several white kids "who we had become friends with and who understood what was going on." They'd meet up after school in a restaurant on Western, listen to music on the jukebox, and often talk about the bigotry they were experiencing. "We were able to frame it correctly�that it was fear, confusion. And that the kids who were prejudiced didn't become that way on their own�they were shaped by things they heard from their parents, their relatives, their neighbors." The group's discussions "were very healthy�they kept us from lashing back."

The summer before college, he worked at the Brach's candy factory on the west side. "You know the Starlight candies? We put the stripes on those suckers," he told me proudly. He worked the overnight shift, 11 PM to 7 AM, in the hard goods department, "where it was the hottest, and where the toughest guys were. I don't know why I wound up there�maybe because I was in pretty good shape, and had a goatee, and looked like I could handle it."

His coworkers were all older, and it was a racially diverse group. "I was the kid, and everybody would come slap me on the back�'Yeah, we're gonna make a man out of you.'

"You had a net on your head, a white shirt, an apron, and you're always sweating, but you learned to enjoy it, to take pride in holding up your end. You're pouring a vat of molten candy, and it has to cool on a steel bed. You put in the mint and menthol, roll it out, decorate it with the stripes. Then you throw it on another machine that stretches it and cuts it, and that's how you get the Starlights. They're still my favorite candies because I know what went into making them."

The job deepened his appreciation for factory workers. "It made me understand hard work and pride. Everybody wanted to have the best-looking candy."

He made good money�enough that by the end of the summer he was able to buy a '68 Chevy Malibu and dress it up with mag wheels. It looked so sharp that it got stolen. He found it in an industrial area near the Brach's factory, sans the mags�it was parked on four milk crates. "I didn't put shiny rims on it after that."

The summer after his freshman year at the University of Illinois's Chicago campus (later UIC), Garcia met a veteran Latino activist named Lola Navarro. She was a disciple of Saul Alinsky, the celebrated Chicago community organizer who advocated "direct actions" such as sit-ins and picketing. Navarro's targets had included the Board of Education, for its overcrowded public schools in Pilsen and Little Village, and the CTA, for its reluctance to hire Latinos.

Following Navarro's example, Garcia and his friends decided to picket the Atlantic movie theater, on 26th Street near Pulaski. The building was decrepit, and rats roamed its halls. "People saw us picketing, and they were like, 'You guys are right, this is bullshit, it's insulting,' and they wouldn't go in the theater. The owner shut it down and cleaned it up. No protracted negotiations or anything. It was like, 'Wow, so this is how you organize.'"

Later that summer, Garcia and his cohorts confronted a city official who ran a youth jobs program in Little Village. The only kids who were getting jobs were politically connected. "A group of us went over there one day and requested to meet with him." They were told he wasn't in. "We said, 'Well, we're going to wait for him.' And we waited and waited and he didn't come back. So we went into his office and took it over, and we demanded a meeting with him. The police were summoned, but they were hesitant to arrest us." Then the official showed up. "At first he said he couldn't do anything, then he said he might be able to do something, and toward the end of the meeting he said he would do everything possible. The short of it was, a group of kids got jobs that summer working with children."

At college his sophomore year, Garcia and other students took over the chancellor's office at University Hall. That led to negotiations that resulted in the creation of the Latin American Cultural Center. When the center had its grand opening in October 1977, Garcia was emcee. The center is flourishing today.

In 1977, Garcia also became friends with Rudy Lozano.

Lozano was four years older and had preceded Garcia at the UI's Chicago campus. He was organizing factory workers in Pilsen and Little Village, and advocating for unconditional amnesty for undocumented immigrants. The support for immigrants impressed Garcia, because Lozano had been born in the U.S. "I thought that people who were born here saw us as a step down, but he accepted everyone as equals."

Garcia accompanied Lozano on some of his visits to shops to talk with workers about conditions, and to urge them to unionize. Employers occasionally responded by calling the police or otherwise trying to chase them off. "You had to push back," Garcia said. "You had to show some guts, because you needed to let workers know they could do this."

Lozano believed that Latinos also needed to get involved in politics. In 1981, he and Garcia gave an award at a union hall to south-side congressman Harold Washington for his efforts in Congress on behalf of immigrants and bilingual education�causes that went beyond Washington's constituency.

"That's when Evelyn and I saved Harold's life," Garcia told me with a broad smile. "He started to choke on some mole that we served him�it went down the wrong pipe." Garcia pounded him on the back, Evelyn gave him some water, "and he cleared his throat, he was better. But he was still having a rough time, so Evelyn and I whisked him to the kitchen so he could get his composure. Then he goes, 'What'd you say your name was?' And I told him Jesus. He goes, 'Jesus? How do you spell that?'" Garcia spelled it for him, and Washington roared. "And he goes, 'Jesus�you saved my life.' He knew who I was from that point on."

The ward that included Little Village, the 22nd, was predominantly Latino in the early 1980s, but it was represented by a white Democratic machine alderman. In 1983, Lozano ran against him, with Garcia managing his campaign.

Meanwhile, Washington was running against incumbent Jane Byrne and state's attorney Richard M. Daley for the Democratic nomination for mayor. (Chicago's mayoral election has since become nonpartisan.) Because Lozano and Garcia believed in a multiracial coalition, they made sure their volunteers also passed literature for Washington, even though they knew it might cost Lozano votes; Washington wasn't yet popular in the 22nd Ward. In a five-person aldermanic race that February, Lozano finished second, 17 votes shy of forcing the incumbent into a runoff. Washington sneaked by Byrne and Daley in the mayoral primary, and in April he won the general election and became the city's first African-American mayor.

Less than two months later, on a June morning in 1983, Lozano was fatally shot in the kitchen of his home on 25th Street near Pulaski. He was 31.

A teen gang member was arrested and later convicted of the murder. The motive was never clear. Prosecutors maintained at the trial that Lozano had used gang members in his campaign for alderman, unintentionally weakening the gang to which Lozano's killer belonged.

Garcia told me he and Lozano did their best to keep gang members out of Lozano's campaign, "but when people volunteer, you don't know who they are, and you can't weed everybody out." He said he still believes that forces "on the labor front or the political front" who felt threatened by Lozano were behind the slaying.

Because the motive for the murder was unclear, Garcia and his friends worried that whoever was responsible might not be finished.

Lozano's death "was one of the most difficult things to process," Garcia told me. "Rudy and I were inseparable." He paused, and looked away. When his eyes returned, they were wet, and his voice cracked as he continued. "I was dealing with the loss, the grief, the suspense, all at the same time."

He'd been comfortable offstage, but after Lozano was killed he realized he needed to become the candidate who would help their movement succeed.

"I did it in part to keep his memory alive," Garcia said. "We thought getting elected was one of the most important statements we could make in terms of justice, politically and socially, for Rudy. It motivated me to run then, and it still does."

Harold Washington and Garcia at a memorial for Rudy Lozano a year after his death - CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

Harold Washington and Garcia at a memorial for Rudy Lozano a year after his death

CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

In 1984, Garcia ran for Democratic ward committeeman in the 22nd. The efforts he and Lozano had made to build a multiracial coalition bore fruit: the only two black precincts in the ward voted overwhelmingly for Garcia, lifting him to victory in a tight race against the machine incumbent.

Two years later, in a special election after a court-ordered ward remap, Garcia was elected alderman. The opposition of white aldermen had prevented Mayor Washington from passing legislation and securing appointments; Garcia helped break that logjam, and he soon became the ranking Latino in the mayor's council coalition.

Garcia is also proud that services in his ward were fairly distributed while he was alderman. One of his longtime supporters, Ronelle Mustin, an African-American truck driver who's lived in the ward since 1977, said Garcia made sure the ward's few black residents "got our fair share of everything�streets repaired, sidewalks done, garbage picked up." Garcia was reelected in 1987. In 1991, the Independent Voters of Illinois named him one of the city's best aldermen, and he was reelected again.

But after Washington died in office in 1987, and especially after Daley was elected mayor in 1989, the council reverted to its customary rubber-stamp role, and Garcia decided it was time to move on. In 1992 he became the first Mexican-American to be elected to the Illinois state senate. The rewards of representing a larger district more than offset the pay cut, he told me; aldermen then made $55,000, state senators $38,500.

The Tribune endorsed him for reelection in 1996, calling him "one of the more independent and open-minded Chicago legislators." He won, and in his second term the Wall Street Journal lauded his efforts to work with different races and ethnicities, noting that he was chairing the predominantly African-American senate minority caucus.

In 1997, Garcia opposed the UIC's southward expansion into Pilsen and the Near West Side. The university offered a plan that in the short term would bring more jobs and contracts to the affected neighborhoods, but Garcia feared it would hasten gentrification. He called for UIC to build more affordable housing in the area. In testimony before the board of trustees, he said the university had to choose between being an "arrogant, insensitive, bulldozing powerhouse" and an institution that "learned to involve its neighbors . . . as true partners." (This closely foreshadowed his view of the choice in the current mayor's race.)

His demands of UIC were unheeded. The Tribune endorsed him again in 1998, but with much less enthusiasm; the paper urged him to be "a conciliator, not an obstructionist." An army of precinct workers aligned with Mayor Daley helped a political neophyte turn Garcia out of office. The Tribune attributed Garcia's loss partly to his "overheated charges of gentrification" regarding UIC's expansion.

Garcia dropped out of politics after the 1998 defeat. He wanted to return to his roots of addressing problems at the community level, he told me.

He founded Enlace Chicago, a nonprofit community development organization in Little Village, and served as its executive director while taking evening classes in urban planning at UIC.

Rahm Emanuel also dropped out of politics at about this time: in 1998, he left his position as an adviser to President Clinton, and the following year, despite having no formal education in finance, he found work as an investment banker. In his two-and-a-half years in that position, he made $16 million. Then he got back into politics, running for Congress in 2002.

Garcia said that moving from the state senate to Enlace meant another pay cut, "but it was very rewarding."

In ten years, he built Enlace�which means "connections"�into an organization with a $2.9 million budget and a full-time and part-time staff of more than a hundred. It's been instrumental in antiviolence efforts in Little Village and in upgrading housing there. On Mother's Day in 2001, a protest engineered by Garcia�a 19-day hunger strike by parents�won a commitment by the Chicago Public Schools to finally build a long-promised high school, Little Village-Lawndale. It opened in 2005.

In 2009, Garcia decided it was time for other challenges. At a large staff meeting, he announced he was leaving Enlace. "There wasn't a dry eye in the room," said Mike Rodriguez, Enlace's current executive director.

The following year, Garcia won a seat on the county board. He said he was enticed back into politics because Preckwinkle, another veteran liberal, was running for board president. "I thought I could lend a hand with a reformer at the helm." Preckwinkle made him her floor leader even though he was new to the board. They both won second terms in November.

With his county board position, "I reached a balance in my life," Garcia said. "I was able to be a legislator, an advocate�and a good father, husband, and grandfather."

Then Karen Lewis called and upset the balance.

Garcia at the Chicago Teachers Union�s October 2014 Legislators and Educators Appreciation Dinner - CHANDLER WEST/SUN-TIMES MEDIA

Garcia at the Chicago Teachers Union�s October 2014 Legislators and Educators Appreciation Dinner

CHANDLER WEST/SUN-TIMES MEDIA

The campaign has been a grind so far, as Garcia knew it would be. He spends his days crisscrossing the city, shaking hands at el stops and intersections, making speeches, giving interviews, shaking more hands at dinners. When we spoke at his home on a morning in late December, he seemed weary; he was coming off the flu, which had been followed by a toothache, which had required an extraction. When we talked again in early January, he seemed reenergized.

We discussed the money Emanuel was hauling in, much of it from out-of-town donors. "It's a sad commentary on the state of democracy," Garcia said. "I would hope that people would say, 'Enough of that. We're intelligent, we have things we want to see happen in Chicago neighborhoods, and it's time to take Chicago back.' The biggest challenge we face is people thinking that this could be an invincible force, with millionaires and billionaires lined up against ordinary people. We want to show that it's doable.

"Rahm has spent most of his life being friendly with and working for the powerful, and raising money for Washington politicians," Garcia went on. "I've spent my life targeting powerful politicians, to make them respond to the needs of ordinary people. My emphasis has been in the trenches, grassroots, in schools and churches, on the street�and his has been in the halls of power."