Absurdities of computer-graded 'writing' exposed by BABEL

[While a great deal of blogging is kin to the selfie -- all opinion and no reporting with little fact. That is not true, however, about several blogs devoted to education, and one of the foremost among those comes from Diane Ravitch. Ravitch's sharp break with corporate "education reform" came after she had served for more than 20 years as one of the corporate reformers sharpest and most widely traveled defenders. Then she published The Death and Life of the Great American School System a defense of public education against reform (which she noted as many of us had was pushing union busting and privatization). The Death and Life was followed by her current book "Reign of Error..." which didn't get the time it deserved on the New York Times Best Seller List because not enough teachers invested in the book across the USA in time (it was virtually required reading for the leaders of the Chicago Teachers Union and CORE, however). Today, September 3, 2014, she posted a delightful essay on her blog about why computers can read writing and separate nonsense from decent human prose. As we face the drive for Common Core, it's worth reading. George N. Schmidt, Editor, Substance].

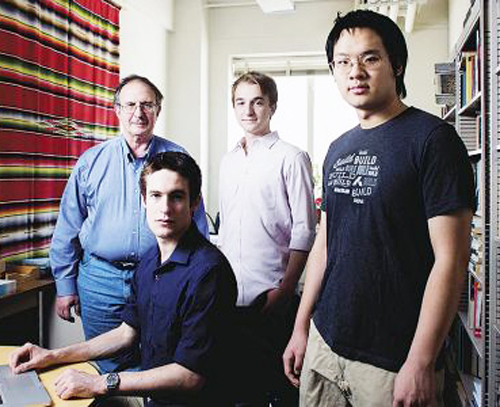

MIT's Les Perelman (left) with students. Perelman invented BABEL to "write" prose that scores high as computer graded essays, but is meaningless. BABEL generates bizarre prose, which tests highly� Computers can�t grade what you write right? Right!

MIT's Les Perelman (left) with students. Perelman invented BABEL to "write" prose that scores high as computer graded essays, but is meaningless. BABEL generates bizarre prose, which tests highly� Computers can�t grade what you write right? Right!

Diane Ravitch on September 3, 2014

In the brave new world of Common Core, all tests will be delivered online and graded by computers. This is supposed to be faster and cheaper than paying teachers or even low-skill hourly workers or read student essays.

But counting on machines to grade student work is a truly bad idea. We know that computers can't recognize wit, humor, or irony. We know that many potentially great writers with unconventional writing styles would be declared failures (EE Cummings immediately to mind).

But it is worse than that. Computers can't tell the difference between reasonable prose and bloated nonsense. Les Perelman, former director of undergraduate writing at MIT, created a machine, withe help of a team of students, called BABEL.

He was interviewed by Steve Kolowich of The Chronicle of Higher Education, who wrote:

"Les Perelman, a former director of undergraduate writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, sits in his wife�s office and reads aloud from his latest essay.

"Privateness has not been and undoubtedly never will be lauded, precarious, and decent," he reads. "Humankind will always subjugate privateness."

Not exactly E.B. White. Then again, Mr. Perelman wrote the essay in less than one second, using the Basic Automatic B.S. Essay Language Generator, or Babel, a new piece of weaponry in his continuing war on automated essay-grading software.

"The Babel generator, which Mr. Perelman built with a team of students from MIT and Harvard University, can generate essays from scratch using as many as three keywords.

"For this essay, Mr. Perelman has entered only one keyword: "privacy." With the click of a button, the program produced a string of bloated sentences that, though grammatically correct and structurally sound, have no coherent meaning. Not to humans, anyway. But Mr. Perelman is not trying to impress humans. He is trying to fool machines.

"Software vs. Software

"Critics of automated essay scoring are a small but lively band, and Mr. Perelman is perhaps the most theatrical. He has claimed to be able to guess, from across a room, the scores awarded to SAT essays, judging solely on the basis of length. (It�s a skill he happily demonstrated to a New York Times reporter in 2005.) In presentations, he likes to show how the Gettysburg Address would have scored poorly on the SAT writing test. (That test is graded by human readers, but Mr. Perelman says the rubric is so rigid, and time so short, that they may as well be robots.)

"In 2012 he published an essay that employed an obscenity (used as a technical term) 46 times, including in the title.

"Mr. Perelman�s fundamental problem with essay-grading automatons, he explains, is that they "are not measuring any of the real constructs that have to do with writing." They cannot read meaning, and they cannot check facts. More to the point, they cannot tell gibberish from lucid writing."

The rest of the article reviews projects in which professors claim to have perfected machines that are as reliable at judging student essays as human graders.

I'm with Perelman. If I write something, I have a reader or an audience in mind. I am writing for you, not for a machine. I want you to understand what I am thinking. The best writing, I believe, is created by people writing to and for other people, not by writers aiming to meet the technical specifications to satisfy a computer program.

APRIL ARTICLE BELOW HERE

April 28, 2014

Writing Instructor, Skeptical of Automated Grading, Pits Machine vs. Machine

By Steve Kolowich, Chronicle of Higher Eduction

Les Perelman, a former director of undergraduate writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, sits in his wife�s office and reads aloud from his latest essay.

"Privateness has not been and undoubtedly never will be lauded, precarious, and decent," he reads. "Humankind will always subjugate privateness."

Not exactly E.B. White. Then again, Mr. Perelman wrote the essay in less than one second, using the Basic Automatic B.S. Essay Language Generator, or Babel, a new piece of weaponry in his continuing war on automated essay-grading software.

The Babel generator, which Mr. Perelman built with a team of students from MIT and Harvard University, can generate essays from scratch using as many as three keywords.

For this essay, Mr. Perelman has entered only one keyword: "privacy." With the click of a button, the program produced a string of bloated sentences that, though grammatically correct and structurally sound, have no coherent meaning. Not to humans, anyway. But Mr. Perelman is not trying to impress humans. He is trying to fool machines.

Software vs. Software

Critics of automated essay scoring are a small but lively band, and Mr. Perelman is perhaps the most theatrical. He has claimed to be able to guess, from across a room, the scores awarded to SAT essays, judging solely on the basis of length. (It�s a skill he happily demonstrated to a New York Times reporter in 2005.) In presentations, he likes to show how the Gettysburg Address would have scored poorly on the SAT writing test. (That test is graded by human readers, but Mr. Perelman says the rubric is so rigid, and time so short, that they may as well be robots.)

In 2012 he published an essay that employed an obscenity (used as a technical term) 46 times, including in the title.

Mr. Perelman�s fundamental problem with essay-grading automatons, he explains, is that they "are not measuring any of the real constructs that have to do with writing." They cannot read meaning, and they cannot check facts. More to the point, they cannot tell gibberish from lucid writing.

He has spent the past decade finding new ways to make that point, and the Babel Generator is arguably his cleverest stunt to date. Until now, his fight against essay-grading software has followed the classic man-versus-machine trope, with Mr. Perelman criticizing the automatons by appealing to his audience�s sense of irony.

By that measure, the Babel Generator is a triumph, turning the concept of automation into a farce: machines fooling machines for the amusement of human skeptics.

Now, here in the office, Mr. Perelman copies the nonsensical text of the "privateness" essay and opens MY Access!, an online writing-instruction product that uses the same essay-scoring technology that the Graduate Management Admission Test employs as a second reader. He pastes the nonsense essay into the answer field and clicks "submit."

Immediately the score appears on the screen: 5.4 points out of 6, with "advanced" ratings for "focus and meaning" and "language use and style."

Mr. Perelman sits back in his chair, victorious. "How can these people claim that they are grading human communication?"

Challenging Evidence

In person, Mr. Perelman, 66, does not look like a crusader. He wears glasses and hearing aids, and his mustache is graying. He speaks in a deliberate, husky baritone, almost devoid of inflection, which makes him sound perpetually weary.

But this effect belies his appetite for the fight. Although he retired from MIT in 2012, he persists as a thorn in the side of testing companies and their advocates.

In recent years, the target of his criticism has been Mark D. Shermis, a former dean of the College of Education at the University of Akron. In 2012, Mr. Shermis and his colleagues analyzed 22,000 essays from high-school and junior-high students that had been scored by both humans and software programs from nine major testing companies. They concluded that the robots awarded scores that were reliably similar to those given by humans on the same essays.

Mr. Perelman took Mr. Shermis and his fellow researchers to task in ablistering critique, accusing them of bad data analysis and suggesting a retraction.

Mr. Shermis, a psychology professor, says he has not read the critique. "I�m not going to read anything Les Perelman ever writes," he told The Chronicle.

The Akron professor says he has run additional tests on the data since the first study and found nothing to contradict the original findings. He published a follow-up paper this year. Mr. Perelman says he is drafting a rebuttal.

The Prof in the Machine

Some of the most interesting work in automated essay grading has been happening on the other side of the MIT campus. That�s where computer scientists at edX, the nonprofit online-course provider co-founded by the university, have been developing an automated essay-scoring system of their own. It�s called the Enhanced AI Scoring Engine, or EASE.

Essentially, the edX software tries to make its machine graders more human. Rather than simply scoring essays according to a standard rubric, the EASE software can mimic the grading styles of particular professors.

A professor scores a series of essays according to her own criteria. Then the software scans the marked-up essays for patterns and assimilates them. The idea is to create a tireless, automated version of the professor that can give feedback on "a much broader amount of work, dramatically improving the amount and speed of formative assessment," says Piotr Mitros, chief scientist at edX.

Some of edX�s university partners have used EASE, which is open source, in their massive open online courses. Because of larger-than-usual enrollments, MOOCs often rely on peer grading to provide feedback on writing assignments. The peer graders are humans, true. But because they are not professional readers (and, in some cases, are not native English speakers), their scores are not necessarily reliable.

All grading systems have weaknesses, says Mr. Mitros. "Machines cannot provide in-depth qualitative feedback," he says. At the same time, "students are not qualified to assess each other on some dimensions," and "instructors get tired and make mistakes when assessing large numbers of students."

Ideally a course would use a combination of methods, says Mr. Mitros, with each serving as a fail-safe check on the others. If the EASE system and the peer graders yielded markedly different scores, an instructor might be called in to offer an expert opinion.

Mr. Perelman says he has no strong objections to using machine scoring as a supplement to peer grading in MOOCs, which he believes are "doing the Lord�s work." But Mr. Mitros and his edX colleagues see applications for EASE in traditional classrooms too. Some professors are already using it.

Bots at Work

Daniel A. Bonevac, a philosophy professor at the University of Texas at Austin, is one of them. Last fall he taught "Ideas of the Twentieth Century" as both a MOOC and a traditional course at Austin. He assigned three essays.

He calibrated the edX software by scoring a random sample of 100 essays submitted by students in the MOOC version of the course�enough, in theory, to teach the machines to mimic his grading style.

The professor then unleashed the machines on the essays written by the students in the traditional section of the course. He also graded the same essays himself, and had his teaching assistants do the same. After the semester ended, he compared the scores for each essay.

The machines did pretty well. In general, the scores they gave lined up with those given by Mr. Bonevac�s human teaching assistants.

Sometimes the software was overly generous. "There were some C papers that it did give A�s to, and I�m not sure why," says Mr. Bonevac. In some cases, he says, the machines seemed to assume that an essay was better than it really was simply because the bulk of the essays written on the same topic had earned high scores.

In other cases, the machines seemed unreasonably stingy. The College of Pharmacy also tested the edX software in one of its courses, and in that trial the machines sometimes assigned scores that were significantly lower than those given by the instructor. Meanwhile, in the MOOC versions of both courses, the machines were much harsher than instructors or teaching assistants when grading essays by students who were not native English speakers.

For his part, Mr. Bonevac remains optimistic that machines could play some role in his teaching. "For a large on-campus course," he says, "I think this is not far away from being an applicable tool."

In Mr. Perelman�s view, just because something is applicable does not mean it should be applied. The Babel Generator has fooled the edX software too, he says, suggesting that even artificially intelligent machines are not necessarily intelligent enough to recognize gibberish.

�Like We Are Doing Science�

At the same time, he has made an alliance with his former MIT colleagues at edX. He used to teach a course with Anant Agarwal, chief executive of edX, back in the 1990s, and says they have been talking about running some experiments to see if the Babel Generator can be used to inoculate EASE against some of the weaknesses the generator was designed to expose.

"I am not an absolutist, and I want to be clear about that," says Mr. Perelman. He maintains that his objections to Mr. Shermis and others are purely scientific. "With Anant and Piotr" at edX, he says, "it feels like we are doing science."

Mr. Shermis says that Mr. Perelman, for all his bluster, has contributed little to improved automated writing instruction. The technology is not perfect, he says, but it can be helpful.

Mr. Perelman, however, believes he is on the right side of justice: Employing machines to give feedback on writing to underprivileged students, he argues, enables the "further bifurcation of society" and can be especially damaging to English-language learners.

"I�m the kid saying, �The emperor has no clothes,�" says Mr. Perelman. "OK, maybe in 200 years the emperor will get clothes. When the emperor gets clothes, I�ll have closure. But right now, the emperor doesn�t."