The Brown decision in May 1954 did not say 'Close the achievement gap...' Segregation in Chicago and across the USA 'worst' as 60th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education approaches

May 17, 2014 will be the 60th anniversary of the historic U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, and protests against segregation in Chicago will be held at the site of one of the examples of the segregationists regime of Rahm Emanuel, Barbara Byrd Bennett, and David Vitale. Chicago is not quite the most segregated city in the USA, according to the latest update from the Civil Rights Project at UCLA -- just almost the most segregated. And those who rule Chicago in 2014, as they have since 1954, continue to try to act as if a certain kind of racial segregation is OK as long as they don't talk like Donald Sterling and get themselves photographed regularly surrounded by black children, as Rahm Emanuel does.

First, let's read the definitive words that brought tears to the eyes of generations, and led some to believe that the long march towards equality in the USA would be made a little easier: "We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal..." the Supreme Court wrote. (The entire decision is below).

With the approach of the 60th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, groups across Chicago are planning to mark the day by demanding to know why the Chicago Board of Education continues a ruthless segregationist policy. Only in 2014, the segregationists do not wear white robes and burn crosses, they come in all colors, wear business suits, and proclaim that the objective of public education in a democracy is to "end the achievement gap." It is as if Barbara Byrd Bennett, Rahm Emanuel, and David Vitale were allowed to turn history on its head and proclaim, with Hollywood backing, that the U.S. Supreme Court had never said that "separate is inherently unequal," but instead upheld the apartheid doctrine of separate but equal and reminded segregated school systems across much of the United States that the objective of schools was to "close the achievement gap."

The 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregation, not a so-called "achievement gap," was unconstitutional. And so Chicago will be marking the day and noting the work of the new segregationists, many of whom are African Americans.

The 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregation, not a so-called "achievement gap," was unconstitutional. And so Chicago will be marking the day and noting the work of the new segregationists, many of whom are African Americans.

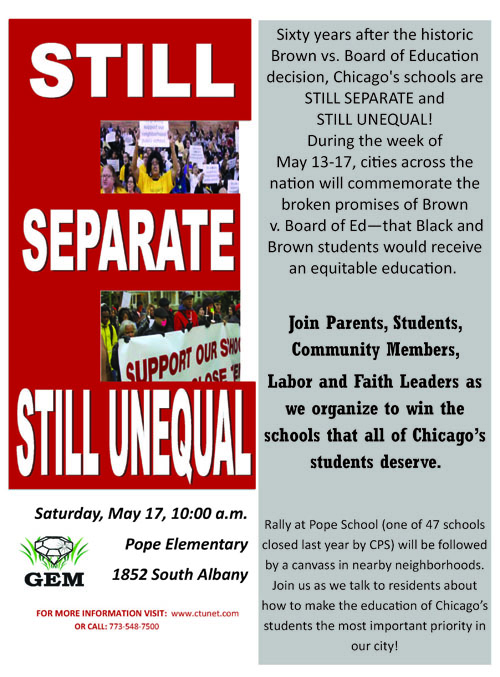

Sixty years after the historic Brown vs. Board of Education decision, Chicago's schools are still separate and still unequal. On Saturday, May 17, 2014, Chicago Teachers Union members and community supporters from across the city will mark the anniversary of Brown by protesting the apartheid in Chicago schools today.

In a joint call to action, GEM says "join parents, students, community members, labor and faith leaders as we organize and spread the word in several Chicago communities about the fight to win the schools that all our students deserve."

Saturday, May 17, 2014

Pope Elementary

1852 S. Albany Ave.

10-11 a.m. rally

12-2 p.m. community outreach

Endorsers and Supporters include:

Action Now, Albany Park Neighborhood Council, BAM, Bridgeport Alliance, Brighton Park Neighborhood Council, Chicago ACTS Local 4343, Chicago Students Union, Chicago Teachers Union, Hope Center, Jobs with Justice- Chicago, Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, Lawndale Alliance, McKinley Park Progressive Alliance, Northside Action for Justice, ONE Northside, Parents for Teachers, People for Community Recovery, Pilsen Alliance, SEIU - Health Care Illinois Indiana, Southsiders Together Organizing for Power, Southwest Side Parents Alliance, Teachers for Social Justice, VOYCE (list in formation)

MORE INFORMATION:

Jaribu Lee

Kenwood Oakland Community Organization

773-548-7500

COMPLETE TEXT OF BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION, ANNOUNCED BY THE U.S. SUPREME COURT ON MAY 17, 1954.

347 U.S. 483

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (No. 1.)

Argued: Argued December 9, 1952

Decided: Decided May 17, 1954

___

Syllabus

Opinion, Warren

Syllabus

Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment -- even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors of white and Negro schools may be equal. Pp. 486-496.(a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education. Pp. 489-490.(b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Pp. 492-493.(c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. P. 493.(d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal. Pp. 493-494.(e) The "separate but equal" doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, has no place in the field of public education. P. 495.(f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees. Pp. 495-496.

TOP

Opinion

WARREN, C.J., Opinion of the Court

[p*486] MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court.

These cases come to us from the States of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. They are premised on different facts and different local conditions, but a common legal question justifies their consideration together in this consolidated opinion. [n1] [p487]

In each of the cases, minors of the Negro race, through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of their community on a nonsegregated basis. In each instance, [p488] they had been denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. In each of the cases other than the Delaware case, a three-judge federal district court denied relief to the plaintiffs on the so-called "separate but equal" doctrine announced by this Court in Plessy v. Fergson, 163 U.S. 537. Under that doctrine, equality of treatment is accorded when the races are provided substantially equal facilities, even though these facilities be separate. In the Delaware case, the Supreme Court of Delaware adhered to that doctrine, but ordered that the plaintiffs be admitted to the white schools because of their superiority to the Negro schools.

The plaintiffs contend that segregated public schools are not "equal" and cannot be made "equal," and that hence they are deprived of the equal protection of the laws. Because of the obvious importance of the question presented, the Court took jurisdiction. [n2] Argument was heard in the 1952 Term, and reargument was heard this Term on certain questions propounded by the Court. [n3] [p489]

Reargument was largely devoted to the circumstances surrounding the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It covered exhaustively consideration of the Amendment in Congress, ratification by the states, then-existing practices in racial segregation, and the views of proponents and opponents of the Amendment. This discussion and our own investigation convince us that, although these sources cast some light, it is not enough to resolve the problem with which we are faced. At best, they are inconclusive. The most avid proponents of the post-War Amendments undoubtedly intended them to remove all legal distinctions among "all persons born or naturalized in the United States." Their opponents, just as certainly, were antagonistic to both the letter and the spirit of the Amendments and wished them to have the most limited effect. What others in Congress and the state legislatures had in mind cannot be determined with any degree of certainty.

An additional reason for the inconclusive nature of the Amendment's history with respect to segregated schools is the status of public education at that time. [n4] In the South, the movement toward free common schools, supported [p490] by general taxation, had not yet taken hold. Education of white children was largely in the hands of private groups. Education of Negroes was almost nonexistent, and practically all of the race were illiterate. In fact, any education of Negroes was forbidden by law in some states. Today, in contrast, many Negroes have achieved outstanding success in the arts and sciences, as well as in the business and professional world. It is true that public school education at the time of the Amendment had advanced further in the North, but the effect of the Amendment on Northern States was generally ignored in the congressional debates. Even in the North, the conditions of public education did not approximate those existing today. The curriculum was usually rudimentary; ungraded schools were common in rural areas; the school term was but three months a year in many states, and compulsory school attendance was virtually unknown. As a consequence, it is not surprising that there should be so little in the history of the Fourteenth Amendment relating to its intended effect on public education.

In the first cases in this Court construing the Fourteenth Amendment, decided shortly after its adoption, the Court interpreted it as proscribing all state-imposed discriminations against the Negro race. [n5] The doctrine of [p491] "separate but equal" did not make its appearance in this Court until 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, involving not education but transportation. [n6] American courts have since labored with the doctrine for over half a century. In this Court, there have been six cases involving the "separate but equal" doctrine in the field of public education. [n7] In Cumming v. County Board of Education, 175 U.S. 528, and Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78, the validity of the doctrine itself was not challenged. [n8] In more recent cases, all on the graduate school [p492] level, inequality was found in that specific benefits enjoyed by white students were denied to Negro students of the same educational qualifications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337; Sipuel v. Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 631; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637. In none of these cases was it necessary to reexamine the doctrine to grant relief to the Negro plaintiff. And in Sweatt v. Painter, supra, the Court expressly reserved decision on the question whether Plessy v. Ferguson should be held inapplicable to public education.

In the instant cases, that question is directly presented. Here, unlike Sweatt v. Painter, there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other "tangible" factors. [n9] Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education.

In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back to 1868, when the Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896, when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout [p493] the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.

Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does.

In Sweatt v. Painter, supra, in finding that a segregated law school for Negroes could not provide them equal educational opportunities, this Court relied in large part on "those qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness in a law school." In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, supra, the Court, in requiring that a Negro admitted to a white graduate school be treated like all other students, again resorted to intangible considerations: ". . . his ability to study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with other students, and, in general, to learn his profession." [p*494] Such considerations apply with added force to children in grade and high schools. To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this separation on their educational opportunities was well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a court which nevertheless felt compelled to rule against the Negro plaintiffs:Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system. [n10] Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this finding is amply supported by modern authority. [n11] Any language [p495] in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this finding is rejected.

We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This disposition makes unnecessary any discussion whether such segregation also violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. [n12]

Because these are class actions, because of the wide applicability of this decision, and because of the great variety of local conditions, the formulation of decrees in these cases presents problems of considerable complexity. On reargument, the consideration of appropriate relief was necessarily subordinated to the primary question -- the constitutionality of segregation in public education. We have now announced that such segregation is a denial of the equal protection of the laws. In order that we may have the full assistance of the parties in formulating decrees, the cases will be restored to the docket, and the parties are requested to present further argument on Questions 4 and 5 previously propounded by the Court for the reargument this Term [n13] The Attorney General [p496] of the United States is again invited to participate. The Attorneys General of the states requiring or permitting segregation in public education will also be permitted to appear as amici curiae upon request to do so by September 15, 1954, and submission of briefs by October 1, 1954. [n14]

It is so ordered.

* Together with No. 2, Briggs et al. v. Elliott et al., on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, argued December 9-10, 1952, reargued December 7-8, 1953; No. 4, Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al., on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, argued December 10, 1952, reargued December 7-8, 1953, and No. 10, Gebhart et al. v. Belton et al., on certiorari to the Supreme Court of Delaware, argued December 11, 1952, reargued December 9, 1953.

1. In the Kansas case, Brown v. Board of Education, the plaintiffs are Negro children of elementary school age residing in Topeka. They brought this action in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas to enjoin enforcement of a Kansas statute which permits, but does not require, cities of more than 15,000 population to maintain separate school facilities for Negro and white students. Kan.Gen.Stat. � 72-1724 (1949). Pursuant to that authority, the Topeka Board of Education elected to establish segregated elementary schools. Other public schools in the community, however, are operated on a nonsegregated basis. The three-judge District Court, convened under 28 U.S.C. �� 2281 and 2284, found that segregation in public education has a detrimental effect upon Negro children, but denied relief on the ground that the Negro and white schools were substantially equal with respect to buildings, transportation, curricula, and educational qualifications of teachers. 98 F.Supp. 797. The case is here on direct appeal under 28 U.S.C. � 1253.

In the South Carolina case, Briggs v. Elliott, the plaintiffs are Negro children of both elementary and high school age residing in Clarendon County. They brought this action in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina to enjoin enforcement of provisions in the state constitution and statutory code which require the segregation of Negroes and whites in public schools. S.C.Const., Art. XI, � 7; S.C.Code � 5377 (1942). The three-judge District Court, convened under 28 U.S.C. �� 2281 and 2284, denied the requested relief. The court found that the Negro schools were inferior to the white schools, and ordered the defendants to begin immediately to equalize the facilities. But the court sustained the validity of the contested provisions and denied the plaintiffs admission to the white schools during the equalization program. 98 F.Supp. 529. This Court vacated the District Court's judgment and remanded the case for the purpose of obtaining the court's views on a report filed by the defendants concerning the progress made in the equalization program. 342 U.S. 350. On remand, the District Court found that substantial equality had been achieved except for buildings and that the defendants were proceeding to rectify this inequality as well. 103 F.Supp. 920. The case is again here on direct appeal under 28 U.S.C. � 1253.

In the Virginia case, Davis v. County School Board, the plaintiffs are Negro children of high school age residing in Prince Edward County. They brought this action in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia to enjoin enforcement of provisions in the state constitution and statutory code which require the segregation of Negroes and whites in public schools. Va.Const., � 140; Va.Code � 22-221 (1950). The three-judge District Court, convened under 28 U.S.C. �� 2281 and 2284, denied the requested relief. The court found the Negro school inferior in physical plant, curricula, and transportation, and ordered the defendants forthwith to provide substantially equal curricula and transportation and to "proceed with all reasonable diligence and dispatch to remove" the inequality in physical plant. But, as in the South Carolina case, the court sustained the validity of the contested provisions and denied the plaintiffs admission to the white schools during the equalization program. 103 F.Supp. 337. The case is here on direct appeal under 28 U.S.C. � 1253.

In the Delaware case, Gebhart v. Belton, the plaintiffs are Negro children of both elementary and high school age residing in New Castle County. They brought this action in the Delaware Court of Chancery to enjoin enforcement of provisions in the state constitution and statutory code which require the segregation of Negroes and whites in public schools. Del.Const., Art. X, � 2; Del.Rev.Code � 2631 (1935). The Chancellor gave judgment for the plaintiffs and ordered their immediate admission to schools previously attended only by white children, on the ground that the Negro schools were inferior with respect to teacher training, pupil-teacher ratio, extracurricular activities, physical plant, and time and distance involved in travel. 87 A.2d 862. The Chancellor also found that segregation itself results in an inferior education for Negro children (see note 10, infra), but did not rest his decision on that ground. Id. at 865. The Chancellor's decree was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Delaware, which intimated, however, that the defendants might be able to obtain a modification of the decree after equalization of the Negro and white schools had been accomplished. 91 A.2d 137, 152. The defendants, contending only that the Delaware courts had erred in ordering the immediate admission of the Negro plaintiffs to the white schools, applied to this Court for certiorari. The writ was granted, 344 U.S. 891. The plaintiffs, who were successful below, did not submit a cross-petition.

2. 344 U.S. 1, 141, 891.

3. 345 U.S. 972. The Attorney General of the United States participated both Terms as amicus curiae.

4. For a general study of the development of public education prior to the Amendment, see Butts and Cremin, A History of Education in American Culture (1953), Pts. I, II; Cubberley, Public Education in the United States (1934 ed.), cc. II-XII. School practices current at the time of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment are described in Butts and Cremin, supra, at 269-275; Cubberley, supra, at 288-339, 408-431; Knight, Public Education in the South (1922), cc. VIII, IX. See also H. Ex.Doc. No. 315, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. (1871). Although the demand for free public schools followed substantially the same pattern in both the North and the South, the development in the South did not begin to gain momentum until about 1850, some twenty years after that in the North. The reasons for the somewhat slower development in the South (e.g., the rural character of the South and the different regional attitudes toward state assistance) are well explained in Cubberley, supra, at 408-423. In the country as a whole, but particularly in the South, the War virtually stopped all progress in public education. Id. at 427-428. The low status of Negro education in all sections of the country, both before and immediately after the War, is described in Beale, A History of Freedom of Teaching in American Schools (1941), 112-132, 175-195. Compulsory school attendance laws were not generally adopted until after the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, and it was not until 1918 that such laws were in force in all the states. Cubberley, supra, at 563-565.

5. Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36, 67-72 (1873); Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 307-308 (1880): It ordains that no State shall deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law, or deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. What is this but declaring that the law in the States shall be the same for the black as for the white; that all persons, whether colored or white, shall stand equal before the laws of the States, and, in regard to the colored race, for whose protection the amendment was primarily designed, that no discrimination shall be made against them by law because of their color? The words of the amendment, it is true, are prohibitory, but they contain a necessary implication of a positive immunity, or right, most valuable to the colored race -- the right to exemption from unfriendly legislation against them distinctively as colored -- exemption from legal discriminations, implying inferiority in civil society, lessening the security of their enjoyment of the rights which others enjoy, and discriminations which are steps towards reducing them to the condition of a subject race.See also Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313, 318 (1880); Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 344-345 (1880).

6. The doctrine apparently originated in Roberts v. City of Boston, 59 Mass.198, 206 (1850), upholding school segregation against attack as being violative of a state constitutional guarantee of equality. Segregation in Boston public schools was eliminated in 1855. Mass.Acts 1855, c. 256. But elsewhere in the North, segregation in public education has persisted in some communities until recent years. It is apparent that such segregation has long been a nationwide problem, not merely one of sectional concern.

7. See also Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45 (1908).

8. In the Cummin case, Negro taxpayers sought an injunction requiring the defendant school board to discontinue the operation of a high school for white children until the board resumed operation of a high school for Negro children. Similarly, in the Gong Lum case, the plaintiff, a child of Chinese descent, contended only that state authorities had misapplied the doctrine by classifying him with Negro children and requiring him to attend a Negro school.

9. In the Kansas case, the court below found substantial equality as to all such factors. 98 F.Supp. 797, 798. In the South Carolina case, the court below found that the defendants were proceeding "promptly and in good faith to comply with the court's decree." 103 F.Supp. 920, 921. In the Virginia case, the court below noted that the equalization program was already "afoot and progressing" (103 F.Supp. 337, 341); since then, we have been advised, in the Virginia Attorney General's brief on reargument, that the program has now been completed. In the Delaware case, the court below similarly noted that the state's equalization program was well under way. 91 A.2d 137, 149.

10. A similar finding was made in the Delaware case:I conclude from the testimony that, in our Delaware society, State-imposed segregation in education itself results in the Negro children, as a class, receiving educational opportunities which are substantially inferior to those available to white children otherwise similarly situated.87 A.2d 862, 865.

11. K.B. Clark, Effect of Prejudice and Discrimination on Personality Development (Mid-century White House Conference on Children and Youth, 1950); Witmer and Kotinsky, Personality in the Making (1952), c. VI; Deutscher and Chein, The Psychological Effects of Enforced Segregation A Survey of Social Science Opinion, 26 J.Psychol. 259 (1948); Chein, What are the Psychological Effects of Segregation Under Conditions of Equal Facilities?, 3 Int.J.Opinion and Attitude Res. 229 (1949); Brameld, Educational Costs, in Discrimination and National Welfare (MacIver, ed., 1949), 44-48; Frazier, The Negro in the United States (1949), 674-681. And see generally Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944).

12. See Bolling v. Sharpe, post, p. 497, concerning the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

13.

4. Assuming it is decided that segregation in public schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment(a) would a decree necessarily follow providing that, within the limits set by normal geographic school districting, Negro children should forthwith be admitted to schools of their choice, or(b) may this Court, in the exercise of its equity powers, permit an effective gradual adjustment to be brought about from existing segregated systems to a system not based on color distinctions?5. On the assumption on which questions 4(a) and (b) are based, and assuming further that this Court will exercise its equity powers to the end described in question 4(b),(a) should this Court formulate detailed decrees in these cases;(b) if so, what specific issues should the decrees reach;(c) should this Court appoint a special master to hear evidence with a view to recommending specific terms for such decrees;(d) should this Court remand to the courts of first instance with directions to frame decrees in these cases and, if so, what general directions should the decrees of this Court include and what procedures should the courts of first instance follow in arriving at the specific terms of more detailed decrees?

14. See Rule 42, Revised Rules of this Court (effective July 1, 1954).

U.S. COURTS' HISTORY OF 'SEPARATE BUT EQUAL' AND THE FIGHT AGAINST IT LEADING TO THE BROWN DECISION.

FEDERAL COURTS

RULES & POLICIES

JUDGES & JUDGESHIPS

STATISTICS

FORMS & FEES

COURT RECORDS

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

NEWS

Home > Educational Resources > Get Involved > Federal Court Activities > Brown v. Board of Education Re-Enactment > History of Brown v. Board of Education

HISTORY OF BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION

The Plessy Decision

Although the Declaration of Independence stated that "All men are created equal," due to the institution of slavery, this statement was not to be grounded in law in the United States until after the Civil War (and, arguably, not completely fulfilled for many years thereafter). In 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified and finally put an end to slavery. Moreover, the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) strengthened the legal rights of newly freed slaves by stating, among other things, that no state shall deprive anyone of either "due process of law" or of the "equal protection of the law." Finally, the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) further strengthened the legal rights of newly freed slaves by prohibiting states from denying anyone the right to vote due to race.

Despite these Amendments, African Americans were often treated differently than whites in many parts of the country, especially in the South. In fact, many state legislatures enacted laws that led to the legally mandated segregation of the races. In other words, the laws of many states decreed that blacks and whites could not use the same public facilities, ride the same buses, attend the same schools, etc. These laws came to be known as Jim Crow laws. Although many people felt that these laws were unjust, it was not until the 1890s that they were directly challenged in court. In 1892, an African-American man named Homer Plessy refused to give up his seat to a white man on a train in New Orleans, as he was required to do by Louisiana state law. For this action he was arrested. Plessy, contending that the Louisiana law separating blacks from whites on trains violated the "equal protection clause" of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, decided to fight his arrest in court. By 1896, his case had made it all the way to the United States Supreme Court. By a vote of 8-1, the Supreme Court ruled against Plessy. In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, Justice Henry Billings Brown, writing the majority opinion, stated that:

"The object of the [Fourteenth] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to endorse social, as distinguished from political, equality. . . If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane."

The lone dissenter, Justice John Marshal Harlan, interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment another way, stated, "Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." Justice Harlan�s dissent would become a rallying cry for those in later generations that wished to declare segregation unconstitutional.

Sadly, as a result of the Plessy decision, in the early twentieth century the Supreme Court continued to uphold the legality of Jim Crow laws and other forms of racial discrimination. In the case of Cumming v. Richmond (Ga.) County Board of Education (1899), for instance, the Court refused to issue an injunction preventing a school board from spending tax money on a white high school when the same school board voted to close down a black high school for financial reasons. Moreover, in Gong Lum v. Rice (1927), the Court upheld a school�s decision to bar a person of Chinese descent from a "white" school.

The Road to Brown

(Note: Some of the case information is from Patterson, James T. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy. Oxford University Press; New York, 2001.)

Early Cases

Despite the Supreme Court's ruling in Plessy and similar cases, many people continued to press for the abolition of Jim Crow and other racially discriminatory laws. One particular organization that fought for racial equality was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) founded in 1909. For about the first 20 years of its existence, it tried to persuade Congress and other legislative bodies to enact laws that would protect African Americans from lynchings and other racist actions. Beginning in the 1930s, though, the NAACP's Legal Defense and Education Fund began to turn to the courts to try to make progress in overcoming legally sanctioned discrimination. From 1935 to 1938, the legal arm of the NAACP was headed by Charles Hamilton Houston. Houston, together with Thurgood Marshall, devised a strategy to attack Jim Crow laws by striking at them where they were perhaps weakest�in the field of education. Although Marshall played a crucial role in all of the cases listed below, Houston was the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund while Murray v. Maryland and Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada were decided. After Houston returned to private practice in 1938, Marshall became head of the Fund and used it to argue the cases of Sweat v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Regents of Higher Education.

Murray v. Maryland (1936)

Disappointed that the University of Maryland School of Law was rejecting black applicants solely because of their race, beginning in 1933 Thurgood Marshall (who was himself rejected from this law school because of its racial acceptance policies) decided to challenge this practice in the Maryland court system. Before a Baltimore City Court in 1935, Marshall argued that Donald Gaines Murray was just as qualified as white applicants to attend the University of Maryland�s School of Law and that it was solely due to his race that he was rejected. Furthermore, he argued that since the "black" law schools which Murray would otherwise have to attend were nowhere near the same academic caliber as the University�s law school, the University was violating the principle of "separate but equal." Moreover, Marshall argued that the disparities between the "white" and "black" law schools were so great that the only remedy would be to allow students like Murray to attend the University�s law school. The Baltimore City Court agreed and the University then appealed to the Maryland Court of Appeals. In 1936, the Court of Appeals also ruled in favor of Murray and ordered the law school to admit him. Two years later, Murray graduated.

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada (1938)

Beginning in 1936, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund decided to take on the case of Lloyd Gaines, a graduate student of Lincoln University (an all-black college) who applied to the University of Missouri Law School but was denied because of his race. The State of Missouri gave Gaines the option of either attending an all-black law school that it would build (Missouri did not have any all-black law schools at this time) or having Missouri help to pay for him to attend a law school in a neighboring state. Gaines rejected both of these options, and, employing the services of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, he decided to sue the state in order to attend the University of Missouri's law school. By 1938, his case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, and, in December of that year, the Court sided with him. The six-member majority stated that since a "black" law school did not currently exist in the State of Missouri, the "equal protection clause" required the state to provide, within its boundaries, a legal education for Gaines. In other words, since the state provided legal education for white students, it could not send black students, like Gaines, to school in another state.

Sweat v. Painter (1950)

Encouraged by their victory in Gaines� case, the NAACP continued to attack legally sanctioned racial discrimination in higher education. In 1946, an African American man named Heman Sweat applied to the University of Texas� "white" law school. Hoping that it would not have to admit Sweat to the "white" law school if a "black" school already existed, elsewhere on the University�s campus, the state hastily set up an underfunded "black" law school. At this point, Sweat employed the services of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and sued to be admitted to the University�s "white" law school. He argued that the education that he was receiving in the "black" law school was not of the same academic caliber as the education that he would be receiving if he attended the "white" law school. When the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1950, the Court unanimously agreed with him, citing as its reason the blatant inequalities between the University�s law school (the school for whites) and the hastily erected school for blacks. In other words, the "black" law school was "separate," but not "equal." Like the Murray case, the Court found the only appropriate remedy for this situation was to admit Sweat to the University�s law school.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Regents of Higher Education (1950)

In 1949, the University of Oklahoma admitted George McLaurin, an African American, to its doctoral program. However, it required him to sit apart from the rest of his class, eat at a separate time and table from white students, etc. McLaurin, stating that these actions were both unusual and resulting in adverse effects on his academic pursuits, sued to put an end to these practices. McLaurin employed Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund to argue his case, a case which eventually went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In an opinion delivered on the same day as the decision in Sweat, the Court stated that the University�s actions concerning McLaurin were adversely affecting his ability to learn and ordered that they cease immediately.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954, 1955)

The case that came to be known as Brown v. Board of Education was actually the name given to five separate cases that were heard by the U.S. Supreme Court concerning the issue of segregation in public schools. These cases were Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Briggs v. Elliot, Davis v. Board of Education of Prince Edward County (VA.), Boiling v. Sharpe, and Gebhart v. Ethel. While the facts of each case are different, the main issue in each was the constitutionality of state-sponsored segregation in public schools. Once again, Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund handled these cases.

Although it acknowledged some of the plaintiffs�/plaintiffs claims, a three-judge panel at the U.S. District Court that heard the cases ruled in favor of the school boards. The plaintiffs then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

When the cases came before the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court consolidated all five cases under the name of Brown v. Board of Education. Marshall personally argued the case before the Court. Although he raised a variety of legal issues on appeal, the most common one was that separate school systems for blacks and whites were inherently unequal, and thus violate the "equal protection clause" of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Furthermore, relying on sociological tests, such as the one performed by social scientist Kenneth Clark, and other data, he also argued that segregated school systems had a tendency to make black children feel inferior to white children, and thus such a system should not be legally permissible.

Meeting to decide the case, the Justices of the Supreme Court realized that they were deeply divided over the issues raised. While most wanted to reverse Plessy and declare segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional, they had various reasons for doing so. Unable to come to a solution by June 1953 (the end of the Court's 1952-1953 term), the Court decided to rehear the case in December 1953. During the intervening months, however, Chief Justice Fred Vinson died and was replaced by Gov. Earl Warren of California. After the case was reheard in 1953, Chief Justice Warren was able to do something that his predecessor had not�i.e. bring all of the Justices to agree to support a unanimous decision declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. On May 14, 1954, he delivered the opinion of the Court, stating that "We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of �separate but equal� has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. . ."

Expecting opposition to its ruling, especially in the southern states, the Supreme Court did not immediately try to give direction for the implementation of its ruling. Rather, it asked the attorney generals of all states with laws permitting segregation in their public schools to submit plans for how to proceed with desegregation. After still more hearings before the Court concerning the matter of desegregation, on May 31, 1955, the Justices handed down a plan for how it was to proceed; desegregation was to proceed with "all deliberate speed." Although it would be many years before all segregated school systems were to be desegregated, Brown and Brown II (as the Courts plan for how to desegregate schools came to be called) were responsible for getting the process underway.