MEDIA WATCH: The Memories Return: Government Spying Redux as New York Times reports on how the public learned of COINTELPRO, FBI spying on dissidents, including Martin Luther King Jr.

On the front page of the New York Times on Tuesday, January 7, 2014, there was an important article: several people who had liberated FBI documents that contained details on domestic spying against the �New Left� � the anti-Vietnam War, peace, Black Power, Women�s Liberation, gay and lesbian movements � had finally �surfaced� themselves. Accompanying this article was a 15 minute video, which can be found at http://www.nytimes.com/video/us/100000002635482/stealing-j-edgar-hoovers-secrets.html.

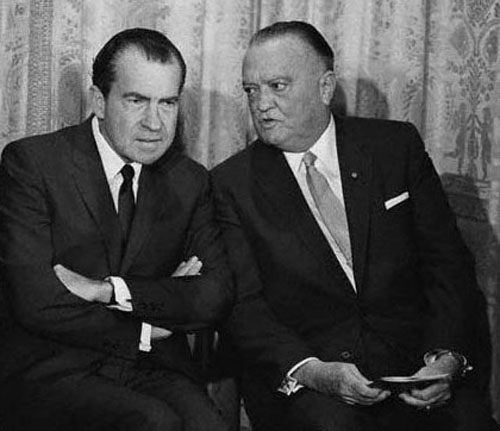

Richard M. Nixon (left) was President while J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, carried out COINTELPRO against dissidents ranging from civil rights leaders and union activists to anti-war protesters.The story is important. While the �movement� had long suspected that the FBI, Army intelligence (I know � an oxymoron) and other repressive agencies had infiltrated their organizations and participated detrimentally in their activities, there was no �proof.� The raid on the FBI office in Media, PA, a suburb of Philadelphia, changed all that: activists got the proof, and in the FBI�s own �handwriting.�

Richard M. Nixon (left) was President while J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, carried out COINTELPRO against dissidents ranging from civil rights leaders and union activists to anti-war protesters.The story is important. While the �movement� had long suspected that the FBI, Army intelligence (I know � an oxymoron) and other repressive agencies had infiltrated their organizations and participated detrimentally in their activities, there was no �proof.� The raid on the FBI office in Media, PA, a suburb of Philadelphia, changed all that: activists got the proof, and in the FBI�s own �handwriting.�

A group of eight people � originally nine, but one backed out � decided they would try to get into this FBI office in an effort to see if they could obtain official documents proving their suspicions. On March 8, 1971 � when almost the entire nation was watching a heavy-weight boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier � they �did the deed.� The FBI never caught them.

Their findings were explosive, although the biggest �bang� only came later. They found many �smoking guns,� including memos from J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the FBI, telling agents to increase paranoia and disrupt the Left. Hoover had sent out a memo in 1970, urging agents to step-up their interviews and activities vis-�-vis the movement. �It will enhance the paranoia endemic in these circles and will further serve to get the point across there is an FBI agent behind every mailbox,� according to one memo cited in the Times article by Mark Mazzetti. Also, according to Mazzetti, �Another document, signed by Hoover himself, revealed widespread FBI surveillance of black student groups on college campuses.�

Using the name �Citizens� Committee to Investigate the FBI,� the activists gathered the evidence, copied it and mailed it to journalists and newspapers around the country; most importantly to Betty Medsger, who wrote for the Washington Post. Despite pressure on the Post hierarchy from the Nixon Administration, including the US Attorney General, John Mitchell, Ms. Medsger wrote the first story on the break-in. The New York Times and others soon followed.

Ms. Medsger�s new book, THE BURGLARY: THE DISCOVERY OF J. EDGAR HOOVER�S SECRET FBI will be published soon, and she convinced five of the eight people to reveal their identities for the first time: William C. Davidon, who died last year; Keith Forsyth, Bonnie Raines, Bonnie Raines, and Bob Williamson. These people risked many years in prison had they been caught, yet the felt the risk of finding and revealing FBI illegal activities was worth the risk.

The biggest �bang� took some time to develop. The activists found a term in the cache of documents they had liberated that was labeled �COINTELPRO,� but didn�t know what it meant. Years later, NBC reporter Carl Stern got files from the FBI that revealed the scope of the Counter Intelligence Program. According to Mazzetti, �Since 1956, the FBI had carried out an expansive campaign to spy on civil rights leaders, political organizers and suspect Communists, and had tried to sow distrust among protest groups. Among the grim litany of revelations was a blackmail letter FBI agents had sent anonymously to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., threatening to expose his extramarital affairs if he did not commit suicide.�

One of the most prolific agents of the Chicago Police Red Squad was Otis Elementary School teacher Sheli Lulkin (above right), whose spying was first reported in Substance in June 1976. Lulkin spied on groups ranging from dissident union leaders and civil rights people to the Black Panthers and Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). Her confidential reports to the Red Squad were characterized by the kind of gossip, especially sexual gossip, that J. Edgar Hoover tried to use to blackmail dissidents, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. At the time she was spying, Lulkin was part of the leadership of both the CTU and the national American Federation of Teachers (AFT), where she was co-chair of the AFT Women's Rights Committee.[One thing that later came out about COINTELPRO was that the Nixon Administration had a secret plan, code named GARDEN PLOT, which would have sent the Army and National Guard into American cities to control protesters.This differs from the �ordinary� control by State Governors; it was to be approved by the President of the United States.]

One of the most prolific agents of the Chicago Police Red Squad was Otis Elementary School teacher Sheli Lulkin (above right), whose spying was first reported in Substance in June 1976. Lulkin spied on groups ranging from dissident union leaders and civil rights people to the Black Panthers and Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). Her confidential reports to the Red Squad were characterized by the kind of gossip, especially sexual gossip, that J. Edgar Hoover tried to use to blackmail dissidents, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. At the time she was spying, Lulkin was part of the leadership of both the CTU and the national American Federation of Teachers (AFT), where she was co-chair of the AFT Women's Rights Committee.[One thing that later came out about COINTELPRO was that the Nixon Administration had a secret plan, code named GARDEN PLOT, which would have sent the Army and National Guard into American cities to control protesters.This differs from the �ordinary� control by State Governors; it was to be approved by the President of the United States.]

The analogies to efforts by Edward Snowden to expose NSA (National Security Agency) malfeance are all too obvious, although the risks taken by the 1971 activists, who were outside of the targeted agency, would seem to have been much greater. Nonetheless, John and Bonnie Raines said, �They felt a kinship toward Mr. Snowden, whose revelations about NSA spying they see as a bookend to their own disclosures so long ago,� wrote Mazzotti.

Yet making these connections is not enough. We have to remember the work of the Chicago Red Squad and it�s work against the movement. Two cases stand out: one was a teacher, Sheli Lulkin, who was used to infiltrate the local chapter of Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) and who reported on groups ranging from Civil Rights groups to the Chicago Teachers Union is dozens of reports. Lulkin's spying on VVAW was revealed by Substance in June 1976.

The VVAW spying alone was massive: Over 21,000 pages of documents of FBI surveillance of VVAW are now on-line at http://www.wintersoldier.com/index.php?topic=VVAWFBI , placed there by the Swift Boat veterans who assailed John Kerry�s war record in 2004.

Chicago was one of the most important targets of FBI (and other government agencies') spying. Some of it turned deadly. One case was the assassination of Chicago Black Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in Chicago on December 5, 1969 by the "State's Attorney's Police" under the command of then Cook County State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan. According to the book, "The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther" by Jeffrey Hass (2011), the FBI had infiltrated Hampton�s security detail. It turned out that not only did the police have a drawing of the apartment in which Hampton, his partner, and Mark Clark were staying -- with specific attention to the location of Hampton � but they had their informant drug Hampton before the police raid. Over 90 bullets struck Hampton during the raid, although his pregnant girlfriend lying next to him was not hit. At first Chicago's corporate media reported the story as a "shoot out" between the Panthers and the State's Attorney's Police. But careful reporting by Lu Palmer, who at the time was writing for the Chicago Daily News, revealed that all of the bullets in Fred Hampton's bedroom were heading in one direction: Hampton was murdered in a hail of bullets, not killed on a melodramatic shootout.

Less dramatic and dangerous was the routine spying against most people active in the "movement." Substance editor George Schmidt was active in the mobilization demonstrations against the Vietnam War in August 1968, where he had tried to serve as a marshall. "At the time I was a University of Chicago student," Schmidt told me. "I also had to work a job, and was working for the Chicago Osteopathic Medical Center as a clerk. One Saturday morning I arrived at work and there were two middle aged white guys in suits sitting among all the black people in the waiting room. When I began my work at the cash register, my boss passed me a note that read: 'FBI!' and then he pointed at the two white guys. 'They want to talk with you,' he whispered and ordered me to go to the cafeteria and talk with the agents. They asked questions about the Democratic Convention demonstrations. We had been told never to talk with the FBI, but we were still young..."

Schmidt said that he almost lost his off-campus job as a result of the FBI visit that morning. "Looking back, it's clearly an example of the kind of fear-spreading that the Media papers later revealed," he says. "I was a minor activist during the 1968 convention, and it's clear that the reason for that visit of those two white guys in that waiting room full of poor black people was to cost me my job -- or at least intimidate me. It didn't work, but no one knows how many thousands of times they did stuff like that..."

Hundreds of Chicago teachers, veterans, anti-war, union leaders, and civil rights activists were named in the documents uncovered during Red Squad litigation in reports by Sheli Lulkin alone. And she was just one of many police spies infiltrating or trying to infiltrate "the movement," according to George Schmidt. Many others also have memories of those days...

The activities of the FBI, the NSA, the Chicago Red Squad, etc., are all efforts to keep Americans under control. If the activities of our �leaders� were so repugnant � in Chicago and around the world � why would they need this control?

"I hope that everyone will read the latest story from The New York Times, and the book. For now, the video that The New York Times has put on its website will help," said George Schmidt. Everyone should go to: http://www.nytimes.com/video/us/100000002635482/stealing-j-edgar-hoovers-secrets.html.

[Kim Scipes is Chair of the Chicago Chapter of the National Writers Union, UAW #1981.]

NEW YORK TIMES STORY FROM JANUARY 7, 2014:

Burglars who took on FBI abandon shadows

PHILADELPHIA � The perfect crime is far easier to pull off when nobody is watching.

So on a night nearly 43 years ago, while Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier bludgeoned each other over 15 rounds in a televised title bout viewed by millions around the world, burglars took a lock pick and a crowbar and broke into a Federal Bureau of Investigation office in a suburb of Philadelphia, making off with nearly every document inside.

They were never caught, and the stolen documents that they mailed anonymously to newspaper reporters were the first trickle of what would become a flood of revelations about extensive spying and dirty-tricks operations by the F.B.I. against dissident groups.

The burglary in Media, Pa., on March 8, 1971, is a historical echo today, as disclosures by the former National Security Agency contractor Edward J. Snowden have cast another unflattering light on government spying and opened a national debate about the proper limits of government surveillance. The burglars had, until now, maintained a vow of silence about their roles in the operation. They were content in knowing that their actions had dealt the first significant blow to an institution that had amassed enormous power and prestige during J. Edgar Hoover�s lengthy tenure as director.

�When you talked to people outside the movement about what the F.B.I. was doing, nobody wanted to believe it,� said one of the burglars, Keith Forsyth, who is finally going public about his involvement. �There was only one way to convince people that it was true, and that was to get it in their handwriting.�

Mr. Forsyth, now 63, and other members of the group can no longer be prosecuted for what happened that night, and they agreed to be interviewed before the release this week of a book written by one of the first journalists to receive the stolen documents. The author, Betty Medsger, a former reporter for The Washington Post, spent years sifting through the F.B.I.�s voluminous case file on the episode and persuaded five of the eight men and women who participated in the break-in to end their silence.

Unlike Mr. Snowden, who downloaded hundreds of thousands of digital N.S.A. files onto computer hard drives, the Media burglars did their work the 20th-century way: they cased the F.B.I. office for months, wore gloves as they packed the papers into suitcases, and loaded the suitcases into getaway cars. When the operation was over, they dispersed. Some remained committed to antiwar causes, while others, like John and Bonnie Raines, decided that the risky burglary would be their final act of protest against the Vietnam War and other government actions before they moved on with their lives.

�We didn�t need attention, because we had done what needed to be done,� said Mr. Raines, 80, who had, with his wife, arranged for family members to raise the couple�s three children if they were sent to prison. �The �60s were over. We didn�t have to hold on to what we did back then.�

A Meticulous Plan

Keith Forsyth, in the early 1970s, was the designated lock-picker among the eight burglars. When he found that he could not pick the lock on the front door of the F.B.I. office, he broke in through a side entrance.

The burglary was the idea of William C. Davidon, a professor of physics at Haverford College and a fixture of antiwar protests in Philadelphia, a city that by the early 1970s had become a white-hot center of the peace movement. Mr. Davidon was frustrated that years of organized demonstrations seemed to have had little impact.

In the summer of 1970, months after President Richard M. Nixon announced the United States� invasion of Cambodia, Mr. Davidon began assembling a team from a group of activists whose commitment and discretion he had come to trust.

The group � originally nine, before one member dropped out � concluded that it would be too risky to try to break into the F.B.I. office in downtown Philadelphia, where security was tight. They soon settled on the bureau�s satellite office in Media, in an apartment building across the street from the county courthouse.

That decision carried its own risks: Nobody could be certain whether the satellite office would have any documents about the F.B.I.�s surveillance of war protesters, or whether a security alarm would trip as soon as the burglars opened the door.

The group spent months casing the building, driving past it at all times of the night and memorizing the routines of its residents.

�We knew when people came home from work, when their lights went out, when they went to bed, when they woke up in the morning,� said Mr. Raines, who was a professor of religion at Temple University at the time. �We were quite certain that we understood the nightly activities in and around that building.�

But it wasn�t until Ms. Raines got inside the office that the group grew confident that it did not have a security system. Weeks before the burglary, she visited the office posing as a Swarthmore College student researching job opportunities for women at the F.B.I.

The burglary itself went off largely without a hitch, except for when Mr. Forsyth, the designated lock-picker, had to break into a different entrance than planned when he discovered that the F.B.I. had installed a lock on the main door that he could not pick. He used a crowbar to break the second lock, a deadbolt above the doorknob.

After packing the documents into suitcases, the burglars piled into getaway cars and rendezvoused at a farmhouse to sort through what they had stolen. To their relief, they soon discovered that the bulk of it was hard evidence of the F.B.I.�s spying on political groups. Identifying themselves as the Citizens� Commission to Investigate the F.B.I., the burglars sent select documents to several newspaper reporters. Two weeks after the burglary, Ms. Medsger wrote the first article based on the files, after the Nixon administration tried unsuccessfully to get The Post to return the documents.

Other news organizations that had received the documents, including The New York Times, followed with their own reports.

At The Washington Post, Betty Medsger was the first to report on the contents of the stolen F.B.I. files. Now, she has written a book about the episode. Robert Caplin for The New York Times

Ms. Medsger�s article cited what was perhaps the most damning document from the cache, a 1970 memorandum that offered a glimpse into Hoover�s obsession with snuffing out dissent. The document urged agents to step up their interviews of antiwar activists and members of dissident student groups.

�It will enhance the paranoia endemic in these circles and will further serve to get the point across there is an F.B.I. agent behind every mailbox,� the message from F.B.I. headquarters said. Another document, signed by Hoover himself, revealed widespread F.B.I. surveillance of black student groups on college campuses.

But the document that would have the biggest impact on reining in the F.B.I.�s domestic spying activities was an internal routing slip, dated 1968, bearing a mysterious word: Cointelpro.

Neither the Media burglars nor the reporters who received the documents understood the meaning of the term, and it was not until several years later, when the NBC News reporter Carl Stern obtained more files from the F.B.I. under the Freedom of Information Act, that the contours of Cointelpro � shorthand for Counterintelligence Program � were revealed.

Since 1956, the F.B.I. had carried out an expansive campaign to spy on civil rights leaders, political organizers and suspected Communists, and had tried to sow distrust among protest groups. Among the grim litany of revelations was a blackmail letter F.B.I. agents had sent anonymously to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., threatening to expose his extramarital affairs if he did not commit suicide.

The F.B.I. field office in Media, Pa., from which the burglars stole files that showed the extent of the bureau�s surveillance of political groups. Betty Medsger

�It wasn�t just spying on Americans,� said Loch K. Johnson, a professor of public and international affairs at the University of Georgia who was an aide to Senator Frank Church, Democrat of Idaho. �The intent of Cointelpro was to destroy lives and ruin reputations.�

Senator Church�s investigation in the mid-1970s revealed still more about the extent of decades of F.B.I. abuses, and led to greater congressional oversight of the F.B.I. and other American intelligence agencies. The Church Committee�s final report about the domestic surveillance was blunt. �Too many people have been spied upon by too many government agencies, and too much information has been collected,� it read.

By the time the committee released its report, Hoover was dead and the empire he had built at the F.B.I. was being steadily dismantled. The roughly 200 agents he had assigned to investigate the Media burglary came back empty-handed, and the F.B.I. closed the case on March 11, 1976 � three days after the statute of limitations for burglary charges had expired.

Michael P. Kortan, a spokesman for the F.B.I., said that �a number of events during that era, including the Media burglary, contributed to changes to how the F.B.I. identified and addressed domestic security threats, leading to reform of the F.B.I.�s intelligence policies and practices and the creation of investigative guidelines by the Department of Justice.�

According to Ms. Medsger�s book, �The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover�s Secret F.B.I.,� only one of the burglars was on the F.B.I.�s final list of possible suspects before the case was closed.

Afterward, they fled to a farmhouse, near Pottstown, Pa., where they spent 10 days sorting through the documents. Betty Medsger

A Retreat Into Silence

The eight burglars rarely spoke to one another while the F.B.I. investigation was proceeding and never again met as a group.

Mr. Davidon died late last year from complications of Parkinson�s disease. He had planned to speak publicly about his role in the break-in, but three of the burglars have chosen to remain anonymous.

Among those who have come forward � Mr. Forsyth, the Raineses and a man named Bob Williamson � there is some wariness of how their decision will be viewed.

The passage of years has worn some of the edges off the once radical political views of John and Bonnie Raines. But they said they felt a kinship toward Mr. Snowden, whose revelations about N.S.A. spying they see as a bookend to their own disclosures so long ago.

They know some people will criticize them for having taken part in something that, if they had been caught and convicted, might have separated them from their children for years. But they insist they would never have joined the team of burglars had they not been convinced they would get away with it.

�It looks like we�re terribly reckless people,� Mr. Raines said. �But there was absolutely no one in Washington � senators, congressmen, even the president � who dared hold J. Edgar Hoover to accountability.�

�It became pretty obvious to us,� he said, �that if we don�t do it, nobody will.�

The Retro Report video with this article is the 24th in a documentary series presented by The New York Times. The video project was started with a grant from Christopher Buck. Retro Report has a staff of 13 journalists and 10 contributors led by Kyra Darnton, a former �60 Minutes� producer. It is a nonprofit video news organization that aims to provide a thoughtful counterweight to today�s 24/7 news cycle.

A version of this article appears in print on January 7, 2014, on page A1 of the New York edition with the headline: Burglars Who Took On F.B.I. Abandon Shadows.

GLEN GREENWALK, WHO REPORTED EDWARD SNOWDEN'S REVELATIOINS, WROTE ABOUT THE LATEST:

Glenn Greenwald. January 7, 2014. Greenwald Side Docs

It's easy to praise people who challenge governments of the distant past, and much harder to do so for those who challenge those who wield actual power today.

The New York Times this morning (JANUARY 7, 2014) has an extraordinary 13-minute video from a team of reporters including the independent journalist Jonathan Franklin, and an accompanying article by Mark Mazzetti, about the heroic anti-war activists who broke into an FBI field office in 1971 and took all of the documents they could get their hands on, and then sent those documents to newspapers, including the New York Times and Washington Post.

Some of those documents exposed J. Edgar Hoover's COINTELPRO program, aimed at quashing internal political dissent through surveillance, infiltration and other tactics. Those revelations ultimately led to the creation of the Church Committee in the mid-1970s and various reforms. The background on the Church Committee's COINTELPRO findings and the "burglary" operation which exposed it is here.

With the statute of limitations elapsed on their "crimes", ones the FBI could never solve, the courageous perpetrators have now unveiled themselves. The NYT story is based on a new book by Post reporter Betsy Medsger and the forthcoming documentary 1971 (of which my journalistic partner, Laura Poitras, is an Exective Producer). There are four crucial points to note:

(1) Just as is true of Daniel Ellsberg today, these activists will be widely hailed as heroic, noble, courageous, etc. That's because it's incredibly easy to praise people who challenge governments of the distant past, and much harder to do so for those who challenge those who wield actual power today.

As you watch the video, just imagine what today's American commentariat, media class, and establishment figures from both parties would be saying in denouncing these activists. They stole government documents that didn't belong to them! They endangered national security! They did not take just a few documents but everything en masse that they could get their hands on. Former FBI and CIA chief William Webster is shown in the film conceding that the documents they revealed led to important debates, but nonetheless condemning them on the grounds that they used the "wrong methods" - criminal methods! - to expose these bad acts, insisting that they should have gone through unspecified Proper Channels.

That all sounds quite familiar, does it not? Many of the journalists and pundits who today will praise these activists would have undoubtedly been leading the orgy of condemnations against them back then based on the same things they say today.

(2) The crux of COINTELPRO - targeting citizens for their disfavored political views and trying to turn them into criminals through infiltration, entrapment and the like - is alive and well today in the United States. Those tactics are no longer called COINTELPRO; they are called "anticipatory prosecutions" and FBI entrapment. The targets are usually American Muslims but also a wide range of political activists. See here for how vibrant these COINTELPRO-like tactics remain today.

(3) The activists sent the FBI's documents they took to various newspapers. While the Post published articles based on them (after lengthy internal debates about whether they should), the other papers, as Trevor Timm documents, "were not nearly as admirable." In particular:

According to Medsger�s book, even though the New York Times eventually published a story based on the documents, a reporter of theirs apparently handed the documents back to the FBI to help with their investigation. And the Los Angeles Times, never published any story and may have also handed the documents back to the FBI.

Moreover, the U.S. Government exhibited zero interest in investigating and prosecuting the lawbreakers inside the FBI. Instead, they became obsessed only with punishing those who exposed the high-level wrongdoing. This, too, obviously should sound very familiar.

(4) The parallels with the 1971 whistleblowers and those of today, including Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning, are obvious. One of the 1971 activists makes the point expressly, saying "I definitely see parallels between Snowden's case and our case" and pronouncing Snowden's disclosure of NSA documents to be "a good thing". Another of the activists, John Raines, makes the parallel even clearer:

"It looks like we�re terribly reckless people," Mr. Raines said. "But there was absolutely no one in Washington � senators, congressmen, even the president � who dared hold J. Edgar Hoover to accountability."

"It became pretty obvious to us", he said, "that if we don�t do it, nobody will.�

Medsger herself this morning noted the parallels, saying on Twitter that she hopes that her book "contributes to the discussion" started by Snowden's whistleblowing. The lesson, as she put it: "we've been there before."

Note, too, that these activists didn't turn themselves in and plead to be put in prison by the U.S. Government for decades, but instead purposely did everything possible to avoid arrest. Only the most irrational among us would claim that doing this somehow diluted their bravery or status as noble whistleblowers.

Here again we find another example of that vital though oft-overlooked principle: often, those labelled "criminals" by an unjust society are in fact its most noble actors.

[Glenn Greenwald is a columnist on civil liberties and US national security issues for the Guardian. A former constitutional lawyer, he was until 2012 a contributing writer at Salon. His most recent book is, With Liberty and Justice for Some: How the Law Is Used to Destroy Equality and Protect the Powerful. His other books include: Great American Hypocrites: Toppling the Big Myths of Republican Politics, A Tragic Legacy: How a Good vs. Evil Mentality Destroyed the Bush Presidency, and How Would a Patriot Act? Defending American Values from a President Run Amok. He is the recipient of the first annual I.F. Stone Award for Independent Journalism.]