'Noah Webster Academy ... nothing but a clever scheme to get public money for children who are already being educated by their parents -- at home...'Al Shanker broke with the so-called 'Charter School Movement' by 1994 after learning the early examples of charter school corruption

During the early years of America's so-called "Charter School Movement," one of the movements most important supporters was Albert Shanker, President of the American Federation of Teachers. Shanker, who had taken some of the criticisms of public schools from the controversial 1983 federal report "A Nation at Risk" to heart, became an early proponent of charter schools. During the 1980s and early 1990s, Shanker's weekly column in The New York Times 'News of the Week in Review' section was one of the most widely read advertisements in the Sunday Times. (The column was a paid advertisement and became the only ad that was indexed by The Times).

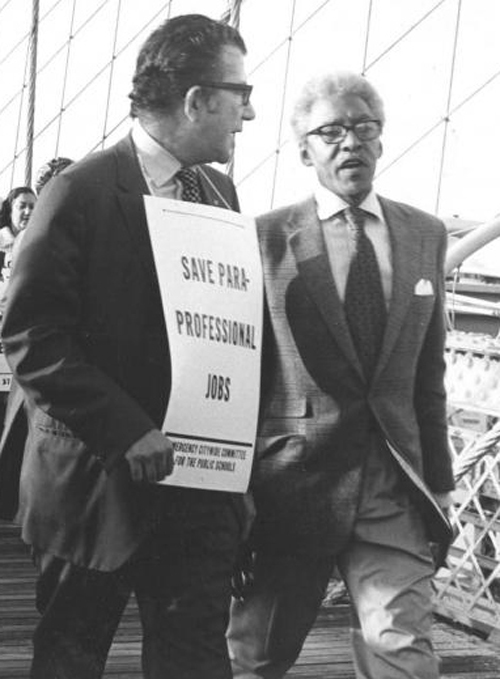

United Federation of Teachers President Albert Shanker (left) with civil rights leaders Bayard Rustin (right) crossing the Brooklyn Bridge during one of the UFT's actions for public education in New York.But one of the feature characteristics of Shanker's "Where We Stand" was that his reporting was always solid, his research fiercely accurate.

United Federation of Teachers President Albert Shanker (left) with civil rights leaders Bayard Rustin (right) crossing the Brooklyn Bridge during one of the UFT's actions for public education in New York.But one of the feature characteristics of Shanker's "Where We Stand" was that his reporting was always solid, his research fiercely accurate.

So, by 1994 Shanker had become an opponent of charter schools, and the reasons were simple: corruption and the budding anti-unionism. In one of his "Where We Stand" columns, Shanker discussed how "Noah Webster Academy" in Michigan was simply a ploy to grab public funds at the expense of a local school district.

Thanks to Diane Ravitch's blog for the following reprint of Shanker's 1994 "Where We Stand" which began to detail the AFT president's opposition to charters.

Ravitch's report: In 1993 and 1994, Albert Shanker turned against his own idea: charter schools.

Once an avid proponent, he became convinced that they would become a vehicle for privatization. Here is one of his columns reflecting his disillusionment with what had been his own creation:

Where We Stand, by Albert Shanker, President, American Federation of Teachers, NEW YORK TIMES � July 3, 1994

Noah Webster Academy. $4 million - for starters - will be going to a group of people who are eager for public funds but could care less about public education. A key idea behind charter schools, the latest movement in education reform, is that many terrific opportunities to improve public education are lost because they are squelched by school bureaucracies.

Charter school laws, which have been passed in 12 states and are pending in 9 or 10 more, are supposed to allow teachers and others the chance to establish public schools that are largely independent of state and local control. Supporters say that throwing away the rule book will unleash creativity and that the fresh, new ideas developed in these charter schools will revitalize all public schools. But it�s not so easy to draw the line between encouraging schools that have the freedom to experiment and ones where doing your own thing has nothing to do with improving public education.

This problem is already obvious in Michigan. Charter school legislation goes into effect this fall, and the first �school� out of the gate will be the Noah Webster Academy, which is nothing but a clever scheme to get public money for children who are already being educated by their parents - at home.

According to reporter Steve Stecklow�s story in the Wall Street Journal (June 14, 1994), Noah Webster�s founder, a lawyer specializing in home schooling cases, has signed up 700 students - mostly Christian home schoolers -- for a school that is actually a computer network. The students will continue to study at home the way they do now, but every family will get a taxpayer-paid computer, printer and modem, and there will be an optional curriculum that teaches creationism alongside biology.

Does this actually fall within the Michigan charter school law? Barely. Stecklow quotes a Michigan state administrator who says it is � push[ ing] the envelope...just about as far as you probably can.� Critics had predicted that something like this would happen, and the response was that charters would be issued by school boards or colleges and they could be trusted to be responsible.

But Noah Webster�s founder discovered a tiny, impoverished school district -- it has 23 students, one teacher and a teacher�s aide, and it nearly went broke a few years ago. It agreed to sponsor his school, and give it a 99-year charter, in return for a kickback of about $40,000. Based on current applications, Noah Webster, which is eligible for state funds to the tune of $5,500 per pupil, will get something in the neighborhood of $4 million of public money in the coming academic year.

Last year, Michigan suffered a big educational and financial crisis when the state decided to stop using property taxes to pay for education and had to scramble for other ways of financing its schools. The previous system gave a big advantage to wealthy districts, and the new one has provided some measure of equalization between wealthy districts and poor ones. Nevertheless, kids in wealthy districts are still getting more public money spent on them than kids in cities like Detroit. And now, the charter school law, which is supposed to be about using public money to test ideas that could improve education is troubled schools districts like...

New York Times - July 3, 1994