The union-busting billionaires behind phony 'grass roots' groups like Stand for Children and Advance Illinois have emerged from the shadows... Complete transcript of the remarks of Ross Wiener, James Crown and Jonah Edelman at the Aspen Institute

Before going into the full transcript of the Aspen Institute session with James Crown and Jonah Edelmen, one of the things that Substance staff and readers noted was that a mere two years after the Aspen Institute was praising the "Chicago Miracle" following the appointment of Arne Duncan as U.S. Secretary of Education, the Aspen Institute was trashing Chicago. Both the introduction to Jonah Edelman's remarks by billionaire James Crown and the tales told by Stand for Children's Jonah Edelman place the current "crisis" in Chicago in one of those IF WE DON'T DO SOMETHING IMMEDIATELY EVERYTHING WILL BE WORSE FOR THE CHILDREN narratives we've been hearing for ten or thirty years.

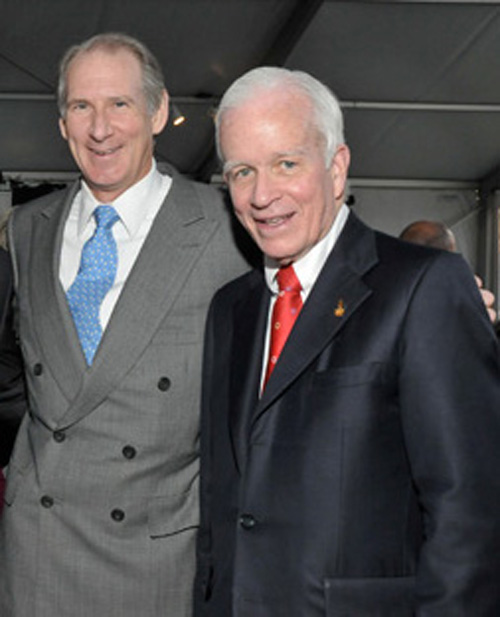

James Crown (above left) introduced Jonah Edelman to the July 2011 session at the Aspen Institute discussing how the enormous wealth of Crown and his friends was able to buy the legislation pushed through the Illinois General Assembly known as "SB7." Above, Crown stands with Andy McKenna in a recent photograph. James Crown and Andy McKenna (above right) have long been two of the wealthiest and most powerful men in Chicago. Crown's inherited wealth has made him one of Chicago's billionaires, while McKenna's "Horatio Alger" story which saw him rise from a South Side of Chicago boyhood to chairman of McDonald's Corporation (among other things) has made him the kind of person who insists that bootstrapping is possible for everyone. Both Crown and McKenna have tried to force corporate "education reform" on Chicago, Crown by bankrolling outfits like Stand for Children (and getting his friends to do likewise, with checks in the five and six figures to the group), while McKenna as President of Chicago's Commercial Club (of which the infamous Civic Committee of the Commercial Club is a part) has pushed projects ranging from "Renaissance 2010" to charter schools on Chicago's public school system. Both men are famed for their opposition to democratic unions representing working people.The July 2009 video is now available at Substance. The July 2011 video is transcribed here and still available through certain links, even though after a lot of people got interested in Edelman and Crown's latest version of Chicago, the link through the Aspen Institute Web Site went as dead as Mayor Daley's version of school reform now is in Chicago. (Chicago's new mayor, Rahm Emanuel, has been denouncing the "status quo" since he was elected with Daley's help; and there is nothing that happened in Chicago's schools between 1995, when Daley took over, and 2011, when Emanuel was elected to succeed Daley, that wasn't part of the Daley brand. But now that was then, this is now, and a new crisis has been declared by the billionaires and their lackies so that Chicago's schools can once again be reformed.

James Crown (above left) introduced Jonah Edelman to the July 2011 session at the Aspen Institute discussing how the enormous wealth of Crown and his friends was able to buy the legislation pushed through the Illinois General Assembly known as "SB7." Above, Crown stands with Andy McKenna in a recent photograph. James Crown and Andy McKenna (above right) have long been two of the wealthiest and most powerful men in Chicago. Crown's inherited wealth has made him one of Chicago's billionaires, while McKenna's "Horatio Alger" story which saw him rise from a South Side of Chicago boyhood to chairman of McDonald's Corporation (among other things) has made him the kind of person who insists that bootstrapping is possible for everyone. Both Crown and McKenna have tried to force corporate "education reform" on Chicago, Crown by bankrolling outfits like Stand for Children (and getting his friends to do likewise, with checks in the five and six figures to the group), while McKenna as President of Chicago's Commercial Club (of which the infamous Civic Committee of the Commercial Club is a part) has pushed projects ranging from "Renaissance 2010" to charter schools on Chicago's public school system. Both men are famed for their opposition to democratic unions representing working people.The July 2009 video is now available at Substance. The July 2011 video is transcribed here and still available through certain links, even though after a lot of people got interested in Edelman and Crown's latest version of Chicago, the link through the Aspen Institute Web Site went as dead as Mayor Daley's version of school reform now is in Chicago. (Chicago's new mayor, Rahm Emanuel, has been denouncing the "status quo" since he was elected with Daley's help; and there is nothing that happened in Chicago's schools between 1995, when Daley took over, and 2011, when Emanuel was elected to succeed Daley, that wasn't part of the Daley brand. But now that was then, this is now, and a new crisis has been declared by the billionaires and their lackies so that Chicago's schools can once again be reformed.

Thanks for a very hard working friend for the following transcription. Substance has also requested the official version from the Aspen Institute, but Ross Wiener hasn't returned our phone calls.

TRANSCRIPT OF VIDEO: "If It Can Happen There, It Can Happen Anywhere: Transformational Education Legislation in Illinois" Major education reforms were passed in Illinois this spring, paving the way for Chicago's new mayor, Rahm Emanuel, to enact significant changes to the Chicago Public Schools, the third largest school system in the country. Jonah Edelman and James Schine Crown discuss. Education Nation // Jun. 30, 2011 // 1:40 AM

http://www.educationnation.com/index.cfm?objectid=12F0D706-A2EC-11E0- 8C49000C296BA163

James Crown made the initial calls in September 2010 to raise the first million dollars so that "Stand for Children" could invest in Illinois politicians prior to the November 2, 2010 election. Although not all of the Stand for Children candidates won, the organization's ability to make large six-figure contributions to Illinois politicians bought access to Illinois political leaders, including House Speaker Michael Madigan. Because of the Stand for Children influence, Madigan sidestepped the Illinois General Assembly's education committee and created a new "School Reform Committee" of the Illinois House of Representatives, and installed Republican Roger Eddy and Democrat Linda Chapa La Via as co-chairs of the committee. Both Eddy and Chapa La Via were fiercely prejudiced against the Chicago Teachers Union and uncritically accepted the lurid testimony of Stand for Children and Advance Illinois during the two days of hearings on "reform" staged in Aurora on December 16 and 17 2010.ROSS WEINER. Welcome, IŌĆÖm Ross Weiner, Executive Director of the Aspen InstituteŌĆÖs Education and Society program, and IŌĆÖm just going to, uh, introduce this session very briefly, and turn it over to Jim and Jonah.

James Crown made the initial calls in September 2010 to raise the first million dollars so that "Stand for Children" could invest in Illinois politicians prior to the November 2, 2010 election. Although not all of the Stand for Children candidates won, the organization's ability to make large six-figure contributions to Illinois politicians bought access to Illinois political leaders, including House Speaker Michael Madigan. Because of the Stand for Children influence, Madigan sidestepped the Illinois General Assembly's education committee and created a new "School Reform Committee" of the Illinois House of Representatives, and installed Republican Roger Eddy and Democrat Linda Chapa La Via as co-chairs of the committee. Both Eddy and Chapa La Via were fiercely prejudiced against the Chicago Teachers Union and uncritically accepted the lurid testimony of Stand for Children and Advance Illinois during the two days of hearings on "reform" staged in Aurora on December 16 and 17 2010.ROSS WEINER. Welcome, IŌĆÖm Ross Weiner, Executive Director of the Aspen InstituteŌĆÖs Education and Society program, and IŌĆÖm just going to, uh, introduce this session very briefly, and turn it over to Jim and Jonah.

Um, so, before I do, I just wanted to say, you know, following education policy over these last couple of years has really been quite a roller coaster. ThereŌĆÖs... a tremendous amount has gone on, and I think, you know, weŌĆÖll find out over the coming years, what of it was productive and what of it we should have fought more about even at the time. But I think weŌĆÖve got a really unique opportunity to learn from whatŌĆÖs just gone on in Illinois over these last, you know, few months and year, um, because it really is quite a different model than what weŌĆÖve seen.

You know, we saw so many headlines about Wisconsin, and the sit-ins, and the protests, and just the really heated polarizing nature of so many of the education policy debates that have gone on in the last couple of years. And Illinois really took a different tack, an all hands on deck, everybodyŌĆÖs in the room, weŌĆÖve got to figure this out, because we need to do better, for our kids.

And so I think thereŌĆÖs really a lot to learn from and, you know, hopefully I think thereŌĆÖs an open question, but I think thereŌĆÖs something hopeful about the kind of collaboration weŌĆÖve seen in Illinois about the possibilities, now that itŌĆÖs time for implementation.

Chicago multi-millionaire Kenneth Brody (above right, in a photo from a New York charity event) contributed $100,000 to the Stand for Children Political Action Committee (PSC) on December 23, 2010, according to Illinois State records. Brody is Manager of the DRW Trading Group in Chicago.So IŌĆÖm really excited to learn from these two folks who were prime actors in this drama. So weŌĆÖll turn it over in a minute to Jim Crown, who is a trustee of the Aspen Institute, and sort of you know very involved in education and civic matters in Chicago, and Jonah Edelman, the co-founder and CEO of Stand for Children, an advocacy organization around improving public education thatŌĆÖs sort of in, nine states across the country, is that right?

Chicago multi-millionaire Kenneth Brody (above right, in a photo from a New York charity event) contributed $100,000 to the Stand for Children Political Action Committee (PSC) on December 23, 2010, according to Illinois State records. Brody is Manager of the DRW Trading Group in Chicago.So IŌĆÖm really excited to learn from these two folks who were prime actors in this drama. So weŌĆÖll turn it over in a minute to Jim Crown, who is a trustee of the Aspen Institute, and sort of you know very involved in education and civic matters in Chicago, and Jonah Edelman, the co-founder and CEO of Stand for Children, an advocacy organization around improving public education thatŌĆÖs sort of in, nine states across the country, is that right?

So weŌĆÖre thrilled that youŌĆÖre here, and thanks for coming to the [Aspen] Ideas Festival, and weŌĆÖll turn it over to you...?

(Time 1:55)

JAMES SCHINE CROWN. So thank you, thanks for that introduction, and thanks everybody for for being here. And uh we put this forward this education-centric session, uh, this is really going to be an hour about politics and political action, and so there might have been a little camouflage in the titling, because while the nobility of the outcome we hope is something that we can all be proud of what youŌĆÖre really about to hear what happened in Illinois is a story of fairly straightforward, very rudimentary political activism, and it could apply to things other than education, in this case it applied importantly to the educational system in Illinois and in Chicago.

And it really was thanks to Jonah and one other person that Illinois went from having one of the worst statutory environments for education reform to what is, we hope, a model for virtually all the other states. And while this subject might sound like a very local to some, you know, educational reform in Illinois, I think this Senate Bill 7 that just signed by the governor a little while ago might well be regarded as most important new model for legislative reform and educational reform in any of the fifty states.

I want to set the context, before handing it over to Jonah, to describe what we were up against, and what the environment was, and he way I to set the context is to blend three streams of recent history, because all these things are complicated.

LetŌĆÖs talk about what the educational system looked like in Chicago. Six hundred and seventy-five schools, 122 of them were, are high schools. We have 71 charters. The school system is the second largest employer in the city, with over 40,000 employees, about 25,000 of them are teachers, all unionized. The budget is fairly substantial, itŌĆÖs the third largest school system in the country, it has a $5.3 billion budget and right now weŌĆÖre running a projected $700 million deficit. So those are kind of just the bare facts.

How does that school system performing?

In a word, ŌĆ£awful.ŌĆØ And people remember it as being a poster child many years back for the failure of inner city public schools.

We have the shortest school day of any major public school system. And when Rahm Emanuel was running, he liked telling, anecdotally, the story of a kindergartner in Houston public schools and a kindergartner in Chicago public schools, by they time they receive their diploma, if they do, as seniors the Houston public school student will have received four years more than the Chicago public school student.

Imagine missing four years of face time with teachers because of the length of the school year and the length of the school day.

The dire statistics go on. Less than half of the high school, people who show up for high school, graduate in five years. And only eight percent, eight percent, of students who start as freshmen in a Chicago public high school will graduate a 4-year college the time theyŌĆÖre 25. And if youŌĆÖre an African American male that number is three percent. So think of the human capital loss when 97 percent of the African American males that start in the Chicago public school system have no statistical shot at coming out of a 4-year college with a degree.

Um, teacher quality, another very interesting statistic. Those of you who are close to academic institutions know that at state schools, education officers talk about an ACT score of 20, is a kind of a floor for being able to succeed at a decent four-year college. The average ACT score of Chicago public high school teachers is 19, and that includes the upped average we now have because we have a strong Teach For America corps in those numbers. It was lower than that before TFA was folded in. So thatŌĆÖs the school system.

What was the political context? Illinois, as I think everybodyŌĆÖs observed in the last couple years, is a pretty blue state, and a history of either liberal Democratic governors or occasionally governors who use the state house as a weigh station to federal prison.

Either way it has not had strong executive leadership. And it has had a dominant voice from the well mobilized and well organized political action groups, including unions, and especially the teachersŌĆÖ unions which are quite strong throughout the state of Illinois and in Chicago.

We do have a very strong speaker, Speaker Madigan. Mike Madigan is probably the most powerful political person in the state, frankly, in terms of being able to make things happen, but heŌĆÖs a political pragmatist. And the unions historically have been very well mobilized politically to pursue their agenda. And they were always there in every campaign cycle, over four and a half million dollars ($) in contributions going back to 2,000, and they knew what they were doing and did it well over the time period.

So basically they had the best shot at writing the rules.

So what did that give us? There actually is one more state in the union that is more strike permissive than Illinois was. Anybody want to guess what it was? Vermont.

All the public school students in Vermont would fit in two high schools in Chicago. But Vermont is the only state in the union that had a more permissive strike regime than Illinois did. Now there were a couple who were almost as permissive, Hawaii, Minnesota and Montana.

But people talk about right to strike, we reference Wisconsin, and what happened there. It is a well accepted political concept, I think, in this country, teachers, no not teachers, firefighters policemen, flight attendants, some people have to mediate, canŌĆÖt strike. And in fact in forty-five of the fifty states there is no right to strike by teachers. Thirty-nine have absolutely no right to strike and six others require fact finding first. So this was an incredibly strike permissive environment with these other efforts by the unions, and so forth, that created an unsustainable structure in our school system.

People might also, especially in this environment, be aware, you know, we had a mayor who talked importantly about reforming the schools, Mayor Daley, and we had a CEO of public schools, Arne Duncan, who did everything he could in that environment.

But this was not a fair fight.

Because of the political strength and the organized strength of the unions, who, each time they came up to a contract session, would not concede on length of day, would not concede on teacher metrics and would insist on additional compensation. And thatŌĆÖs the way things have gone for an entire generation in terms of negotiated outcome.

One last bit of context before I ask Jonah to describe what we did with that circumstance. Chicago has a very engaged private citizen community that wants to make the city better. Those of us that live in Chicago are extraordinarily proud of how engaged and committed people are to civic leadership across all domains. This includes education.

And education received a lot of funding, a lot of attention, and it was from virtually every corner that you could imagine. It was corporations, it was civic organizations, it was the private sector, it was foundations. But I feel like a lot of what we did there was, I donŌĆÖt want to make it sound marginal by saying it was at the margin, but it was something outside the core structure. It was not structural change. It was the charter schools, it was bringing in Teach for America, it was bringing specific programs of human enrichment as an overlay on what was basically there.

And I have to say working at the edge like that, for some people, was getting to be frustrating and frankly quite discouraging. I have a couple friends, they speak with a bit of hyperbole, but they will say things like you know, ŌĆ£I have put thousands of hours and millions of dollars into this. We have accomplished nothing, IŌĆÖm done here.ŌĆØ

And, were we really at an inflection point when Rahm Emanuel was elected? I donŌĆÖt know. Were we really at an inflection point when this bill came up? I donŌĆÖt know. But people were talking about it like, ŌĆśOK, we will give it one more shot with our philanthropic dollars and with our time, and if we canŌĆÖt get it right this time, IŌĆÖm going to put my efforts and money into something where I can actually live to see the benefit,ŌĆÖ because people were quite frustrated with the benefit they werenŌĆÖt seeing up until then.

So into that maelstrom walks Jonah Edelman. And you heard a little bit about Jonah, Stand for Children was organized, in, well I guess DC was the first place you worked, but itŌĆÖs based out of Oregon. And Jonah, through some mutual friends, approached several of us who had been working on this, to talk about how he thought maybe he could help make things different, and he was quite persuasive that he could. And so weŌĆÖll move to having him explain exactly what that was.

I guess I just will give you a little bit of a commerical, because if you look at the website, it does have a rather moving phrase about where the name comes from. And it was a quote from Rosa Parks, who was part of your Washington, DC event, who said, ŌĆ£If I can sit for justice you can stand for children.ŌĆØ And that is the credo of the organization.

And Jonah, why donŌĆÖt you talk a little bit about what you did.

(12:14)

JONAH EDELMAN Thank you all very much for coming.

There are a few positives I want to point out. Jim hit the political context squarely on the head. A few things that were also important to note.

An organization called Advance Illinois, which some of you may know about, was founded a few years before Stand came to Illinois, by the Joyce Foundation and the Gates Foundation. And itŌĆÖs a terrific organization led by a wonderful leader, Robin Steans, and itŌĆÖs very strong on political advocacy, had Bill Daley as co-chair before he went to the White House, and Jim Edgar, former governor.

So thatŌĆÖs a great asset in that state. And they had led a process, which was collaborative, to establish a better way to evaluate teachers. The catalyst for that was the federal Race to the Top money that you might be aware of. Are you aware of the Race to the Top competition where Arne Duncan put together $4 billion, let states bid, a great catalyst for change, and Illinois went as far as its politics would allow it, by coming up with a new way of evaluating teachers ŌĆö no consequences ŌĆö but a good first step.

And I think it is really important to mention.

So coming to town I was aware of that, and I was also aware of the entrenchment, and frankly when Bruce Rauner (Chicago venture capitalist and Republican), who is mutual friend of JimŌĆÖs and probably many of you in this room, whoŌĆÖs been involved in education for many years, asked, after seeing that we passed legislation in several states including Colorado, that we look at Illinois I was skeptical.

And after interviewing 55 different folks in the landscape, Speaker of the House, Senate President, minority leadership, education advocates, I met with Jim and many others was very surprised to see that there was a tremendous political opening that I think Bruce wasnŌĆÖt aware of.

And that was that the Illinois Federation of Teachers still inexplicably went to war with Speaker Madigan who Jim cited as a very, very powerful figure, had been speaker for 27 years, with the exception of couple years between ŌĆÖ94 and ŌĆÖ96, over an incremental pension reform. And Jim many others are die-hard advocates for pension reform in Illinois. And the pension reform that happened in 2010 is not the reform thatŌĆÖs needed in Illinois, but it was a first step, only affecting future employees.

The union could well have, probably, definitely should have, thanked Madigan for not going further. Instead they decided that the $2 million theyŌĆÖd been giving him reliably for election campaigns, that they would take that away, that they would refuse to endorse any Democrat who voted for that legislation, even those that had been loyal supporters for years, and they went to the AFL-CIO to try to get them to do the same.

So a major breech, and itŌĆÖs something just as you kind of starting to think of ways in which the context of Illinois is similar to other states that context, weŌĆÖre starting see that in other states Democrats who are still in control are having to address these terrible fiscal issues and in so doing thereŌĆÖs often conflicts that are arising.

So thereŌĆÖs this breech, and Stand, with the support of Jim, Brian Simmons (Code Hennessy & Simmons, Hedge Fund), and a few others, Ken Griffin (CEO of Citadel LLC, Hedge Fund). Well, actually, initially Jim, Matt Hulsizer (CEO Peak6 Hedge Fund), Paul Finnegan (CEO of Madison Dearborn Partners). We decided to get involved with mid-term elections, which many advised us against doing because we were new to town, we donŌĆÖt know the landscape. But my position was we had to be involved to show our capability to build some clout. So we very quickly researched the situation and while there were a lot of folks who thought that Republicans were going to take over in Illinois our analysis was that Madigan would still be speaker, and that was you know district by district, just passionate. That wasnŌĆÖt what I think a lot of our colleagues wanted to hear.

JAME SCHINE CROWN

One of the several spikes of Blagojevich indictment headlines ŌĆō no seriously - as a political flow you would have bet against people running in his shadow.

JONAH EDELMAN

ThatŌĆÖs exactly right. And thereŌĆÖs obviously a red wave last cycle.

And so our analysis was he was still going to be in power, and as such the raw politics of it were that we should tilt toward him. And so we interviewed 36 candidates in targeted races and essentially, IŌĆÖm being quite blunt here, the individual candidates were essentially a vehicle to execute a political objective, which was to tilt toward Madigan.

So the press never picked up on it. We endorsed nine individuals, and six of them were Democrats, three Republicans, and tilted our money to Madigan, who was expecting that because of Bruce RaunerŌĆÖs leadership, and Bruce is a Republican, that all of our money was going to go to Republicans. That was really as show of, an indication to him, that we could be a new partner to take the place of Illinois Federation of Teachers - that was the point.

Luckily, it never got covered that way. That wouldnŌĆÖt have worked well in Illinois. Madigan is not particularly well-liked. And it did work.

After the election, Advance Illinois and Stand had drafted a very bold proposal we called Performance Counts. It tied tenure and layoffs to performance. It let principals hire who they choose. It streamlined dismissal of ineffective tenured teachers substantially, from 2+ years and $200, 000 in legal fees, on average, to three to four months, with very little likelihood of legal recourse, and, most importantly, we called for the reform of collective bargaining throughout the state. Essentially, proposing that school boards would be able to decide any disputed issue at impasse. So a very, very bold proposal for Illinois, and one that six months earlier would have been unthinkable, undiscussable.

And after the election, I went back to Madigan and I confirmed, I reviewed the proposal, and I confirmed his support, and he was supportive. The next day he created an education reform committee and his political director called to ask for our suggestions for who should be on it. And so in Aurora, Illinois, in December, out of nowhere there were hearings on our proposal.

In addition we hired eleven lobbyists, including the four best insiders and seven the best minority lobbyists, preventing the unions from hiring them. We enlisted a statewide public affairs firm. We had tens of thousands of supporters. And with JimŌĆÖs, and many others stepping up, Paula and Steve, thank you, we raised $3 million for our political action committee between the election and the end of the year. ThatŌĆÖs more money than either of the unions have in their political action committees.

And so essentially what we did in a very short period of time was shift the balance of power. I can tell you there was a palpable sense of concern if not shock on the part of the teachersŌĆÖ unions in Illinois that Speaker Madigan had changed allegiance, and that we had clear political capability to potentially jam this proposal down their throats, the same way the pension reform had been jammed down their throats six months earlier. In fact, the pension reform was called Senate Bill 1946 and the unions took to talking to each other about it like, ŌĆØweŌĆÖre not going to allow ourselves be 1946ed again,ŌĆØ using it as a verb.

And so in the short, so the short lame duck session in January, called lame duck session, because some lame ducks are allowed to take a last vote for politically difficult topics, proposals. We made an attempt to do just that. And we werenŌĆÖt able to move our proposal. And in my analysis to Jim and others was that it went a little too far for Illinois. But as youŌĆÖll see in just a second it was an effective starting point, because we started extreme we gave ourselves room to come back.

Senator Kimberly Lightfoot, who has been a reliable supporter of unions, and in the middle of education policymaking, intervened. She has a lot of clout in the Senate. She helped elect the Senate President, John Cullerton, and she forced groups to the table.

The unions were thrilled to come to the table and discuss things that again nine months earlier they would not have been willing to discuss. And so, in the course of three months, with Advance Illinois taking the negotiating lead, my colleague, Jessica Handy, our policy director in the room for every meeting. And - with Advance and Stand working in lockstep, and that unity is so important, that partnership, caucusing before every meeting and caucusing after every meeting, making plans - they essentially gave away every single provision related to teacher effectiveness that we had proposed. Everything we had fought for in Colorado down to the last half hour in the legislative session, they gave us at the negotiating table.

Not irrationally, not idealistically. It wasnŌĆÖt a change of heart. ItŌĆÖs because they feared that we were able to potentially execute our collective bargaining proposal, (enact it?).

Unions are more, very logical. TheyŌĆÖre concerned mostly about their dues and their membership, and then next up, collective bargaining, and pensions are somewhere around there. And then teacher effectiveness reform, you know, issues, tenure, layoffs compensation ŌĆō thatŌĆÖs tertiary for them. So if you show the capability to actually enact collective bargaining reforms theyŌĆÖre logically going to give on everything short of that to pull back the barricades. And so this was the strategy led by the IEA.

And I should note that the Illinois Education Association, which is the down-state union, which is the better resourced union with more members, has a history of pragmatism, and they led on this negotiation; they really kind of brought the other the unions along.

Joe Anderson, the former head of the Illinois Education Association now works with Arne Duncan in the Department of Education and his son, Josh, is the head of Teach For America in Chicago. And the new director, Audrey Soglin, is very pragmatic.

I doubt this tape will ever get to her, but I would say that IŌĆÖm interested in talking at some point, about, at end of the day, if she was happy to get these issues resolved. I donŌĆÖt think she liked defending seniority-based system.

So in that intervening time Rahm Emanuel is elected mayor on the first ballot, and he strongly supports our proposal. Jim talked about the talking point that he probably talked about a thousand times about Houston kids going to school for four more years than Chicago kids. That was another shoe that dropped. And it really put a lot of pressure on the unions, particularly the Chicago Teacher Union because they didnŌĆÖt support him.

So hereŌĆÖs what ends up happening at the end of the day. April 12th, weŌĆÖre down to the last topic of collective bargaining. ItŌĆÖs been saved for last. ItŌĆÖs the hardest topic. We fully expected that we would, our collaborative problem-solving of three months would end, and we would have an impasse and go to war. And we were prepared. We had money raised for radio ads and our lobbyists were ready.

Well, to our surprise, and with Rahm EmanuelŌĆÖs involvement behind the scenes, we were able to split the IEA from the Chicago TeacherŌĆÖs Union.

And in January, just after we hadnŌĆÖt gotten our proposal through in the lame duck session, IŌĆÖd worked with a labor lawyer named Jim Franczek who is absolutely brilliant, if any of you know him, and his partner of counsel Stephanie Donovan on fallbacks. And Jim and the other supporters had approved fallbacks from our initial proposal, essentially isolating Chicago and calling for binding arbitration or a fact finding process that wasnŌĆÖt binding, but would have a high threshold for unions to approve.

We came with a fallback for binding arbitration when we saw that the Illinois Education Association was willing to do a deal, and just focus on Chicago. They interestingly pressured the Chicago Teachers Union to take the deal. Karen Lewis, the head of the Chicago Teachers Union, whoŌĆÖs a die-hard militant, was focused on maintaining her sense of her membersŌĆÖ right to strike. Her sense was that binding arbitration was giving away the right to strike. But our next proposal, our next best, which was a very high threshold for strikes, for whatever reason, tactical miscalculation on her part, was palatable.

Rahm pushed it, Kimberley Lightfoot pushed it.

WeŌĆÖd done our homework. We knew that the highest threshold of any bargaining unit that had voted one way or the other on a collective bargaining agreement, contract vote was 48.3%. The threshold we were arguing for three quarters. So in effect they wouldnŌĆÖt have the ability to strike even thought the right was maintained.

So in the end game the Chicago Teachers Union took that deal misunderstanding probably not knowing the statistics about the voting history, and the length of day and year was no longer bargainable in Chicago. And we insisted that we decide all the fine print about the process. She was happy to let us do that.

With the unions then on board, they were relieved, the IEA and IFT, were relieved to have a deal, they came out strongly in support of this agreement which was this wholesale transformational change. And with that support there was no reason for any politician to oppose it, so the Senate backed it 59 to zero.

And then the Chicago Teachers Union leader started getting pushback from her membership for a deal that really probably wasnŌĆÖt, from their perspective strategic. She backed off for a little while, but sheŌĆÖd already, the die had been cast, sheŌĆÖd publicly been supportive. So we did some face-saving technical fixes in a separate bill, but the House approved 112 to one. And a liberal Democratic governor who was elected by public sector unions, thatŌĆÖs not even debatable, in fact signed it and took credit for it.

So we talk about a process that ends up achieving transformational change thatŌĆÖs going to allow the next, the new mayor and CEO to lengthen the day and the year as much as they want.

The unions cannot strike in Chicago. They will never be able to be able to muster 75% threshold necessary to strike. And the whole framework for discussing impact, you know, what compensation is necessary is set up through the fine print that we approved, to ensure that the fact finding recommendations, which are non-binding, will favor what we consider to be common sense. So thatŌĆÖs what happened.

And IŌĆÖm, weŌĆÖre really happy to open this, but weŌĆÖre talking about opportunity now for transformational change across Illinois in that principals will have the power to dismiss ineffective teachers, that theyŌĆÖll able to hire who they want, that theyŌĆÖll no longer be forced to accept teachers they donŌĆÖt want in their buildings, and that when layoffs happen they will be able to let people go on performance not just seniority. And, in Chicago, theyŌĆÖll be able to lengthen their day and year which has just been a horrible inequity for decades.

And all this with the narrative of union leadership. Because it was a fete accompli and the unions decided smartly that they would pursue a win-win. We gave them the space to win. WeŌĆÖve been happy to dole out plenty of credit. And now it makes it hard for folks leading unions in other states to say this is, these types of reforms, are terrible, because their colleagues in Illinois just said these are great.

So our hope and our expectation is to use this as a catalyst to very quickly make change, similar changes, in very entrenched states. And thatŌĆÖs the overview of what happened.

28:18

JAME SCHINE CROWN - Summary Points

Jonah, thanks.

So IŌĆÖm going to make four summary points and then we will throw it open to questions and dialogue and be very interested to hear how people are reacting to this based on where youŌĆÖre coming from.

The observations I would make are that:

(1) obviously special interest politics are alive and well in America, and the point isnŌĆÖt whether they are good or bad, itŌĆÖs whether or not they are well organized and funded, and have a noble goal, but this is special interest politics.

(2) What was unusual, I think, is that there was actually never a special interest advocacy group that was focused on pro children education reform. There was not a special interest for that cause, and that one did develop was instrumental.

(3) Also, obviously, this had to be a financial and political priority. We all have our political priorities when we go in the ballot box, it can be taxes, choice, regulation, the role of government. This seems to be important to everybody, but not a decision point for what candidtates they really back. And until that happened, this election cycle, this way, it was going to be like complaining about airline food. Everybody may do it, but unless you change your choice of airlines because of it, theyŌĆÖre not going to change their food, itŌĆÖs going to be price and schedule. Which, data shows people react to what the customer actually is asking for.

(4) Then the last thing IŌĆÖll mention, and this was a bit of the epiphany that occurred, at least for me and some others that were very much a part of this effort. Jonah has mentioned several, but not all. We were very proud of what we were doing as a family in Chicago, as a philanthropy, as citizens, but we had to take our fight where the fight was. We had never gone to Springfield with these issues. You know, principals, schools, mayors, yes. But we had never gone where the fight was. And I think until you take this to where the fight is youŌĆÖre going to end up with the cycle that endured for a generation and the frustration we did. And so weŌĆÖre very pleased that we finally cracked the code on that one.

So with that weŌĆÖll love to hear your questions and comments. Yes, right here... 30:35 Q&A QUESTION 1

Can you tell a little bit about how youŌĆÖll define success and how you will measure that?

JONAH EDELMAN

For us, itŌĆÖs college-ready high school graduation, and then you know, leading to that, itŌĆÖs children who are on track. Now weŌĆÖre going to get into broader topics of problems in American public education, here, itŌĆÖs opaque. You know, thereŌĆÖs just not enough clarity about whoŌĆÖs on track and whoŌĆÖs not. Every state defines their own graduation standards and they have their own assessments. You know I think one of the things we could do collectively, that would make the most difference, is in whatever way you can, ensure that the common core common standards, common standards across the country for high school graduation, are implemented, and that assessments are executed, and they go into effect, and thereŌĆÖs a common definition of a kid whoŌĆÖs on track and whoŌĆÖs not and more transparency. ThatŌĆÖs the bottom line, but the statistics that Jim cited have to change or weŌĆÖve done accomplishes, has accomplished nothing.

QUESTION 2

WeŌĆÖre still facing a $700 million budget default. Is the group holding together to attack this issue across the state our has the group you moved to other issues in the city and state?

JAME SCHINE CROWN

OK, IŌĆÖm not sure who is the ŌĆ£youŌĆØ is in that sentence.

Question 2 person

The political group.

JONAH EDELMAN Stand for Children.

JAME SCHINE CROWN

Stand for Children and Advance Illinois.

JONAH EDELMAN

Absolutely. WeŌĆÖre building an affiliate for the long term and we have a great staff already. There has to be a statewide constituency of parents and educators. And there has to be a very, very proactive strategy in Chicago and outside Chicago. Our first focus is in Chicago is ensuring the district is able to follow through on instructional time increase. Now while the rules allow the mayor to increase instructional time it canŌĆÖt become something thatŌĆÖs a terrible issue for him politically. So we have to organize and mobilize the support to make it a winner politically. So weŌĆÖll be there to support the mayor. We also want to get parents engaged in the topic. Because top down change only without educated only goes so far. So weŌĆÖre hoping to have tens of thousands in a discussion around how time will be used in Chicago so when the mayor comes forward, be it September or next spring, to enact a longer day and year, that there is a community groundswell of support.

QUESTION 3

But youŌĆÖll still have a $700 million bogey, and given the Washington, DC example, it can get very, very difficult in a Chicago type community to ram through cutting teachers and all the other kinds of stuff youŌĆÖre going to need to get to the vote.

JAME SCHINE CROWN

YouŌĆÖre right to predict some more turbulence on this topic. ItŌĆÖs hard for us to see, just as citizens of Chicago how theyŌĆÖre going to solve this. WeŌĆÖve got a new school board, and a new CEO of public schools They are working this, theyŌĆÖre disaggregating, and they have $15 million here and $22 million there. And it seems to me that will be operating in the red for a while. IŌĆÖm not sure how that works as a matter of cash management. But they have got a serious uphill problem, and the ŌĆ£theyŌĆØ in this case is the school board, and the political administration, and how the mayorŌĆÖs going to deal with that is a front and center problem. He will go down, he wonŌĆÖt get it to zero and that may create some, you may be hearing about this topic again because of that. Trying to lengthen the day while paying people no more is obviously going to stress things.

QUESTION 4

Has the private sector become really even more important now than they were in the start?

JAME SCHINE CROWN

My forecast is that in the immediate term this is now back in the mayorŌĆÖs court and the school boardŌĆÖs court about getting things in place with principals and metrics and quality schools and so forth at the CPS level. Right after that, the private sector has got a great partnership opportunity to come in and do things that will be effective and strategic, once this is sorted out. But the ballŌĆÖs on the other side of the net for the mayor to get stuff done before we can come back in as private citizens and truly be helpful, I think.

QUESTION 5

Do you have any curricular reforms planned on the new common core standards?

JAME SCHINE CROWN

The question is whether or not there has been Curricular reforms and thatŌĆÖs really not been something that...

JONAH EDELMAN

WeŌĆÖve encouraged state boards of ed in some states to adopt the common core standards. But the lead group on that is Achieve, and the Chief State School Officers, and the NGA, and theyŌĆÖve done some great work on it, so Stand isnŌĆÖt involved at that level.

QUESTION 6

Tennessee recently enacted a collaborative conferencing model to do negotiations, and I was wondering how you felt about that?

JONAH EDELMAN

I was just in Tennessee a couple weeks ago, and I think thereŌĆÖs big questions around how itŌĆÖll play out. Obviously, you want a balanced negotiation process, where a threat of a strike canŌĆÖt take issues off the table, and where, you know, management needs to have some discussion so thereŌĆÖs some ownership and buy-in on the part of the workforce. And, you know, IŌĆÖm eager to see how that works IŌĆÖm also, I also think thereŌĆÖs some possibility of enacting similar improvements in urban districts in Tennessee as a result of that contract change.

QUESTION 7

IŌĆÖm wondering about how optimistic you are about scaling this to states that have very, very, entrenched union. IŌĆÖm from New York, and I was listening to your whole battle plan, and wondering if you think that either your organization or others can go to a place like Albany and get private philanthropy to partner with you to see the kinds of reforms that happened in Illinois in other states like New York?

JONAH EDELMAN

Yes, for sure. I think itŌĆÖs a question of resources, skill and then unity. I think those are the key ingredients. New York already has a good group called Education Reform Now, and I think thereŌĆÖs another group that I canŌĆÖt mention that may come in with even more forcefulness in New York. ItŌĆÖs really a question of niche and need. If weŌĆÖre invited there if thereŌĆÖs a group that really wants us to come and thereŌĆÖs a niche, weŌĆÖre open to it. Illinois has very entrenched politics. ThereŌĆÖs really no... There might be a degree of difference with California, which probably is the worst, and then New York, but itŌĆÖs really the same...

JAME SCHINE CROWN

You donŌĆÖt want to be in these playoffs, even if youŌĆÖre not going to win.

JONAH EDELMAN

Yeah. And so, Massachusetts, we have nine affiliates, and weŌĆÖre growing to 20 states by the end of 2015. The calculus is always the same for us: itŌĆÖs about whether thereŌĆÖs a near-term education reform opportunity, niche, champions, ability to scale. and sustain. WeŌĆÖre not here to pass a law and leave. The questions have already been asked. This is about long term change. And itŌĆÖs from capitol to classroom.

So New York is certainly a state we could work in, if there were a need. The key in New York is youŌĆÖre not going to change the speaker of the assembly. The question is whether or not you can get 2/3ŌĆÖs support. And so just as you saw an incredible transformation on gay marriage in New York that just happened. You know, itŌĆÖs basically the same legislature, different result because of better political strategy and execution. The same can happen on education in New York.

QUESTION 8

WhatŌĆÖs the future with pension reform? Is that going to be next, because thatŌĆÖs really the biggest problem.

JAME SCHINE CROWN

For those that like feeling better about their state finances, Illinois has a $113 billion unfunded deficit due to these unfunded entitlements. We are held up against, per taxpayer, the worst, held up against the ability to generate revenue, the worst, or one of the worst, and we tried we being the state, to go after this, in a sort of, I would say, moderate intense way before the legislature adjourned.

The votes were not there, and they said weŌĆÖll try to do it over the summer session. So it was deferred for lack of political capital to get it done. Whether or not itŌĆÖs deferred further I donŌĆÖt know.

WhatŌĆÖs happened more recently, is that the tax increase that occurred in January, we raised personal and corporate income taxes significantly, has resulted in at least an announced, I donŌĆÖt know if itŌĆÖs threats or actual I donŌĆÖt know, but itŌĆÖs an announced flight of corporate headquarters that has had Governor Quinn every day hosting a new corporation cutting a special tax deal for them. And so weŌĆÖve still got a lot to sort out on the balanced budget in Illinois, and the political will is not yet organized enough to get something done.

QUESTION 9

IŌĆÖm from DC, and we saw this happen with Fenty putting a lot of what you guys are about. He lost the election because he was unable to distinguish what that employment meant for teachers and what kidsŌĆÖ rights were. And essentially the electorate saw that employment opportunities were being taken by this mayor. What public relations strategy did you use in Illinois to distinguish the fact that kids needed to have a better chance for their future as opposed to folks who have no business being on the payroll stay on the payroll?

JONAH EDELMAN

First of all, I donŌĆÖt agree that being why Fenty lost. I would disagree with that premise.

Question 9 person. Yeah, but it was a substantial reason though within the city. Fenty could still be mayor of DC easily. Politics is an art form. And I think when you read accounts of reformers or elected officials who try to rule by fiat, you know, and do things without practicing the art of politics, which is labor-intensive, relationship-based. You know, IŌĆÖm from DC, and I know a lot of people there. And I think, you know, youŌĆÖve got to go to funerals. YouŌĆÖve got to meet with people. YouŌĆÖve got to meet with people who backed you. You gotta put people in key positions who are going to treat people respectfully. And, you know, you donŌĆÖt do that you pay a price, politically. And he could have done all the educational changes, even in the way that they were done, which really could have been more diplomatic, and still won, had he, you know, done his business politically.

That being said, you know, our issues poll really well, actually. And thatŌĆÖs our theory of action, is to focus on issues that the public strongly agrees with, but special interest politics have prevented from happening. And use, as Jim said, special interest politics on our side.

Our theory of action doesnŌĆÖt work on issues that donŌĆÖt poll well. And so, you know, and again, we donŌĆÖt come with a one size fits all to a state. And we donŌĆÖt come in with our fingerpointed, you know, ready to poke people in the eye. We try to build as much political clout in the most unassuming, diplomatic way. Go for bold change, and do it in the most bridge-building possible way. If you see a leader like Audrey Soglin, give her the ability to lead. Give her the space to win. And donŌĆÖt, you know, play win-lose politics.

Unfortunately, Washington, Oregon and California, you got to play win-lose politics because of the way the unions operate. So you canŌĆÖt be shy about that. But itŌĆÖs just operating in a fairly disciplined strategic way at all times, and not saying things just because you want to say them. They feel good to say. But they actually arenŌĆÖt strategic when youŌĆÖre trying to achieve a political result.

QUESTION 10

Do you see any future for your organization working within Vincent GrayŌĆÖs administration on any type of education reform?

JONAH EDELMAN

WeŌĆÖre not working in DC. ThereŌĆÖs a good group called DC School Reform Now, that was founded by one of our board memberŌĆÖs, Kristin Ehrgood, that I think very highly of, and we provide some technical assistance. And DC has some great opportunities. I think Kaya HendersonŌĆÖs a terrific leader. I think Mayor Grey is very open. They have an incredible opportunity with their charter sector in DC. I mean itŌĆÖs got some real scale. If they could get their quality issues under control, and close some of the bad charters, you could see a lot better results. It could potentially be a model.

QUESTION 11

(See foundation) What you all did in Illinois is just brilliant, but IŌĆÖm trying to think about the scalability, and (a) Drill down a bit, more on that, because youŌĆÖre not going to find a seam between between you know an unbelievably powerful speaker and even though it would be great, but the big thing you said and you said it so matter of factly, you raised $3 million in contributions that exceeded what the teachers unions. One, can you talk more about that?

JONAH EDELMAN

Jim should talk more about it.

(b) And what are states, could you name some, where you think the lessons of Illinois could be replicated? (c) I heard what you said about the teachersŌĆÖ unions you know having to sign on but they got weak, weak-kneed. Are they sticking to their support after the fact.

JONAH EDELMAN

(c) Absolutely. So the last question first, The IEA and IFT are thrilled. TheyŌĆÖre writing OpEds in national publications about Illinois, you know, being an education reform leader, not mentioning Stand for Children. ThatŌĆÖs fine. And thatŌĆÖs great. ItŌĆÖs a great narrative. The bill-signing. I was saying to Jim, it was a great example of politics in action. You know, Stand for Children was hardly mentioned. Many of the fathers of that success who were absent for the conception, and you know the gestation, and birth of the child were claiming credit for paternity. It was terrific and thatŌĆÖs how it works. So I think this is an enduring change and the implementation is going to be quite smooth. And the CTU president probably is going to have some trouble based on putting herself in a position where sheŌĆÖs got a terrible reputation now in Springfield and now she has some trouble internally, so sheŌĆÖs got some challenges.

JAME SCHINE CROWN

I guess the comment IŌĆÖd make about the $3 million, this was just straightforward pragmatism. I mean holding aside value judgments, or social objectives, or any policy conversation, what are the facts? YouŌĆÖve got well organized teachersŌĆÖ unions who have political campaign chests, they have workers to show up to meetings who are mobilized to do what is in their interests. And that is an absolutely standard conventional appropriate factor in American politics.

There was no counter weight. There was no organized force to have a rational legislator say, ŌĆ£well you know these guys are helping me in my district and you guys are giving me lectures about 3 percent canŌĆÖt go on to college, you know and I realize that, but my issue is getting elected because IŌĆÖm not going to solve all these problems between now and November.ŌĆØ

So the pragmatic response is, ŌĆ£We get it. You would like to stay in office and you would like to stay in office backed by people you can then pursue that agenda as long as youŌĆÖre finding alignment.ŌĆØ

So forget the rhetoric, forget the speechmaking that we would all do, and say, ŌĆ£OK, we will have money and it will go to you if you are backing this as a political priority and it will go to the opposite of you if youŌĆÖre not.ŌĆØ

JONAH EDELMAN

What was your calculation? I mean for you it was a departure.

JAME SCHINE CROWN

ThereŌĆÖs a high squirm factor in doing this. First of all, youŌĆÖd like to think that the merits of arguments are compelling. And candidly this is fraction of what weŌĆÖve all spent on charter schools and, you know, scholarships and all these other things, and it added up to $300 million, and it was hundreds of thousands for many of us. And it was all of a sudden check writing that we said, ŌĆ£OK , we get it, the outcome here wonŌĆÖt be new computers, it will be this person will in office not that person.ŌĆØ And you just had to choose that this was the path you wanted to be on.

JONAH EDELMAN

(b) And we can do that in other states. Yeah, weŌĆÖre already getting going. I mean the thing about the way we work is weŌĆÖre doing this level of work in every state that weŌĆÖre in. And so itŌĆÖs not one person, itŌĆÖs significant organizations, led by stellar executive directors who operate as CEOs.

So in Washington state right now, weŌĆÖve got exactly the same goal, and itŌĆÖs another state that doesnŌĆÖt lack for financial resources, itŌĆÖs about achieving the same kind of reallocation. We could readily outspend the Washington Education Association.

Massachusetts, very similar. It might be a ballot measure in Washingon, it might be we have a measure on the ballot, and we use it as a lever in Massachusetts. ItŌĆÖll look a little bit different, but itŌĆÖs essentially the same.

Iowa is another state, you know, Democratic senate, feel like we could do the same. Very, very major reform potential there.

So I donŌĆÖt think thereŌĆÖs any question but by the end of this decade weŌĆÖre going to have ended seniority-based decisionmaking in education in this country. ThatŌĆÖs not enough to ensure better outcomes but ItŌĆÖs certainly something that has been long overdue.

QUESTION 12

Just wondering as a component tied in with all the other reforms, what do you expect the timeline to be for results in Illinois that result from the changes youŌĆÖve made.

JONAH EDELMAN

I think the soonest theyŌĆÖre going to able to make their year longer and their day longer would be January, and probably weŌĆÖre talking September, ŌĆś12. And you know, if you have a longer day but terrible teachers it doesnŌĆÖt do anything. You know, so itŌĆÖs about performance management, itŌĆÖs boring, itŌĆÖs not a silver bullet. But Jean-Claude Brizard needs to hire a lot of really good, what they call, chief area officers. HeŌĆÖs got to hire a lot of really good like superintentendent-level people. TheyŌĆÖd be overseeing 30 or 40 schools. And then theyŌĆÖve go to evaluate their principals rigorously and create much more of pipelines of quality principals. ItŌĆÖs blocking and tackling. But as Jim said, itŌĆÖs more conducive for folks. And I would think that more people would want to be prinicipals because I think now theyŌĆÖd realize that they not only have the accountability but the authority.

QUESTION 13

Do you want to have the accountability back to you, that that happens? I mean youŌĆÖve invested in this?

JAME SCHINE CROWN

OK, so the ŌĆ£youŌĆØ now shifts to a citizen of Chicago and these dire statistics. Which, IŌĆÖm glad, they seem to have had some shock value in this room. TheyŌĆÖve actually had steadily diminishing shock value, as people are just accepting these bad numbers and outcomes, like the weatherŌĆÖs tough in January too. Yes, weŌĆÖre interested in the transparency, weŌĆÖre interested in the metrics, weŌĆÖd very much would like this to happen. But thereŌĆÖs no single organization that can or should feel, this is all of us, as a citizen of Chicago as a citizen of the United States, you know, as Jonah said a minute ago, this conversation pertains to our future as a country, our financial well-being, our national security, and all these things are just going to meld together, and if this gets better, you know, weŌĆÖll be proud of helping it getting a little better.

OK, youŌĆÖre our last questioner, because weŌĆÖre coming to the end.

QUESITON 14

What was the role of media in this process? You know, generally speaking you try to bring media on board with you, but this sounds like it was a much more underground thing?

JONAH EDELMAN

No, IŌĆÖm glad you asked that. The Tribune was fantastic. I think they probaby wrote more than ten supportive editorials, prominent, top well written. I think Paul Weingarten was responsible for a lot of those. The Sun-Times was good. We had a lot of down state editorial support. It didnŌĆÖt become a big flashpoint, and so on the news side it didnŌĆÖt get so much attention. It did after it passed get a lot of attention. But editorial support was terrific, but I wouldnŌĆÖt call it anywhere near a decisive variable.

QUESTION 15

What about Wisconsin?

JONAH EDELMAN

Wisconsin was a problem for us. It made it hard for awhile. But we were able to reframe by doing a side-by-side, which we sent sent to all legislators juxtaposing our legislation from the Wisconsin legislation, to make clear that the unionŌĆÖs mantra of ŌĆ£this is a Wisconsin-style attackŌĆØ was baloney. But this is a charged media environment so I think to come out with this Kumbaya narrative was even more notable given the main story of polarization in the country.

JAME SCHINE CROWN

Thank you all for being here.

JONAH EDELMAN

Thank you.