The 1981 PATCO Strike August 3, 1981

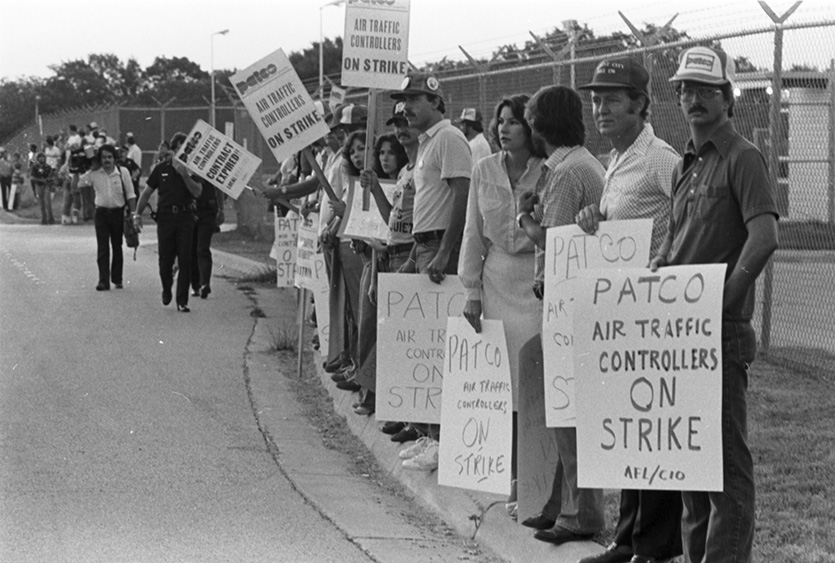

Group of people holding picket signs and standing in a picket line along the curb of a road with a metal fence in the background.

Group of people holding picket signs and standing in a picket line along the curb of a road with a metal fence in the background.

Air traffic controllers picket near a fence at DFW Airport's FAA tower during the PATCO strike. Aug. 5, 1981. (Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection)

On August 3, 1981, the majority of PATCO members went on strike, breaking a 1955 law that banned government employees from striking that had never previously been enforced.

On August 5, 1981, Reagan fired PATCO members who remained on strike and banned them from being rehired.

https://libraries.uta.edu/news-events/blog/1981-patco-strike In August 1981, over 12,000 members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) walked off the job after contract negotiations with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) broke down. President Ronald Reagan ordered them to return to work, and after 48 hours fired those who did not (Schalch).

The 1981 PATCO Strike

by Michael Barera

September 2 2021

https://libraries.uta.edu/news-events/blog/1981-patco-strike

PATCO was established in 1968 (Schalch, Lippert). During the 1970s, it was successful in using a series of slowdowns and sick-outs to gain retirement and retraining benefits for its members, air traffic controllers employed by the federal government, who were both at least 50 years old and had worked for at least 20 years (Lippert). In the 1980 presidential election, PATCO endorsed Reagan, who had previously been the president of the Screen Actors Guild, in his successful bid to defeat incumbent President Jimmy Carter. In a letter to PATCO president Robert Poli in October 1980, Reagan wrote "I pledge to you that my administration will work very closely with you to bring about a spirit of cooperation between the President and the air traffic controllers" (Pardlo).

PATCO began contract negotiations with the FAA in February 1981. Its main goals were a 32-hour work week, a $10,000 raise for all its members, and a better retirement package (Schalch, Lippert). At the time, PATCO members were making between $20,000 and $50,000 a year. In total, the value of the package that PATCO sought was $770 million, and the union rejected a counteroffer the FAA made that was worth $40 million in total (Glass). PATCO was also concerned about on-the-job stress for its members, as it reported that 89% of those who left air traffic controller jobs in 1981 were either retiring early and seeking medical benefits or leaving the profession entirely (Lippert, Pardlo).

Strike

Group of people holding picket signs and standing in a picket line along the curb of a road with a metal fence in the background.

Air traffic controllers picket near a fence at DFW Airport's FAA tower during the PATCO strike. Aug. 5, 1981. (Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection)

On August 3, 1981, the majority of PATCO members went on strike, breaking a 1955 law that banned government employees from striking that had never previously been enforced (Schalch). This law, which was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1971, allowed for punishments including fines and up to one year of jail time (Glass). However, while the law was on the books, a gentlemen's agreement had effectively been in place that prevented the firing of striking workers, which lead to no postal workers being fired during a strike in 1970 (Pardlo).

Reagan ordered the PATCO strikers back to work within 48 hours and declared the strike a "peril to national safety" (Schalch). He also ominously decreed that "there will be no negotiations and no amnesty" (Lippert). The Reagan administration additionally arrested a handful of PATCO leaders. Writing in The New Yorker, university professor (and son of a PATCO member) Gregory Pardlo argued that Reagan "treated the strike as a challenge to his authority" (Pardlo).

Over the course of the PATCO strike, a total of 7,000 flights were cancelled (Schalch). While the strike slowed air transportation around the country, it was not as disruptive as PATCO had hoped, as about 80% of flights remained unaffected (Glass). PATCO lost the public relations battle, too, as it was estimated that the public backed Reagan over the union by nearly a two-to-one margin (Lippert). Writing in The Baltimore Sun in 1991, Michael K. Burns argued that the lack of public support for the strike stemmed from both PATCO's demands being unattainable for most workers in the country and the disruption it caused for summer vacationers (Burns). Pardlo opined that the strike ultimately became "a fiasco of diminishing morale and failed public relations" (Pardlo). At its beginning, though, he noted that PATCO thought that its strike could work if it maintained 100% participation among its rank-and-file members, which it did not. Pardlo also opined that the strike caused the public to suffer "an inconvenience on the magnitude of a gas shortage or a natural disaster," and for that inconvenience, they squarely blamed PATCO (Pardlo).

On August 5, 1981, Reagan fired PATCO members who remained on strike and banned them from being rehired. He then began replacing them with a combination of about 3,000 supervisors, 2,000 non-striking air traffic controllers, and 900 military controllers (Glass, Schalch). The FAA began hiring new air traffic controller applicants on August 17, many of whom would later form a new union, the National Air Traffic Controllers Association (NATCA) (Schalch).

Aftermath

Cover of program with a drawing of Bourbon Street in New Orleans. The text of the program reads: "PATCO 14th Annual Convention, 1981, Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization, Fairmont Hotel, New Orleans, May 22-25."

Cover of PATCO's 14th annual convention program. The convention was held at the Fairmont Hotel in New Orleans, May 22-25, 1981. (Bill Taylor Papers)

On October 22, 1981, the Federal Labor Relations Authority (FLRA) decertified PATCO (Glass, Schalch). It became the first federal union to ever be decertified (Allabaugh). In June 1987, its de facto successor, NATCA (which had no connection to PATCO), officially became the only bargaining unit for air traffic controllers with the FAA (Glass, Schalch). Membership in NATCA is optional, but by 1991 roughly 70% of controllers were members (Lippert). PATCO was reformed in 1996 (Allabaugh).

In 1991, NATCA president Tom Murphy noted that the union's concerns were largely the same as those that lead PATCO to strike in 1981, namely salaries and stress levels (Lippert). Burns argued that NATCA was again fighting the same fundamental problems as PATCO a decade earlier: "under-staffing, overwork, antiquated equipment and sagging morale" (Burns). However, neither NACTA nor the FAA were willing to endure another strike after what had happened in 1981 (Burns).

The strike also caused an enduring shortage of air traffic controllers that extended into the George H. W. Bush administration, while a majority of the strikers had to settle for jobs that paid less (Burns). On August 12, 1993, President Bill Clinton ended Reagan's prohibition on rehiring PATCO strikers as air traffic controllers, and by 2006, roughly 850 of them had been rehired by the FAA (Glass, Schalch).

Legacy and analysis

Group of people sitting and standing around a table at a picnic. Cars and trees are in the background.

Otto Kruger and his family at a PATCO picnic. June 1, 1973. (James D. Wright Papers)

Historian Joseph McCartin observed that prior to the PATCO strike, the idea of employers firing their striking workers was almost universally seen as unacceptable, even though it was legal. One of the results of the 1981 strike was a sharp reduction in the annual number of major strikes, which dropped by an order of magnitude from an average of 300 per year before the PATCO strike (Schalch) to just 16 annually by the 2010s (McCartin). McCartin declared that PATCO's ill-fated strike was "one of the most important events" in late-20th century American labor history (Glass). This was partially because the "ability to strike played a key role in keeping wages in line with rising productivity," and after PATCO's strike this ability diminished considerably (McCartin). Another result was the stagnation of wages, which in 2021 McCartin calculated would have been $10 per hour higher had wages kept up with productivity over the past 40 years the same way they had before 1981 (McCartin).

Director of the Office of Personnel Management Donald J. Devine reported that numerous "private-sector executives have told me that they were able to cut the fat from their organizations and adopt more competitive work practices because of what the government did" in its handling of the PATCO strike (Glass). According to McCartin, numerous corporations, including Hormel, Phelps Dodge, and International Paper, provoked strikes among their employees and then hired replacement workers during the strikes to force major concessions upon unions (McCartin). In the estimation of Detroit Free Press labor writer John Lippert, Reagan's handling of the PATCO strike "hammered home to unionists that they were no longer honored guests in the nation's corridors of power" (Lippert).

McCartin called the Reagan administration's actions during the PATCO strike "the most ambitious and expensive act of strikebreaking in U.S. history" (McCartin). He also argued that the PATCO strike caused major political repercussions, as its results "disabled what was once a vital instrument for building and maintaining social solidarity and for directing inevitable class tensions and social conflict toward democratic and egalitarian ends" (McCartin). More concretely, he saw this as leading to a power vacuum that has encouraged white supremacy and enabled the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the United States Capitol (McCartin).

In McCartin's analysis, the trajectory from the 1981 PATCO strike to the January 6, 2021, insurrection illustrated that "the diminution of working-class power...is the crucial yet often overlooked element that has most imperiled our fragile, multi-racial democracy. It suggests that we will not be able to successfully defend democracy from those who would undermine it unless we also find ways to empower workers once again to defend their interests effectively through collective action" (McCartin).

As John Crudele argued in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1991, however, the PATCO strike was not the start of the decline of unionism in the United States. Changes in demographics, education, and the shift from manufacturing-based to service-based economies all contributed to the decline of unions prior to the strike. For instance, he observed that changes in the automotive industry alone had eliminated 800,000 union jobs by that point. In 1945, 35% of the nation's workforce was unionized, and by 1980, the year before the strike, this figure had fallen to 23% (Crudele). Labor's ties to the Democratic Party also hurt it during the Republican Party's control of the White House in the 1980s (Burns).

In 1991, Representative William Ford. a Democrat from Michigan, lamented that since the PATCO strike, "the wholesale replacement of strikers and the threat of permanent replacement have become epidemic" (Burns). The Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that 25% of employers hired or threatened to hire replacement workers during strikes in 1989, up from 15% just four years earlier (Burns).

In 2001, Ron Taylor, president of the reformed PATCO, called the 1981 strike "not in the best interest of anyone, but...a last resort" and considered its failure an "American labor tragedy" (Allabaugh). Taylor also argued that the focus on salaries and stress was largely due to the FAA's framing of the strike, while other issues such as equipment modernization and improving FAA management were neglected by PATCO, the media, and the public (Allabaugh).

Bibliography

Burns, Michael K. "10 Years After PATCO Strike, A Legacy of Labor Bitterness." The Baltimore Sun, August 4, 1991.

Crudele, John. "Decline Of Unionism Didn't Start With PATCO Strike." St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 3, 1991.

Glass, Andrew. "Reagan Fires 11,000 Striking Air Traffic Controllers, Aug. 5, 1981." Politico, August 5, 2017.

Lippert, John. "Decade later, strike haunts air controllers and labor." Detroit Free Press, July 28, 1991. (Continued as "PATCO strike haunts controllers and unions" on page 6G.)

McCartin, Joseph A. "The Downward Path We've Trod: Reflections on an Ominous Anniversary." Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor, Georgetown University, August 4, 2021.

Pardlo, Gregory. "The Cost of Defying the President." The New Yorker, February 12, 2017.

Schalch, Kathleen. "1981 Strike Leaves Legacy for American Workers." NPR, August 3, 2006.

By: John S. Whitfield

WORKER ORGANIZING WAVE

Warning: The Worker Organizing Wave is in Danger Because of Union Busting!

An Urgent Appeal For Unity and Mass Action

Sign on to get involved

The national wave of union organizing and militancy spearheaded by Starbucks workers and Amazon workers is the biggest upsurge in worker organizing since the 1930s and 1940s. The organizing wave has spread to Trader Joe’s, Chipotle, Apple, REI and a growing list of chain stores and industries.

However, this uprising of workers, which holds the potential of not only saving the labor movement, but transforming it, is under life-threatening attack. We must unite in defense of the brave young workers that are the vanguard of this transformative workers struggle.

WE PROPOSE THESE DATES FOR COORDINATED MASS ACTIONS Across The Country

*SEPT 5, Labor Day- Organize a presence at Labor Day marches or organize your own, (i.e., Amazon and Starbucks workers are planning to march in NYC)

*THURSDAY SEPT.8TH - A National Virtual Planning Meeting for the Days of Coordinated Mass Actions

*THURSDAY SEPT. 29 - National Coffee Day (a day often promoted by Starbucks)

*SATURDAY OCT. 1 - The six months anniversary of the Amazon Labor Union election victory on April 1 & International Coffee Day

The national wave of union organizing and militancy spearheaded by Starbucks workers and Amazon workers is the biggest upsurge in worker organizing since the 1930s and 1940s. The organizing wave has spread to Trader Joe’s, Chipotle, Apple, REI and a growing list of chain stores and industries.

However, this uprising of workers, which holds the potential of not only saving the labor movement, but transforming it, is under life-threatening attack. We must unite in defense of the brave young workers that are the vanguard of this transformative workers struggle.

From their corporate boardrooms down to their worksite managers, Starbucks and Amazon are engaged in an outright war to crush the organizing wave. Starbucks is firing union organizers, closing stores, cutting workers hours, and denying pro-union workers wage increases and benefits. Starbucks workers are fighting back. Starbucks Workers United is still winning union elections all over the country, and flexing its muscles with walkouts and strikes.

Amazon is determined to overturn the historic April 1st Amazon Labor Union victory in NYC, and crush the ALU. At the same time, new ALU chapters are forming around the country. The Amazon workers in North Carolina that have formed Carolina Amazonians United for Solidarity and Empowerment (CAUSE) are getting stronger everyday. Amazon workers everywhere, including in Amazonians United and the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union in Alabama, are coming together in spite of their different approaches to organizing. However, in order for these groundbreaking battles to defeat union busting, immensely greater forces must join and strengthen them.

Howard Schultz and Jeff Bezos are this year's poster boys for union busting. But efforts to crush the workers’ uprising are by no means limited to Starbucks and Amazon. Wall Street, and the U.S. capitalist class are fully behind this war to destroy a new workers movement before it spreads further.

Our response to this threat must be equal to the danger. It is going to require a level of mass solidarity and mass mobilization in defense of workers on the frontline greater than anything that we have seen in our lifetimes. Unified organizing and widespread mass solidarity is absolutely central to the continuation of this historic transformation of the working class movement.

At stake is nothing less than the long awaited and necessary evolution of the working class movement from its present weak state to A MORE RADICAL, MILITANT, INCLUSIVE, AND CLASSWIDE MOVEMENT THAT:

Is lead by rank and file workers

Is not dominated by business unionism

Is not dependent upon or subservient to the Democratic party

Views all struggles as workers struggles, including the fight against racism, access to abortion, the antiwar struggle, the struggle to stop climate disaster, the struggle for LGBTQ2S+ rights

Is a vital part of the struggle against evictions and all community struggles

Prioritizes the most oppressed workers, including migrant workers

Wants to be part of a militant global workers movement

Is strong enough to smash the threat of fascism

A growing section of the left is now engaged in varying levels of solidarity work with these critical workers struggles. But as of yet, the left's commitment to this struggle is alarmingly insufficient. While some in the organized labor movement are taking the need for solidarity against union busting seriously, unfortunately, most of the top leadership of the labor movement remain unmoved by this threat, and have focused on electoral politics and reliance on the Democratic Party. This is not good and it must change. Now’s the time to intensify the pressure to compel that change.