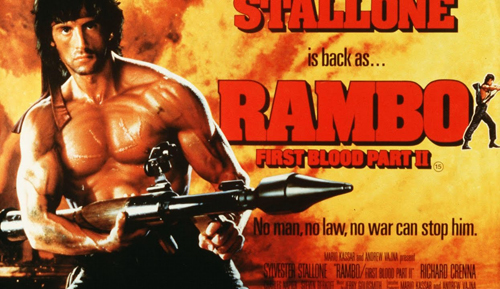

'Spitting' lies still loom large in Ken Burns's 'Vietnam'... History as written, in part, by the cowards like Sylvester Stallone ('Rambo') and others who lived the 'Draft Dodger Rag'...

After dodging the Vietnam War Draft from the safety of an expensive private school for rich kids in Switzerland, Sylvester Stallone returned to the safety of the post-Vietnam War USA to begin a career as a shameless propagandist for the whitewashing of history on behalf of U.S. imperialism's version of Vietnam. The "Rambo" movies perpetuated both the "spitting Hippie" and the MIA lies that continue to this day in the wake of the facts of the shameful American war in Vietnam. Stallone was not the only coward who later profited from the lies about that war, but he is certainly among the most noteworthy because of his propaganda work in the "Rambo" films.Aware that a Ken Burns video about a part of our history is likely to become a major piece of the curriculum by means of which American children (including my own) learn the "lessons" of Vietnam, I've watched the whole thing twice. And following the second viewing, even giving credit to Burns for including the experiences of so many Vietnamese, my conclusion is that Burns has still succumbed to lies of the Reagan Era and since -- the "Rambo" version of what happened. Teachers are going to have to sort through the facts of the Vietnam War despite the overwhelming heat of the propaganda that swirls through official versions of American history.

After dodging the Vietnam War Draft from the safety of an expensive private school for rich kids in Switzerland, Sylvester Stallone returned to the safety of the post-Vietnam War USA to begin a career as a shameless propagandist for the whitewashing of history on behalf of U.S. imperialism's version of Vietnam. The "Rambo" movies perpetuated both the "spitting Hippie" and the MIA lies that continue to this day in the wake of the facts of the shameful American war in Vietnam. Stallone was not the only coward who later profited from the lies about that war, but he is certainly among the most noteworthy because of his propaganda work in the "Rambo" films.Aware that a Ken Burns video about a part of our history is likely to become a major piece of the curriculum by means of which American children (including my own) learn the "lessons" of Vietnam, I've watched the whole thing twice. And following the second viewing, even giving credit to Burns for including the experiences of so many Vietnamese, my conclusion is that Burns has still succumbed to lies of the Reagan Era and since -- the "Rambo" version of what happened. Teachers are going to have to sort through the facts of the Vietnam War despite the overwhelming heat of the propaganda that swirls through official versions of American history.

Those who aren't familiar with the actual history and get too much of their "history" from Hollywood don't remember that Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, and George W. Bush aren't the only members of my generation who dodged the draft and also avoided opposing the war. Clinton kept getting college deferments, Trump had "bone spurs" which seem to have disappeared, and Bush was in the Texas National Guard during the years when the National Guard guarded the home front -- but was never sent out of the USA to fight in Vietnam. All of them, each in his own way, could have merited a stanza in Phil Ochs's wonderful "Draft Dodger Rag."

But few match Sylvester Stallone for hypocrisy. As close readers of history know, Stallone spent his "war years" safely in a wealthy kids' private school in Europe.

But once the war was over, Stallone was ready to fight for the revisionist histories of what he had avoided, and so the world got the lies of "Rambo." To hear Stallone's fictional character tell it, all American GIs fought the good fight bravely, were betrayed by those behind the lines, and then came home to be spit upon by anti war "Hippie" protesters. Of course, Stallone's version of the Vietnam War and post Vietnam is not the only Hollywood myth about the Vietnam War, and the Ken Burns curriculum will probably not be the last. But it's worth reading the article below -- and several important books -- if children growing up in 2017 are going to have a chance of avoiding the Fake News that is being passed along from those who dominate American culture about the Vietnam War. (And while we're at it, what was Harvey Weinstein, who was of draft age too during Vietnam, doing in 1967?).

[Disclosure: I was the first (and perhaps the only) young man to become a I-O conscientious objector from the Elizabeth New Jersey draft board and I spent the years after 1968 -- when I got that I-O -- doing military law, counseling, and organizing with soldiers, sailors, Marine and airmen who became the "G.I. Movement" that really ended the Vietnam, War by doing a general strike against that war by those men and women who were designated to fight it. That's why we now are free of the Draft and why there is still a fear in the hearts of the American ruling class about resuming the Draft or expanding any foreign war too far. For those who want more about that, you can watch Sir No Sir! or read Soldiers in Revolt. But for today, the recent article below tells an important part of the story.]

The Myth of the Spitting Antiwar Protestor

Jerry Lembcke

October 13, 2017

New York Times

The war in Vietnam was America’s longest war at the time, and its first defeat. The image of protesters spitting on troops enlivened notions that the military mission had been compromised, even betrayed, by weak-kneed liberalism in Congress and seditious radicalism on college campuses. The spitting stories provided provided reassuring confirmation that had it not been for those duplicitous fifth-columnists, the Vietnamese would have never beaten us.

“So where do these stories come from?”

The reporter was asking about accounts that soldiers returning from Vietnam had been spat on by antiwar activists. I had told her the stories were not true. I told her that, on the contrary, opponents of the war had actually tried to recruit returning veterans. I told her about a 1971 Harris Poll survey that found that 99 percent of veterans said their reception from friends and family had been friendly, and 94 percent said their reception from age-group peers, the population most likely to have included the spitters, was friendly.

A follow-up poll, conducted in 1979 for the Veterans Administration (now the Department of Veterans Affairs), reported that former antiwar activists had warmer feelings toward Vietnam veterans than toward congressional leaders or even their erstwhile fellow travelers in the movement.

I was glad the reporter was interested in the origin of these stories, because beginning even before the war ended, news organizations had too often simply repeated them — even though some stories had the hallmarks of tall tales all over them. Even The Times once quoted, matter-of-factly, a veteran telling of how he arrived stateside from Vietnam on a stretcher with a bullet in his leg, only to be splattered with rotten vegetables and spat on by antiwar college kids.

Whoppers like these go unchallenged by reporters and scholars perhaps because of their memoirist first-person quality, stories told by the men who say it happened to them. I collect the stories, I told the reporter, and have a spreadsheet with about 220 first-person “I was spat on” accounts.

But you don’t believe the stories, right? she asked.

Acknowledging that I could not prove the negative — that they were not true — I went on to say there is no corroboration or documentary evidence, such as newspaper reports from the time, that they are true. Many of the stories have implausible details, like returning soldiers deplaning at San Francisco Airport, where they were met by groups of spitting hippies. In fact, return flights landed at military air bases like Travis, from which protesters would have been barred. Others include claims that military authorities told them on returning flights to change into civilian clothes upon arrival lest they be attacked by protesters. Trash cans at the Los Angeles airport were piled high with abandoned uniforms, according to one eyewitness, a sight that would surely have been documented by news photographers — if it had existed.

And some of the stories have more than a little of a fantasy element: Some claim the spitters were young girls, an image perhaps conjured in the imaginations of veterans suffering the indignities of a lost war.

Listeners, I speculated, are loath to question the truth of the stories lest aspersion be seemingly cast on the authenticity of the teller. The war in Vietnam was America’s longest war at the time, and its first defeat. The loss to such a small, underdeveloped and outgunned nation was a tough pill for Americans to swallow, many still basking in post-World War II triumphalism. The image of protesters spitting on troops enlivened notions that the military mission had been compromised, even betrayed, by weak-kneed liberalism in Congress and seditious radicalism on college campuses. The spitting stories provided reassuring confirmation that had it not been for those duplicitous fifth-columnists, the Vietnamese would have never beaten us.

“The war at home” phrase captured the idea that the war had been lost on the home front. It was a story line promulgated by Hollywood within which veteran disparagement became a kind of “war story,” a way of credentialing the warrior bona fides of veterans who may have felt insecure about their service in Vietnam. In “First Blood,” the inaugural Rambo film, the protagonist, John Rambo, flashes back to “those maggots at the airport, spittin’, callin’ us baby killers and all kinds of vile crap.” The series supported the idea that decisions in Washington had hamstrung military operations. “Apocalypse Now” fed outright conspiracy theories that the C.I.A.’s secret war run from Washington had undercut the military mission. “Coming Home” and “Hamburger Hill” played on male fears of unfaithful wives and girlfriends, a story line hinting that female perfidy and the feminist subversion of warrior morale had cost us victory.

Women had been prominent in the opposition to the war. Two organizations, Women Strike for Peace and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, led early protests; Cora Weiss, Jane Fonda and Joan Baez lent their social and celebrity standing to the efforts to end the fighting. New Left organizations such as the campus-based Students for a Democratic Society intersected with the burgeoning women’s movement to boost young women into leadership roles in the antiwar movement. Placards reading “Girls Say Yes to Boys Who Say No” — no to the draft, that is — lent credence to the fears of conservatives who were pro-war and distraught over loosening strictures on premarital sex and believed that the rising of the women meant societal collapse.

The adoption of long hair, embroidered shirts and bell-bottom pants, and general rejection of military bearing by men in the movement evinced a softening of conventional sex-gender boundaries. By the late 1960s, troops in Vietnam were battling authorities over hair length, and the right to wear love-bead necklaces and draw peace symbols on their helmets.

Finger pointing for the loss of the war began even before it was over. The pacifists and radicals who stoked the antiwar movement were easy targets for the patriotic right wing looking for scapegoats, but the visibility of women in the resistance to the war made them suspects as well. After Ms. Fonda went to North Vietnam on a peace mission in 1972, she was denounced as a traitor in profanely sexist language and tarred as “Hanoi Jane.” Years later, the feminist author Susan Faludi wrote that fears of emasculation having cost America its victory in Vietnam were the basis of a backlash against women in the 1980s.

But, the reporter pressed, why spitting? Resisting the urge to plunge into the Freudian exegesis I wanted to take, I pointed to the long history of spitting imagery in legends of betrayal. In the New Testament, Christ’s followers spit on him in renunciation of their loyalty. Following Germany’s defeat in World War I, soldiers returning from the front claimed to have been spat on by women and girls. The German stories were studied by historians and found to be part of the “Dolchstosslegende,” or stab-in-the-back legend, that the military had been betrayed behind the lines, sold out at home.

Anticipating the question, I agreed that the presence of such stories in religious teachings and myths only pressed more questions to the fore about where the biblical Apostles and German folklorists got them, questions that will keep professors and students of cultural studies occupied for years.

But, I ventured, where the stories go — how they play out in the political culture — is more important than where they come from. The reporter seemed interested. In Germany, I recalled, the imagery of shellshocked World War I veterans became a stand-in for the nation’s lost pride and damaged sense of racial superiority. The riffs of betrayal in the photographs, films and news reports of veterans made victims by war kept alive the certainty that enemies outside the gates could never defeat a rearmed and unified Germany; the stories incited a dangerous witch hunt that led to the Holocaust.

Is the abiding American discomfort with the war it lost in Vietnam and the enduring allure of the spat-upon veteran stories indicative of betrayal preoccupations at work in our own culture? Is it the post-Vietnam lost-war narrative that feeds the back-to-the-future sentiments in campaign promises to restore and rebuild America? And are the recent public and political spectacles of nativism and gun-toting masculinity symptoms of a wounded people more than deviant personalities?

The reporter was interested.

Jerry Lembcke, an associate professor emeritus at College of the Holy Cross, is the author of “The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam and Hanoi Jane: War, Sex, and Fantasies of Betrayal.” In 1969 he was a chaplain’s assistant assigned to the 41st Artillery Group in Vietnam.

By: BrandonBag

rescue remedy stress

lip sores remedies https://forums.dieviete.lv/profils/127605/forum/ fibroid remedies