BLACK HISTORY MONTH LESSON PLAN: How Rahm Emanuel is in the Chicago tradition of Sewell Avery as a traitor to the best in the USA

Why should a 28-part Substance series on Black History Month begin with a famous white capitalist from Chicago? Because from the day the first slave ship sailed to West Africa to bring back a �cargo� of a human commodity, there has been an intimate relationship between capitalism and un-freedom (to play back against the words of Milton Friedman�s notorious reality distortion field, Capitalism and Freedom). And so� after this episode, we will devote time to ten African Americans (we�ll be calling them �Black People� from now on, because several of them were not Born in the USA) for Black History Month � recovered.

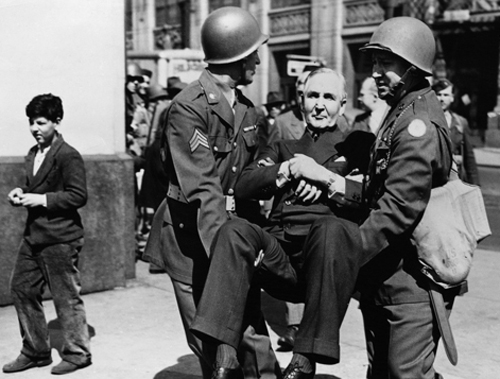

Sewell Avery being carried out of the headquarters of Montgomery Ward.Like most CEOs during the New Deal, Sewell Avery of Montgomery Ward opposed the New Deal and considered Franklin D. Roosevelt a Bolshevik. And like most of his owning-class peers, Avery was a quasi-supporter of fasiscm, first Italy's version, then the big one that took over Germany from 1933 on. Not all American capitalists like fascism -- just the majority. And their long tradition of sacrificing all human values to the "bottom line" had given them dozens of philosophical and other pretexts for their beliefs.

Sewell Avery being carried out of the headquarters of Montgomery Ward.Like most CEOs during the New Deal, Sewell Avery of Montgomery Ward opposed the New Deal and considered Franklin D. Roosevelt a Bolshevik. And like most of his owning-class peers, Avery was a quasi-supporter of fasiscm, first Italy's version, then the big one that took over Germany from 1933 on. Not all American capitalists like fascism -- just the majority. And their long tradition of sacrificing all human values to the "bottom line" had given them dozens of philosophical and other pretexts for their beliefs.

The best recent account of the confrontation that led to Avery being carried out of his offices on Chicago Ave. by soldiers in 1944 was published in Bloomberg Business Week two years ago. It's worth checking out the history of the guy who skirted treason during the Second World War because he was a fanatical believer in the religion and theology of capitalism and the so-called "free market."

BLOOMBERG BUSINESS WEEK STORY...

When the Army Invaded Montgomery Ward, By Kenneth Lipartito, Bloomberg Business Week Dec 7, 2012 12:16 PM CT

Many corporate executives have defied the government. How many have been willing to be carried from their offices by soldiers for doing it?

Sewell Avery was. In 1944, Avery, the head of retail giant Montgomery Ward, was ordered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to settle a strike with his workers. When he refused, the government took over his company. In an iconic photo of the era, two soldiers hold Avery in a sitting position, his arms crossed, a look of insubordination on his face, as they remove him from the building.

Although the company was eventually returned to private hands, Avery didn�t relent in his opposition to Roosevelt or the New Deal. He continued to combine business with politics. The mixture didn�t go well for him, or for his company.

Avery was born into a prominent family in Saginaw, Michigan. He got his start managing a small gypsum plant, which was folded into the United States Gypsum Co. (USG) in 1901. Avery worked his way up to president within a few years.

In the depths of the Great Depression, he took charge of the struggling retailer Montgomery Ward. Founded in 1872, the company had pioneered catalog sales but had steadily lost ground to its Chicago rival Sears Roebuck & Co. Avery slashed costs, fired workers, closed stores and reduced lines. The strategy worked and the company�s finances soon rebounded.

Robbing Liberty

But even as the country began to recover from the Depression, and Avery�s personal wealth soared, he remained convinced the economy was on the path to ruin. He kept generous cash on hand at Montgomery Ward, fearing the destabilizing effects of government policies. A fierce proponent of free markets, he opposed Roosevelt�s seemingly pro-business National Recovery Act, which allowed industries to set prices and control output, and he held out against labor unions, convinced that in resisting these �robbers of liberty� he was speaking to the �hearts of millions.�

He helped to finance anti-Roosevelt groups and urged Montgomery Ward�s shareholders to vote in the 1935 election to end �burdensome and inequitable taxes,� which he said were holding back business expansion.

Such fulminations pitted Avery against a popular president who won re-election by overwhelming majorities in 1936 and 1940. And when the nation entered World War II, his battle took on national-defense implications.

In 1942, Roosevelt reauthorized the World War I-era War Labor Board. Composed of business, political and union leaders, the board arbitrated labor disputes to prevent any slowdown of production. Unions agreed not to strike for the duration of the war, so long as management agreed to abide by the board�s decisions.

This didn�t sit well with Avery. When his employees sought to unionize, he declined to recognize them, incensed particularly by a maintenance-of-membership clause in their proposed contract. New workers would be automatically enrolled in the union after 15 days, a concession the government granted in exchange for the pledge not to strike. Avery viewed it as the first step toward a �closed shop.�

The conflict simmered for almost two years, then came to a boil on April 27, 1944, when the company�s labor agreements expired. Without a contract, the workers weren�t bound by the no-strike pledge. Roosevelt ordered Avery to either extend the contract pending a union-certification vote or accede to government seizure of his company.

Feet First

When Avery refused, soldiers arrived and took him out the door. On his way out, Avery allegedly could be heard shouting something to the effect of �You New Dealers, you.� Softening his tone a bit later, he affirmed his support for the war effort and joked, �I�ve been fired before, but this is the first time they ever carried me out feet first.� Nonetheless, he was steadfast that his actions were a protest against �political slavery.�

The case quickly made it to the courts. As the judge deliberated, Montgomery Ward was nominally being run by the U.S. Department of Commerce. Before a ruling could be handed down, however, the union completed its election and employees returned to work. On May 9, Commerce Secretary Jesse Jones returned the company to private management.

Avery still wasn�t placated. He rejected the union contract, and by December the labor situation had deteriorated once more. Workers in Detroit and Chicago again went on strike. On Dec. 27, 1944, the president ordered the War Department to take over.

This time Avery stayed in his executive suite, while Major General Joseph Byron and his staff made do with an office nearby. The general and the chief executive officer traded control of Avery�s reserved parking space, depending on who arrived first. Avery and his team engaged in a sort of passive resistance, refusing to show where the company books were kept or to aid in their use. The general warned that employees could be dismissed for noncompliance and then reclassified for active service by their draft boards.

While the government argued that Avery�s actions imperiled the business-labor accord, Avery countered that the War Labor Board was merely an advisory body and that his company wasn�t a war-production facility. The issue ended up back in federal court for months. Finally, on Oct. 18, 1945, the Army relinquished control once more.

The fight with Roosevelt hardened Avery�s resolve against liberalism. He purged company managers who opposed his view, and Montgomery Ward entered the postwar decades with Avery, at 76, running a one-man show. He criticized companies that offered their workers frills like pensions and decried the public�s taste for security above risk. Sure that the economy was headed toward collapse, he again stockpiled cash and refused to follow rival retailer Sears Roebuck on a course of growth and expansion. As consumers moved to the suburbs in the 1950s, Avery and Montgomery Ward stuck with their aging downtown stores.

Montgomery Ward rallied a number of times over the next four decades, but its best days were over. In 2000, the company closed its doors for good. Only the name survives, purchased by an online retailer.

Avery died in 1960 a wealthy man, a beneficiary of the boom he denied was happening. But his efforts to turn the tide of politics were a failure. �Who am I to argue with history?� he once quipped to critics. Argue with history he did, however, and it cost his company the future. It�s a lesson for shareholders to consider if their CEO is thinking of Going Avery.

(Kenneth Lipartito is a professor of history at Florida International University and co-author of �Corporate Responsibility: The American Experience.� The opinions expressed are his own.)

By: Theresa D. Daniels

A Truly Funny History Lesson, George

I really appreciate your expose here of yet another prince of capitalism. You can't make this stuff up, it's so funny. People need to learn about the antics of our most powerful. Their balloons need to be burst, so we can all stop our admiration of their despicable characters and lives.