STRIKEWATCH: Should Your Teacher Strike? (Or your Mailman? Fireman? Sanitation man? Policeman?) May 1970, American Federation of Teachers. A Teaching Unit on Rights of Public Employees

With the Chicago Teachers Union drawing closer to a strike (possibly as early as the first week of September 2012), Chicago teachers, parents and students are asking more and more questions about the legalities and realities of strikes by teachers (and other public workers) in the USA. On one level, it is a question of rights. Workers in the USA establish their rights by winning fair contracts that we can enforce. At times, these contracts must be won by striking.

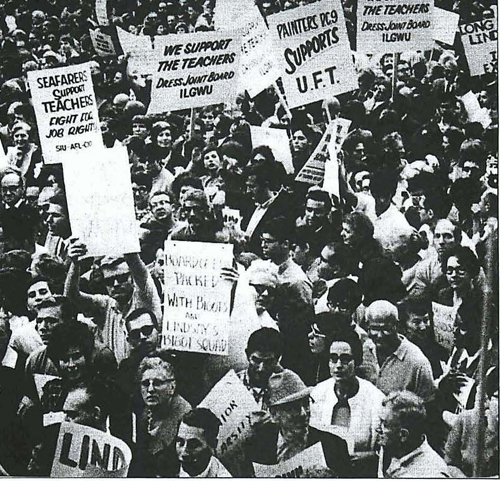

Above, members of various New York unions turned out to support the striking New York City teachers (the United Federation of Teachers, Local 2 AFT; CTU is Local 1) during the 1960s. Photo courtesy of the American Federation of Teachers.One of the things teachers can do is teach. And one of the subjects teachers can teach is labor history — and the facts about strikes and striking.

Above, members of various New York unions turned out to support the striking New York City teachers (the United Federation of Teachers, Local 2 AFT; CTU is Local 1) during the 1960s. Photo courtesy of the American Federation of Teachers.One of the things teachers can do is teach. And one of the subjects teachers can teach is labor history — and the facts about strikes and striking.

The past quarter century or so may be the era of the scab and the rule of the union busters, but it was not always that way. During the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, American teachers, often led by the example of Chicago teachers, went on strike for our rights and won major victories with each strike. By the end of the 1980s, Chicago teachers had won decent pay and benefits, seniority rights to rehiring. Yes, by the early 1990s all Chicago teachers — including full time substitutes — had the right to be hired back to full-time jobs in the even of layoffs or school transformations. (These rights were surrendered by union leaderships under four presidents between 1994 and 2010; seniority was not just taken away — it was given away! Another history of that sad reality is being prepared by Substance reporters and editors for another chapter of STRIKEWATCH to be entitled, "from Militant Unionism to Company Union...").

In order to teach it, we have to know it ourselves. Regularly this summer at substance we are publishing STRIKEWATCH to help both our fellow CTU members, parents, and students understand what is about to happen and why.

The past fourteen months have been striking. At no time in Chicago history has a mayor attacked teachers, our union, and the public schools so relentlessly as Rahm Emanuel has since May 2011. That history, going back to Emanuel's first act — breaking the old union contract and stealing $100 million in a raise due to all CPS workers in June 2011 — continues through today. The historical facts begin with the June 15, 2011 claim by the Board that it couldn't afford the four percent raise guaranteed in the union contract, continued through the entire "Longer School Day" attacks by the mayor and his apologists, and went on and on throughout the year. School closings in February 2012 reached their highest level ever, and the Board promised not only more closings, but more charter schools.

By the end of the 2011 - 2012 school year there were dozens of reasons why 10,000 Chicago Teachers Union members rallied and marched on May 23, 2012 — then voted more than 90 percent to authorize a strike between June 6 and June 8, 2012.One word more than any other states the "Why" for the past 14 months: Rahm Emanuel. But the policies being pushed by Rahm Emanuel's seven school board members and top CPS executives are the policies of a social and economic class (now generally known, thanks to the Occupy movement, at the "one percent"). As history shows, no one man, no matter how offensive, is the complete problem.

As part of STRIKEWATCH, Substance published a classic pamphlet once widely circulated by our national union, the American Federation of Teachers (AFT). Note that the AFT material below is 42 years old. The books and the movies available on strikes have been extended. Some of the material is dated, but it is interesting that so much of it reads like current events.

In a future STRIKEWATCH, Substance will expand these lists of books and movies. And we are preparing a new list, made possible by the plutocratic attack on unions during the past quarter century, called "Scab movies from Marva Collins and Jaime Escalante to Ken Burns and Geoffrey Canada". Scab movies have been one of the mainstays of plutocratic propaganda for the past quarter century, and Rahm Emanuel's Hollywood roots are well known. For more than a year, Chicago teachers and other school workers have been the victims of some of those union busting, teacher bashing, and privatization scripts — from "Longer School Day" to "Charters are Better" and "Yours is a Failing School."

For now, teachers might want to watch the movies Matewan or Norma Ray, both about union organizing, and take a look at all the Scab movies (which will also be reported in STRIKEWATCH in the coming weeks) from "Stand and Deliver" to the final "inning" on Ken Burns's "Baseball" and "Waiting for Superman." Scab propaganda has increased since the last Chicago teachers strike in 1987.

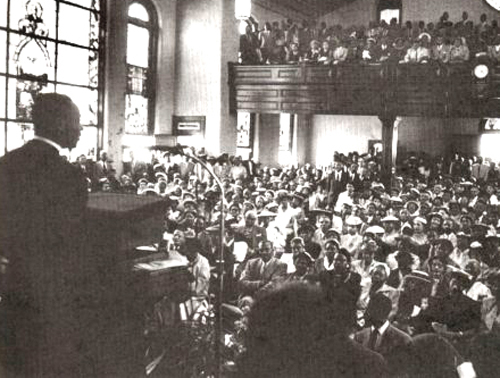

Although the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is honored throughout the world, in the USA there is a careful editing of King's life and work. Ignored in many of the plutocratic accounts of King's work is the fact that his life was ended by an assassin's bullet while he was in Memphis helping a strike of garbage workers, all of whom were black. Above, King is seen delivering his final sermon at the Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 3, 1968, was the last public appearance before his assassination the next day. King, in Memphis to support a strike by garbage workers, gave a poignant vision of the victorious future of the civil rights struggle, but without him there to witness its final triumph. To many in the audience and beyond, King’s speech seemed to predict his own death. King's sermon, to many more poignant than his "I have a dream" speech, is reprinted in total at the end of the article accompanying this photograph.Chicago teachers and others should also know that in Illinois collective bargaining and strikes by teachers are legal. Although SB 7 tried to make it impossible for the Chicago Teachers Union to strike in 2012 (and Rahm Emanuel tried desperately, almost to the point of tears, to get a complete ban on CTU strikes in Springfield in the Spring of 2012 when he realized that the CTU would jump the legal hurdles of SB7), massive organizing and deft legal work by the leaders, lawyers and members of the Chicago Teachers Union cleared all the obstacles to a successful contract negotiations — or the necessity of a strike.

Although the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is honored throughout the world, in the USA there is a careful editing of King's life and work. Ignored in many of the plutocratic accounts of King's work is the fact that his life was ended by an assassin's bullet while he was in Memphis helping a strike of garbage workers, all of whom were black. Above, King is seen delivering his final sermon at the Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 3, 1968, was the last public appearance before his assassination the next day. King, in Memphis to support a strike by garbage workers, gave a poignant vision of the victorious future of the civil rights struggle, but without him there to witness its final triumph. To many in the audience and beyond, King’s speech seemed to predict his own death. King's sermon, to many more poignant than his "I have a dream" speech, is reprinted in total at the end of the article accompanying this photograph.Chicago teachers and others should also know that in Illinois collective bargaining and strikes by teachers are legal. Although SB 7 tried to make it impossible for the Chicago Teachers Union to strike in 2012 (and Rahm Emanuel tried desperately, almost to the point of tears, to get a complete ban on CTU strikes in Springfield in the Spring of 2012 when he realized that the CTU would jump the legal hurdles of SB7), massive organizing and deft legal work by the leaders, lawyers and members of the Chicago Teachers Union cleared all the obstacles to a successful contract negotiations — or the necessity of a strike.

The following literature is from May 1970 supplied by the American Federation of Teachers to support the many locals that were striking in the 1970's.

Should Your Teacher Strike? (Or your Mailman? Fireman? Sanitation man? Policeman?) May 1970, American Federation of Teachers. A Teaching Unit on Rights of Public Employees

Introduction

Nearly one of every six workers in the United States today is employed directly by the government.

You know many of them. Teachers, principals, custodians, and other educational workers make up the biggest chuck. Leave your school and you find more: the policeman on the corner beat, a census taker, a clerk in the post office, your mailman, a fireman, a museum guide, a nurse, a social worker, the lifeguard at the beach.

Altogether, there are 12.5 million public workers in the country, out of a total work force of just over 80 million. In most respects, they’re like all the other workers in the U.S. – they perform useful services or provide necessary products, they get paid for their work, and they have bosses.

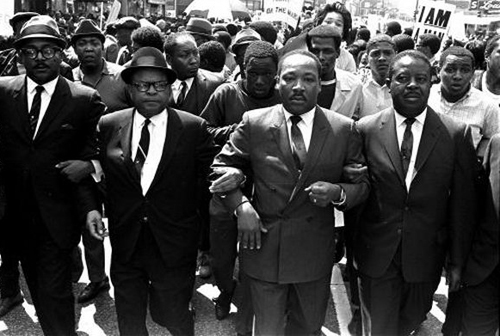

On March 28, 1968, one week before he was murdered, Martin Luther King Jr. led a march on behalf of the striking sanitation workers of Memphis. The workers carried signs that read "I am a man." But in one major respect, they’re different. They usually can’t bargain for wages and working conditions in the same way that privately employed workers can, and they almost never have the legal right to strike.

On March 28, 1968, one week before he was murdered, Martin Luther King Jr. led a march on behalf of the striking sanitation workers of Memphis. The workers carried signs that read "I am a man." But in one major respect, they’re different. They usually can’t bargain for wages and working conditions in the same way that privately employed workers can, and they almost never have the legal right to strike.

This teaching unit examines the rights of public workers. It was conceived during what most certainly has been the greatest upsurge of militancy among public workers in the nation’s history. In the past several months, the city of San Francisco was virtually shut down by public-employees’ strikes, the air traffic controllers’ actions seriously curtailed transportation, mail was delayed by postal strikes, and, of course, teacher strikes continued unabated. The past few months have also seen rising reaction by government: AFT President David Selden and 200 teachers in Newark, N.J., all of whom violated an ex parte antistrike injunction, were sentenced to up to six months in prison. The federal government called out troops to keep the post offices functioning. Congressmen reacted to a threatened walkout by District of Columbia teachers by postponing action on a teacher-pay bill. Air traffic controllers were summoned to court for contempt proceedings. Threats have been made to fire the firemen.

This teaching unit – prepared by labor historian Will Scoggins at the AFT’s request – ought to capitalize on the interest aroused by all these recent events, and promote class discussions on the rights of public workers. It is not a one-sided presentation, nor is it a programmed, here’s-how-to-do-it, readymade plan that you can take into your class and start using immediately. It requires that you do some reading, some homework, and some creative lesson planning on your own. It is divided into three suggested lessons, preceded by an overview. Each lesson has it’s own goals, suggestions for class discussions, and some proposed activities. You may wish to introduce the unit by dissecting a recent teachers’ strike in your district or a nearby district, or by talking about the postal strikes or other strikes of public workers that have directly affected your students.

However you use it, we’d like to hear from you. How did you build on this unit? How did your students respond? Let us know. We’ll share the most interesting experiences with American Teachers readers in a future issue. And if you’d like more copies of this teaching unit to share with non-AFT members, please write to us. We’ll be happy to send you more.

Overview

Background for Teachers

It is a matter of public record – via polls, newspapers and letters from readers of newspapers, scholarly studies, and television interviews, as well as our own experience in our classroom – that there exists a great deal of misinformation, prejudice, and outright hostility concerning the organization of workers into unions and their subsequent collective action to improve their lot. Why this should be so is not the immediate subject of this teaching unit. That the negative attitudes exist, however, and that the hostility seems greater toward workers in the public sector (garbage collectors, municipal bus drivers, postmen, teachers) when their actions necessitate a slowdown or interruption of services than when workers in the private sector do the same thing, should be known to every teacher. He can then begin to prepare himself to deal with it and attempt to dissipate the hostility and correct the misinformation.

Labor-History Unit

We assume that the teacher – especially a teacher of social studies – already presents a relatively comprehensive unit on the overall subject of labor-management history and of the protagonists’ relations with each other. Such a unit stresses the changes in the nature of employment resulting from the industrial revolution and the organization of capital within the corporate structure into larger and larger units to defend its interest within the economy.

The teacher need not shrink from the clearly documented violence of the clash between labor and management that marks much of American history from 18790 to 1940. After all, it is nothing short of illusion to believe that the interests of the contesting groups are the same, or necessarily even complementary. The adversary relationship does exit. However, the teacher might be wise, especially given the treatment of most U.S. history textbooks concerning this violence, to demonstrate that the collision of interests was only a part of the overall working-out of the concept of industrial democracy, the rights of workers to the protection of their lives and skills, and a way of guaranteeing them as well as their employers an adequate share of the wealth that they, jointly, have created.

The teacher might also present a more comprehensive treatment than is found in most textbooks of the important of the three major federal laws governing the maturing relationships between labor and management. The Wagner Act (1935), the Taft-Hartley Act (1947), and the Landrum-Griffin Act (1959) have spelling out in detail the rights as well as responsibilities of the contestants and have provided the machinery whereby the overwhelming majority of conflicts can be resolved peacefully.

Collective Bargaining

The most important method, and one that although no longer unique to America was an American innovation, is that of collective bargaining. The Labor-Management Relations Act as amended defines it simply: (Sec. 8 d) “To bargain collectively is the performance of the mutual obligation of the employer and the representative of the employees to meet at reasonable times and confer in good faith with respect to wages, hours, and other terms and conditions of employment.” A whole course of study might be constructed on the implications of this definition alone!

However, we are dealing in this proposed unit of instruction with a more sophisticated problem. During eighty years of collection action, and finally of law, the relationship between labor and private employers has been worked out fairly explicitly.

A Different Story

The Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932 guaranteed freedom of organization to workers in private industry. It forbade courts to issue injunctions for a number of union actions, including work stoppages. Before an injunction could be issued, a hearing would have to be held in open court and the finding would have to be that unlawful acts has been threatened and would be committed, that substantial and irreparable damage to property would occur for which there was no adequate remedy at law, or that public officers were unable or unwilling to protect private property.

“No Place” For Militancy?

But what happens when the worker happens not to be employed by a private corporation, but by a public agency – a government, federal, state or local, or a school board? President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave his answer thusly in 1937: “The process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service. …The employer is the whole people who speak by manes of laws enacted by their representatives in Congress. …Particularly, I want to emphasize my conviction that militant tactics have no place in the functions of any organization of government employees.”

Moreover, Congress purposely excluded federal employees from coverage under the Wagner Act of 1935 and the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947. Furthermore, Public Law 330 of 1955 makes it a felony for federal employees to strike or even assert the right to strike.

The issue raised here is the age-old one of the sovereignty of the state, or more precisely, of the government. It has been asserted that sovereignty, in practice, finds expression in the processes of making decisions accompanied by authority, decisions regarded as binding on the community and ultimately enforceable. Would not the extension of negotiable rights to employees of the sovereign thereby diminish sovereignty itself? And since, theoretically, in a democratic state the sovereignty rests ultimately with the people, then would not the extension of those rights result in a sacrifice of the rights of the people, or a collision with the “public interest?”

As stick as this logic may appear, the events of history continue, and the facts and figures accumulate. If the 1930s was the decade of the blue-collar worker, then the just-completed 1960s was certainly that of the public employee. At the federal, state, and local levels of government, employees are in fact organizing, engaging in negotiations, and voicing grievances against their employers.

The American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, AFL-CIO, has 373,000 members. The American Federation of Government Employees, AFL-CIO, has 263,000. The two large postal unions, both affiliated with the AFL-CIO, have a combined membership of over 300,000 and have only recently demonstrated their militancy. In short, these workers are beginning to act just like all other employees.

Half in Education

And the figures of growth are almost staggering. Today, approximately one out of every six nonagricultural employees is on the public payroll. By 1975, by current growth predictions, 15 million people will work for some kind of government with the preponderance of growth continuing at the state and local levels. Between 1955 and 1965, state and local government employment increased by 65 percent while federal employment showed only a 13-percent gain. And, very important, about half of all state and local government employees work in education!

What shall be the relationship of all these millions of people with the sovereign, their employer? The answer at present is muddy and will probably not become completely clear for some time. It must be pointed out that sovereignty itself is not necessarily something abstractly fixed in a permanent place. Kings, as sovereigns, once ruled by divine right. No longer, at least in western countries.

The state itself, as seen by Hegel as an organic whole, a living, breathing, pulsating thins, is now under intensive scrutiny. Sovereignty, then, may no longer be considered as a “ghostly thing,” but as a process. Political Scientist Andrew Hacker has defined it as, “the interaction of specified individuals and institutions according to specified rules of procedure … The process of sovereignty, therefore, is more concerned with how laws are passed than with what they say.” Herewith, sovereignty becomes flexible, not fixed, and a real, not abstract, relationship.

The whole knotty issue was given significant clarification by President John F. Kennedy’s Executive Order 10988, of Jan. 17, 1962. The impetus of the order was to spell out conditions of recognition of employee organizations in the federal service.

Federal Policies

Prior to 1962, unions existed in federal employment, but nobody knew what rights and obligations they had. Executive Order 10988 filled that gap and also pointed out to unions and management at the state and local levels that regulatory machinery could be mutually helpful. It not only spelled out a clear-cut policy on the right of employees to organize, to have their organizations accorded official recognition, but it provided for consultation in the establishment of personnel policies and procedures and, under specified conditions, for negotiated agreements with agency management on working conditions.

Following the lead of President Kennedy, by mid-1969, 19 states had authorized by law some form of collective bargaining with state or municipal employees, or both. And 1,200,00 federal employees had exclusive representatives in some 1,800 units.

On Oct. 29, 1969, President Richard M. Nixon issued Executive Order 11491 superseding the Kennedy order. Under the Nixon order, a central authority consisting of the chairman of the Civil Service Commission, the Secretary of Labor, and officials from the President’s executive office, named the Federal Labor Relations Council, will administer the program. The Assistant Secretary of Labor for Labor-Management Relations is given additional power, such as authority to supervise the required secret-ballot elections and to determine the recognized unit. A Federal Service Impasse Panel is also established. It has authority to settle impasses in contract negotiation if other means fail. The exclusive representative will have the same negotiating rights as under the Kennedy order (importantly, matters determined by Congress are still excluded from the negotiations, e.g., pay, hours, leave). In addition, a new form of recognition has been created: national consultation rights. This designation will go to organizations that represent a “substantial” number of employees in an agency, but will not apply where an organization already holds exclusive recognition at the national level.

So, with an increasingly elaborate federal system of negotiation, and with 18 sates having laws requiring the public employer to bargain with at lease some state or local government employees, it would appear that the question of public employees’ rights to organize and bargain in their own interest would be settled. Not so. There are still many restrictions on their rights to do so. The question of the “public interest” is still open to interpretation between the two contestants and frequently results in the public agency being able to obtain a court injunction to make sure that its particular service is not interrupted.

The “Right” to Strike

The use of injunctions in public-employee strikes is increasingly viewed as an impediment to true collective bargaining. In Michigan, the state supreme court in 1968 (in a case involving Holland, Mich., teachers) upheld a refusal to enjoin a strike unless a clear and present danger to public health and safety was involved. A teacher strike, the court said, presented no such danger. Few other states, however, have moved as far as Michigan in this regard, although public opinion appears to be growing increasingly favorable.

It has been charged that enjoinment of a public-employee strike, such as a teacher strike, has the effect of forcing workers to stay on the job despite what may be intolerable and dangerous conditions. Teachers in Newark, N.J., for example, were driven to the last resort of striking early in 1970. The court issued an ex parte injunction, which means only one side presented its case to the judge, and the result was that 192 teachers were sentenced to jail terms and fines for not going back to work. The injunction included penalties against “aiding and abetting” the strikers, so that AFT President David Selden, who walked on a picket line, was sentenced to three months in jail for contempt of court.

Skirting the issue of the right of public employees to strike, just because it may be “explosive,” is comparable, some people think to avoiding other basic issues of fundamental importance to our society. Legal opinion in most of the United States views a strike against the government as a strike against the sovereignty of the nation, and this is said to be based on the old English common law, the foundation for much of our legal structure.

But while we are clinging to this old “monarchical” approach, the English, for example, are acting quite differently, and they say they are the ones who are following the common law most closely. In a letter to AFT President Selden recently, W.A.C. Kendall, president of the Association of Teachers in Technical Institutions, a union of vocations teachers in England and Wales, said: “I heard today, with considerable surprise, that you were in prison for pursuing what I would have thought were quite legitimate aims of a teachers trade union. That the leader of a teachers union can be so treated in the U.S.A. is a matter of considerable surprise to me. We have recently been involved in militant action and I would have been proud to go to prison had it been necessary but fortunately our law is more liberal.”

Historical Background

The first recorded strike occurred about 1170 B.C., when workers at the Necropolis in Thebes walked off their jobs because the government of Egypt had not paid them in two months. (Note, they were public employees.) And on April 13, 1970, the United Teachers of Los Angeles struck because of the long list of unresolved grievances involving the poor state of educational affairs in that city and state.

It would appear, then, that a dilemma is at hand. As stated earlier, the federal government prohibits its employees to strike – but they strike. Most states also prohibit they strike – the people strike. The dilemma has been phrased very well by Heisell and Hallihan in Questions and Answers on Public Employee Negotiation.

“Horn No. 1: Some public services are so vital to the immediate safety of the citizenry that a strike is unthinkable.

“Horn No. 2: Given sufficient stimulus, any group of employees, public or private, essential or nonessential, with or without the legal right to strike, will strike.”

It would appear obvious, then, that to legislate against strikes is only to provide punitive tools after the strike has taken place, tools that may or may not be usable. (Can one conceive of arresting 22,000 Los Angeles teachers?) More pertinent, it seems to us, would be adequate machinery to solve grievances so that the strike would become less necessary.

“More Conscientious”

It is noteworthy that public employees often seem more conscientious about professional standards than are their employers. Social workers have struck to have their caseloads reduced so that they can more effectively service their clients. Nurses and hospital attendants have struck to have more people employed in order to better care for their patients. And, certainly, one of the major demands of the Los Angeles teachers is the reduction of class size so that they can be better teachers.

It is equally important to note that much of the discomfort of public employees has to do with the whole growing “urban crisis.” More people in smaller spaces expect more and better services. Family patterns change, forcing public agencies to do what the extended family did, or did not do, before. New thrills, new “kicks,” seduce the proliferating urban young. (An official of the United Teachers of Los Angeles has asserted that in 92 percent of the secondary schools of that city drugs are a major problem.) And race relations continue to be extremely abrasive. Public employees, then, often see no way to change the “horse-and-buggy” structure of their employing agencies except to shock them with desperate action.

In any case, the teacher should keep in mind that all of his students in all his classes, 95 percent will shortly become somebody’s employees. And increasingly, the employer will be a public agency. We have prepared this teaching unit to help the teacher acquaint his class with what can be expected and what constitutes the problem areas.

Lesson 1

Preface: If there has been a recent teacher strike in your district, you may wish to discuss it as a general introduction to this unit. Or, you may want to talk about the postal strike or the air-traffic controllers’ work stoppage, or strikes by any group of public workers which have, in some way or another, had a direct effect on your students.

Aim: The teacher should acquaint his high-school students with the changing nature of the economy, from one geared to production and distribution of goods to one of increasing needs for public service. This should not be too difficult since studies reveal that today’s young people already sincerely want their life’s work to have social important.

Motivation: It seems to us that the greatest tool for motivation in this case would simply be to present as much concise and valid information as possible about the prospects for public service. Much material is available from public agencies and should be obtained by the teacher, condensed, and presented to his class. Perhaps a representative from the Civil Service Commission, the Department of Public Welfare, or a similar agency can be brought to the class for a presentation. If possible, the teacher should meet with the representative chosen to ascertain his ability in this matter. A poorly prepared or inarticulate spokesman can do great harm to the teacher’s class.

Lesson 2

Aim: The teacher is aware that much prejudice exists regarding the relationship between employer and employee, particularly organized employees. The aim of this lesson is to reduce this prejudice and dispel myths.

Motivation: Again, it is our conviction that reliable information, effectively presented, does much in this day of the “shuck and jive” to motivate young people to want to learn. If the teacher can find an effective representative of the American Federation of Government Employees or the American Federation of Teachers, he might profitably use that person to address his class.

Concepts to be developed:

1. American is a land where individual dignity goes hand in hand with collective strength. The individual, standing alone, is increasingly helpless in the face of complex, social stresses and needs.

2. The self-sufficient entrepreneur is rare. The overwhelming majority of Americans are somebody’s employees.

3. Historically, employees have organized and joined employee associations or labor unions for four reasons.

A. Economic: Employers, whether private or public, are interested in keeping costs down. Employees, facing ever-increasing costs of living as needs grow, have strength to bargain only if they can approach their employer with united effort.

B. Psychological: The long worker, perhaps performing routine tasks and far removed from authority, can find himself dehumanized – a little cog in a huge machine – and his personality damaged. Organization offers him protection from the martinet supervisor and it provides him with a sense of importance.

C. Social: The origin of the custom of calling fellow union members “brother” or “sister” is not mysterious. The gathering together of people of common interests is as old as history. It is comfortable to “belong” to something.

D. Political: Most social progress – land reform, public education, workmen’s compensation, social security – has been the result of political action. The union as a political organism is a fact of life. It is an instrument for achieving social change.

4. In whatever kind of economy, an adversary relationship will exist between employer and employee. Whatever employees gain, either economically or in prestige, surely must come directly or indirectly at the expense of the employer. There is nothing inherently “wrong” with this relationship and it need not be acrimonious or hateful. Indeed, within the framework of law, and with strong and honest contestants, the conflict of interest can be routinized to the advantage of both. It is generally when one of the contestants is overwhelmingly strong and the other hopelessly weak that, in desperation, violence occurs.

Lesson 3

Aim: In this lesson, the teacher much deal with the “nuts and bolts” of labor-management relations. He will define common terms, discuss methods used in resolving conflicts and analyze the law on the matter.

Motivation: At this stage, given the controversial nature of the subject, motivation and interest should be relatively high. A Socratic questioning approach might be used. (And, remember, the rhetorical question is not an academic crime!) Also, simulated bargaining might be used if the class generally is a bright one. Serious role-playing can be an excellent learning tool.

Current events: Daily newspapers are carrying stories of strikes by teachers and other public workers. You may wish to discuss the issues in the following strikes, their effects on the public, and the results for the workers. You can get information from general news publications, this and past issues of the American Teacher, and from public-employee unions (see Page A-6 for addresses).

a. San Francisco “general” strike

b. Newark teachers strike

c. Los Angeles teachers strike

d. Air traffic controllers’ action

e. Postal strikes

f. Nurses’ strikes (Michigan and elsewhere)

Explicit definitions of terms:

a. collective bargaining

b. bargaining unit

c. agency shop

d. union shop

e. exclusive recognition

f. consultation rights

g. union security

h. dues check-off

i. steward

j. fringe benefits

k. grievance procedures

l. “good faith”

m. mediation

n. arbitration

o. disciplinary action

p. “militancy”

q. injunction, ex parte injunction

r. The union

1. local

2. national

3. International

4. central labor council

s. public worker

t. government agency

u. civil service

v. profit-making corporations

w. Executive Orders 10988 and 11491

x. strike and lockout

y. scabs and strikebreakers

z. “health and safety”

Questions to be asked:

1. Why do employees always want “more?”

2. What is the difference between “cost of living” and “standard of living?”

3. What is the importance of President Kennedy’s Executive Order 10988 and of President Nixon’s Executive Order 11491?

4. Is there a difference between the way public and private employees are treated by law? Should statutes be used to deal with recognizing or not recognizing organizations of public employees?

5. Should the same statutes be used to cover all employees – teachers, policemen, firemen, sanitation workers, supervisors – or should different laws be used for different classifications of employees?

6. What guidelines, if any, should the law contain for the determination of bargaining units?

7. Should the law define “unfair practices” and prohibit them?

8. Should the legislature permit an “agency shop” agreement in public employment?

9. What terms and conditions of employment, if any, should be excluded from the bargaining process?

10. Are special provisions needed to protect civil-service rules and authority where they exist?

11. Should strikes be prohibited? For all workers? For all public workers, regardless of their work? If so, how? If not, should there be conditions imposed by law before a strike can be called by public workers?

12. Should compulsory arbitration be adopted in the public service as a means of resolving impasses in collective bargaining?

Summary: The teacher should attempt to tie up loose ends of the discussion, pointing out areas where there is no common agreement as well as where consensus seems possible. He should make certain to point out that the whole subject of public-worker organization is presently in an evolving state and that all conclusions should be tentative. He should, of course, take special care to sweep away as many cobwebs of mythology as possible. Let his students go forth with at least an open mind on the subject.

Suggestions for Class Activities

(These suggestions are general enough to be adapted to almost any grade level or group of students. Teachers should feel free to expand and build on them.)

Mock bargaining sessions: Some students can take the role of either a school board or other government agency, while other take the role of teachers, firemen, policemen, sanitation workers, etc. Both sides can privately draw up bargaining demands and counter offers and then participate in a series of mock bargaining sessions.

Debates: Classroom debates can be built around the pros and cons of public-worker strikes. One suggested issue: “Resolved: The public workers shall have the right to strike in cases which do not constitute a clear-and-present danger to public health and safety.”

Research: Students can check Dept. of Labor reports, etc., to discover the extent of public-employee work stoppages in the past decade, the number of employees involved, the attitudes of the public, etc.

Reports: Students can write compositions or reports on the use of injunctions in the private sector, on anti-injunction legislation, on public-employee strikes in other countries, etc.

Interviews: Students may wish to interview rank-and-file members and leaders of public-worker unions, judges who have invoked injunctions again public employees, city officials, and school officials, and then report on their interviews to the class.

Writing a contract: The teacher and the students may wish to write a collective-bargaining contract with each other (this has been done in some classrooms, see American Teacher, October, 1967). The contract may cover classroom conditions, individualized and independent study, grading policies, and other educational matters.

Picket-line support: Students should be given the opportunity to march on a picket line with public employees, if a strike occurs in your neighborhood and if students decide they want to support the strikers. They can make picket signs (a good sign has bold lettering suitable for TV-camera pickup and with no more than six or seven words). They can be taught picket-line discipline (lines are orderly, they’re single file or two abreast, they shouldn’t block entrances, and only the “picket captain” should issue statements).

Class discussions: These could include “meet-and-confer” laws as opposed to collective bargaining, the right of public workers to strike in other countries, the definition of “immediate danger to health and safety,” etc.

Writing project: What would you do if you were the leader of a teacher union and (a) the school board wouldn’t meet with your union; (b) you hadn’t received a raise in four years; and (c) class sizes had increased by five students each over the past three years.

Work Stoppages by Government Workers

Work Stoppages Involving Government Workers, 1966, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1967:

Total number of work stoppages nationwide in 1966 among governmental workers was greater than the four previous years combined. Of 142 stoppages in the U.S., none was reported by federal employees, nine involved state governments, and 133 were at local government levels:

54 were in public schools and libraries

36 were in sanitation services

19 were in administration and protection services

17 were in hospitals and other health services

About 105,000 out of 8.3 million state and local employees were involved. About two days were lost due to stoppages for every 10,000 days worked. (Corresponding ratio for private industry was 19 days in 1966.)

The major issues in 78 stoppages were salaries and related supplementary benefit. In 36 cases, organization and recognition disputes were central, while in 21 cases matters of administration were the principal issue.

Number of teacher strikes in the United States by years: 1880-1940, 20: 1940-1944, 17; 1945-1952, 73; 1953-1962, 20; 1963-65, 16; 1966, 33; 1967, 75; and 1968 (est.) 100 +.

Randy H. Hamilton, Exec. Dir., Institute for Local Self Government, reported:

Number of public employee strikes rose from 28 in 1962 to 42 in 1965 and to more than 150 in 1966.

Sources of Information

American Bar Association, “Committee Report on Public Employee Relations,” Special Report: Educators Negotiating Service, 1835 K St. N.W., Washington, D.C. 20006, Dec. 1, 1969

Anderson, Arvid (chairman, Office of Collective Bargaining, New York City), “Collective Bargaining and Public Employees,” Special Report: Educators Negotiating Service, Nov. 1, 1969.

Buder, Leonard, “To the Picket Line, Mr. Chips!” New York Times, Dec. 24, 1967.

“Employee-Management Relations in Public Service,” U.S. Department of Labor, Washington, D.C. 20210, Sept., 1967.

Goldberg, Joseph P., “Labor-Manager Relations Laws in Public Service,” Government Employee Relations Report, Bureau of National Affairs, 1231 25th St. N.W., Washington, D.C. 20037, June 17, 1968. D-1 to 8.

Neal, Richard, “Public Employees and Bargaining,” Special Report: Educators Negotiating Service, May 15, 1968.

Ross, Anne M., “Unions and the Right to Strike,” Monthly Labor Review, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington, D.C. 20212, March, 1969.

“The Right to Strike and the General Welfare,” Council Press, N.J., published for the National Council of the Churches of Christi, 475 Riverside Drive, New York, N.Y. 10027, 1967.

“The Worker’s Rights and the Public Weal,” Time magazine, March 1, 1968, pp. 34-35.

Public Personnel Association, 1313 E. 60th St., Chicago, Ill. 60637, Publications:

Collective Bargaining in the U.S. Federal Civil Service (1966), by W.B. Vosloo

Public Management at the Bargaining Table (1967), by K.O. Warner and M.L. Hennessy

Management-Employee Relations in the Public Service (1969), by Felix A. Nigro

Developments in Public Employee Relations (1965), edited by K.O. Warner

Collective Bargaining in the Public Service (1967), edited by K.O. Warner

Perspective in Public Employee Negotiations (1969), edited by Kenneth Ocheltree

Additional materials can be obtained from:

American Federation of Government Employees, AFL-CIO, 400 1st St. N.W.,

Washington, D.C. 2001

American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, AFL-CIO, 1155 15th

St. N. W., Washington, D.C. 20005

American Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO, 1012 14th St. N.W., Washington, D.C.

20005

Strikes in the Public Sector

(The following article is reprinted from “Labor Management Panel,” a publication of the Labor-Management School of the University of San Francisco (Vol. 20, No. 3, Jan.-Feb., 1970). Written by Eammon Barrett, editor, if presents a reasoned, dispassionate view of the issue of “strikes in the public sector” and is included in this teaching unit as background reading for the teacher.)

Strikes are becoming more frequent in the public sector despite laws enacted to outlaw them. So commonplace have they become that one wonders about the efficacy of laws outlawing them or the sanctions imposed to prevent them. This introduces the question as to whether or not public employees should be granted the “right” to strike.

Validity of Strikes

The right to strike is a natural right which is inherent in human nature. It does not come from the state but rather flows from the dignity and needs of the employees.

The individual laborer has a right to just conditions of employment, and to obtain these objectives, he has a right to join with his fellow workers for the purpose of collective bargaining. The right to strike follows as a corollary from these two rights. Generally speaking, if an objective is good, men may use any legitimate means to obtain this objective since there is no wrong involved in withholding one’s work from an employer, even when the act of withholding is concentrated. Actually, the right to withhold work, either as an individual or as a group, is what distinguishes free men from slaves, or distinguishes living under Communist rule from living under a democracy. Consequently, there is nothing immoral in a strike considered in and of itself.

However, what maybe good in itself or at least indifferent may become wrong by reason of the end sought or the circumstances involved. Accordingly, a certain criteria may be set down by which the morality of a strike may be determined in the concrete. In other words, while the right to strike is natural, it is not absolute.

Criteria For a Just Strike

The criteria for a just strike are:

1. A just cause;

2. A proportionate cause;

3. A right use of means;

4. A reasonable hope of success.

Just Cause

There must be a just reason for declaring a strike since work stoppages are always attended by some unhappy results, and unless there is a good reason for the stoppage the striker is responsible for whatever harm may follow. Low wages, overwork, or discrimination must be considered as just causes and hence justify what may be called a defensive strike.

The fact that an employer who is able to do so does not pay a living wage (or a wage which enables the employee to rear and educate his children at a level in keeping with his station in life or their economic well-being) constitutes a sufficient reason for a strike. If any form of coercion, either legal or moral, has been used to impose a certain wage on employees – one which is not in keeping with the requirements of their state – then the employees have a just cause for a strike.

However, because of the harm done by a strike to the employees and their families owing to loss of wages, and the sometimes extreme inconvenience caused the public as on the occasion of the New York transit strike, the right to strike should be involved sparingly and only after workers have made every reasonable attempt to settle their difference by such peaceful means as having recourse to mediation.

The government, as it has done under the Taft-Hartley Act, should device means of safeguarding the public interest, but not by legislating against a just strike when there is available to employees no other reasonable means of equitable redress, or, in the short-run, no other method of getting the dispute into the public forum so that the people can pass judgment on the issues.

As long as the ban on strikes continues to exist in the public service, two situations are likely to prevail.

The wages in the public sector generally will remain below wages for comparable jobs in the private sector, and working conditions will suffer.

Wages in the Public Sector

A few examples of the relationship between wages and working conditions for comparable employment in the public and private sectors are in order:

1. In 1961 the Department of Research and Retirement of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) carried out a study comparing wages in the public sector with wages for similar positions in the private sector. The result of the study was to make it at least arguable that public employees, without the right to strike, do not receive compensation commensurate with the value of their services, or equitable with that received by persons performing comparable work in the private sector. In comparing the average monthly earnings of “production workers in manufacturing” with those of public employees, excluding educational personnel, the study finds that the wages are lower than those of the private workers in 42 jurisdictions and higher in 7, of which California is one.

2. Throughout the State of California, there is no uniformity in police pay from one area to the next despite the fact that the risk to their lives every time they go on duty was increased for all policemen. For example, effective July, 1969, the new San Jose police pay scale includes $944 for an experienced patrolman, with incentive boosts up to $1,016 per month for men with advanced certificates from the State’s Peace Officers Standards and Training Commission. Meanwhile, the Vallejo Police after a strike on July 21, 1969, were granted a monthly pay increase from a previous $693 to $841.

3. The nurses’ strike in San Francisco in 1966 led to the establishment of a fact-finding commission which found salary inequities and raised pay substantially.

Many disputes are over conditions of employment.

The air traffic controllers were responsible for a nationwide traffic jam on June 18-20, 1969, when they participated in a “sick-call boycott” which is but another name for a strike. The purpose was to draw national attention to the “unsafe” working conditions and work loads, inadequate staff, and unsafe equipment which in turn were endangering the lives of air travelers. More than one news medium reported that in 1969 there were in excess of 300 “near-misses” in the air. As a result of the strike, the Transportation Secretary told the House Commerce Committee that he was setting up a panel of experts headed by John J. Carson, consultant to the Carnegie Foundation and the Urban Coalition, “to review air traffic controller personnel problems.” The controllers had been agitating for some time to have something done about the problems of air safety, and yet it took an illegal strike before anything was accomplished. Without the strike, the public would not have known about the possible risks they were running through air travel. It may require a couple of major air tragedies to bring before the public the inadequacy of equipment and unsafe working loads. And, after all, a strike, even an illegal though ethical one, with which many may disagree, is preferable to loss of life. (Some people feel that anti-strike statues may be unconstitutional.)

From Vallejo we can learn a lesson. The city council protested that it did not have sufficient money to pay increases demanded by the police and firemen and remained adamant on the point despite the fact that police were grossly underpaid relative to many other police forces locally. However, in the fact of a strike, albeit an illegal one, that was backed by many of the citizens, the money was found. Without the strike, all the talk and negotiations in the world would not have won them an increase.

The existence of wage discrepancies and the discrimination on conditions of employment, with both militating against just and equitable treatment for public employees, constitutes a just cause for strike action.

A Proportionate Cause

The second requisite for a just strike is a proportionate cause, that is, the benefits anticipated or hoped for from the strike must be sufficiently great to compensate for the inconveniences which it is likely to produce.

The wrongs which workers are bound to take into consideration before engaging in a work stoppage are not merely those which they themselves may suffer. They must also look to the welfare of others and may not inflict harm on their employers or on the general public to an extent far out of proportion to the advantages they may have set their goals, even if the demands are just and reasonable.

There is far too much emotionalism regarding the injury that can be suffered by the general public as a result of strikes in such areas as hospitals and fire departments. Even where there have been strikes in these two areas, the employees in question acted with a sense of responsibility and in no way endangered the lives or safety of others. During the June, 1969, Bay Area nurses’ strike, the nurses were at pains to minimize any danger to the communities involved. The California Nurses Association promised the hospitals help in handling emergency care. Again, during the mass resignations of nurses in the San Francisco area during 1966, essential services were attended to by nurses who refused to accept pay for those services. The nurses manned emergency stations and gave attention to patients who needed special care. There was a monetary loss to the hospitals, plus the inconvenience experienced by those patients who were obliged to delay entry into the hospital for elective surgery. Emergency and urgent cases were admitted. In both of these nurses’ strikes the benefits accruing to the nurses were sufficiently great to compensate for the supposed wrongs which the strike produced. For example, as a result of the June, 1969, strike the nurses who were paid $600 to $800 would get $50 more retroactive to January 1, $40 more in February, 1970; higher premium pay for night work; longer paid vacations and sick leaves; at least every fourth weekend off, and improvements in other benefits. However, it was the promise of a greater voice for nurses in staffing and nursing procedures that finally settled the strike. As long as there was no possibility of a strike, the hospital officials could and actually did remain adamant regarding the concessions made to nurses. Also, the 1966 strike forced the setting up a fact-finding panel whose members found, on weighing all the evidence, that the nurses were grossly underpaid and recommended a substantial raise in salary for them.

The next example is that of a strike by firemen in a city of over two million population in a country other than the United States. When the strike was first announced there was a deluge of publicity condemning the firemen for irresponsibly endangering the lives and property of the inhabitants. It was taken for granted the firemen would display a complete disregard for the safety of their fellow citizens. Actually, the strike took the form of a refusal to accept wages and a refusal to obey any orders within the confines of the fire station. Other than for those two factors it was duty as usual. They were at work each say and on the alert for fire alarms and always had their equipment ready for any emergency. They answered the usual fire calls, and in the course of fighting one such fire two firemen lost their lives. The tragedy put an end to the propaganda accusing the firemen of being selfish and irresponsible, and in addition it had the effect of convincing the public of the unfairness of the propaganda. The strike was settled immediately, with the firemen being granted the majority of their demands. Other than resorting to strike action, the only short-run remedy open to the firemen was to go on accepting wages lower than what to which they were entitled – either that, or lobby for paternalistic handouts from politicians concerned about their own reelection. Politicians do not wish to jeopardize their chances of reelection by either a tax increase or a change in the allocation of the tax monies. By accepting a wage lower than that to which they were entitled, the firemen could be said to be keeping incumbent politicians in office and thereby discriminating against political opponents who might be more just and less discriminatory.

Right Use of Means

The third requisite for a just strike is a right use of means. Strikes must confine themselves to what is permitted by the natural and civil law. It is difficult to define in detail what is permitted and what is forbidden in this matter. Certainly both physical violence and destruction are forbidden; on the other hand, peaceful picketing is allowed.

Reasonable Hope of Success

The fourth requisite for a just strike is a reasonable hope of success. In dealing with the strikes in the public sector, two important factors must be taken into consideration:

a) In the first place, strikes are outlawed in the public sector, and in some jurisdictions sanctions are attached to breaking the law. On the face of it, the existence of these laws and sanctions would make it appear that strikes in the public sector would have no reasonable hope for success and thus could not be justified.

b) However, the number of strikes has increased substantially in the last three years, thereby establishing a de facto right to strike.

Many of these strikes have been successful, as seen in the cases of the 1966 and 1968 nurses’ strikes in San Francisco, and the police and firemen’s strike in Vallejo. In addition, the general duty nurses at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami won a 15-percent wage increase as a result of strike action. These examples of success could be multiplied, and in light of this fact it is difficult, if not impossible, to state categorically that future public-employee strikes do not have a reasonable hope of success.

Books and Films

Thomas R. Brooks. Toil and Trouble. Delacorte, 1964. A well-written history which most students would enjoy.

Foster R. Dulles. Labor In America. Crowell, 1960.

Heisel and Hallihan. Questions and Answers on Public Employee Negotiation. Public Personnel Association, 1967.

Elias Lieberman. Unions before the Bar. Oxford Book, 1960.

Lieberman and Moskow. Collective Negotiations for Teachers. Rand McNally & Company, 1966.

Henry Pelling. American Labor. University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Joseph Rayback. History of American Labor. Macmillan, 1959.

Philip Taft. Organized Labor in American History. Harper, 1964.

Important Events in American Labor History, 1778-1964. U.S. Dept. of Labor, 1964.

Woodworth and Peterson. Collective Negotiations for Public and Professional Employees. Scott, Foresman, and Company, 1969.

AFL-CIO. Collective Bargaining, Democracy on the Job, pamphlet published by the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, Washington, D.C.

Twentieth Century Fund Task Force on Labor Disputes in Public Employment, Pickets at City Hall. New York: Twentieth Century Fund, 1970.

Leon Litwack, American Labor Movement, Prentice-Hall, 1962.

Raymond Ginger, Bending Cross, 1949.

Irving Bernstein. The Lean Years (1920-1933), Houghton.

Films

The Inheritance. A sweeping look at the 20th Century and the long, bitter struggle of workers against economic exploitation. 55 min. Available from AFT Order Dept., the AFL-CIO film library, and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

The Rise of Organized Labor. Good background on the evolution of unions and the labor movement. 20 minutes. Available from AFL-CIO film library.

Mother Is On Strike – This film shows police action in breaking up a picket line and scabs taking over jobs. 6 minutes. Available from International Ladies Garment Workers Union or AFL-CIO film library.

New York City Teachers Strike. An objective picture of this historic strike. 27 minutes. Available from United Federation of Teachers and AFT Order Dept.

Salt of the Earth. A feature-length film that portrays a long, desperate struggle between a group of New Mexico miners and the mine owners during the mid-1950s. It also shows the conflict between the male strikers and their wives who are seeking an equal voice in the union. Available from Brandon Films, New York and San Francisco.

Richmond Oil Strike. Portrays the 1969 strike of refinery workers in Richmond, Calif. Available from Newsreel, New York and San Francisco.

(The AFL-CIO Film Library is an excellent source of labor films. You can get a catalog for 25 cents by writing the AFL-CIO Pamphlet Division, 815 Sixteenth St. N.W., Washington, D.C. 20006, and asking for Publication 22.)

Questions and Answers About Teacher Strikes and Injunctions

The following questions and answers are taken from a new American Federation of Teachers publication, “Questions and Answers About Teacher Strikes and Unfair Injunctions,” and represents the AFT’s view of some of the issues covered in the preceding teaching unit. . Copies are available in pamphlet form from the AFT national office, 1012 14th St. N.W., Washington, D.C. 20005. The questions and answers were written by AFT President David Selden while he was serving time in prison during March and April, 1970, for his participating in the Newark, N.J. teachers’ strike.

Q: Are strikes by teachers illegal?

A: Yes and no. Many states have laws which prohibit strikes by public employees, including teachers, but even where there is no statute, courts will issue injunctions against striking by teachers if the school boards ask for them. Such injunctions also apply to “aiding and abetting” the strike by teachers or their agents or associates – the union itself, in other words.

Q: Are anti-strike and anti-picketing laws and court rulings unconstitutional?

A: Many legal authorities in the area of civil liberties believe that such laws and rules violate the 1st, 4th, 13th, and 14th Amendments to the United States Constitution, but it is highly doubtful that the Supreme Court would uphold an appeal by teachers at this time.

Q: Must teachers give up the right to strike, then?

A: Absolutely not. The power to strike is absolutely essential for good-faith collective bargaining. If teachers must keep right on working regardless of what the board of education or the superintendent does, there will be no incentive for good-faith bargaining.

Q: Do teachers have the moral right to strike even though the law or a court injunction may forbid it?

A: Yes. Injustice, such as forced labor or involuntary servitude, is morally wrong and refusal to comply with immoral laws or rules is morally justified. Philosophers such as Jefferson, Thoreau, Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the late Chief Justice Holmes have set for this concept many times.

Q: Then the AFT favors strikes by teachers?

A: Nobody “favors” strikes. The AFT favors negotiated contracts covering salaries, fringe benefits, teaching conditions and other matters of concern to teachers and to the children they teach. The AFT favors the right to strike as a guarantee of good-faith bargaining.

Q: Is it true that children lose when teachers strike?

A: Immediately, yes. In the long run, no. That is why AFT locals try to avoid strikes. But, on the other hand, children may suffer more from poor learning conditions, overcrowded classes, and disgruntled teachers than from a strike’s temporary interruption of their education. A long-run effect of the strike is improvement of learning and teaching conditions for teachers and children.

Q: How is the injunction used by school boards in a teacher strike?

A: School boards which fail to negotiate in good faith often force teachers to strike. Before teachers actually strike, the board of education can contact a judge who, knowing nothing about the cause of the strike, will issue an injunction without benefit of a hearing on the irrational principle that public employees cannot strike. Once in court, teachers are held in “contempt” for violating the court’s injunction and are very often fined and jailed after the strike has been settled to the satisfaction of both parties.

Q: How does the AFT propose to eliminate unfair use of injunctions in teacher-school board disputes?

A: By protest and political action. When a strike is necessary, teachers must be willing to risk the court-imposed penalties which may ensure until the law is changed. AFT President David Selden dramatized the anti-injunction protest by challenging a court order in Newark, New Jersey, and serving a 60-day sentence in the penitentiary. In the meantime, the AFT, in cooperation with the labor movement and other public and private organizations, is mounting a state-by-state campaign of political action.

Q: Can political action succeed in limited the unfair use of injunctions in teacher bargaining?

A: Yes – but it will not be easy. The support of all teachers, union and non-union, must be solicited. Also, direct help from local unions and central labor bodies and state labor bodies must be sought. Each state should have an “Anti-Injunction” or “Free Collective Bargaining” committee which should include teachers, other union representatives, and public members. The AI or FCB committee should coordinate efforts in each state.

Q: What do you mean by “political action?”

A: Candidates for the legislature should be supported only if they agree to vote for legislation which would limit the use of injunctions and the application of anti-strike laws to only those disputes which constitute a clear and present danger to public safety. In addition to action in primary and final elections of members of the legislature, a strong education and lobbying campaign should be carried on.

Q: Are limiting injunctions and anti-strike laws the only ways to win free collective bargaining?

A: No. Ultimately, legislation will be the most effective way. But in the meantime, determined challenge of the injunctive power and anti-strike laws will cause boards of education to be more cautious in the use of these anti-union devices, and courts will be encouraged to seek better ways to use their power. For instance, in Michigan, most courts now require a school board to show that it has made an effort to bargain in good faith (enter court with clean hands) before an injunction will be issued.

Q: How about federal legislation?

A: It’s a good trick if you can do it! There are many political and constitutional obstacles to overcome in order to secure such legislation. Education has been ruled a state function which can be regulated by federal law only when other rights are being denied by the state. CB for teachers may fall within this area, but at present it is a moot point at best. Most of our present problems center about unjust state laws and court actions. The political climate is more favorable to remedial action in some states than it is in others or in the Congress. Once we have been successful in some states, others will follow.

Q: What has been the experience in private industry? Weren’t injunctions once used to defeat strikes in the private sector?

A: Yes. Such injunctions were outlawed, in the federal courts, by the Norris-LaGuardia Act, passed in 1932. Before that, however, many states had enacted anti-injunction statutes of their own, and this action was secured at a time when the labor movement was much less powerful than now. The state laws paved the way for a federal prohibition.

Q: What’s wrong with the school board doing everything possible – including use of the injunction – to keep schools open? Isn’t this a part of its function?

A: Use of the coercive power of the state disrupts normal collective bargaining. The “bargain” agreed upon makes clear the terms and conditions under which teachers will give their labor. If the course, sheriff’s deputies, jails, and heavy fines are thrown in on the employer’s side, the “bargain” is apt to be unfair.

Q: Can teachers be fired for striking?

A: Yes. Firing for striking in private industry is prohibited as an unfair labor practice under most circumstance, but a striking teacher is technically guilty of “neglect of duty” and can be fired, despite tenure provisions. Thus, even if unfair injunctions were eliminated, teachers would still be at a disadvantage in bargaining compared with workers in the private sector. Of course, firing several hundred or several thousand teachers would be impractical as well as unjust, because it would be hard to replace so many skilled workers.

Q: Is there any substitute for the strike?

A: Ultimately, no. But there are steps which can be taken to reduce the likelihood of strikes and to minimize possible ill effects. Mediation during the final stages of bargaining helps avoid breakdowns and impasses over wording, for instance. Two-year contracts beginning with the first day of school in the fall reduce tension during the school year, although sometimes this arrangement is not practical due to peculiarities in budgeting schedules and other timetables beyond local control.

Q: How about arbitration?

A: Binding, impartial arbitration is essential as the last step in the grievances procedure in order to avoid work stoppages over interpretation of the contract. But submitting bargaining items to arbitration destroys collective bargaining. No one will negotiate if he knows that, in the end, an arbitrator will decide the issue. Both sides will want to go to the arbitrator with their optimum positions. Incidentally, this is really an academic question because very few school boards will accept arbitration on salaries, fringe benefits, and other budget items. Witness the Rhode Island experience where boards of education very often refuse to accept the terms of an arbitrator’s award.

Q: Does the AFT favor no-strike clauses in its contracts?

A: Most AFT locals willingly include no-strike clauses in their contracts – provided the contract also provides for binding arbitration in the grievance procedure.

Q: What would prevent teachers from abusing their power if they gain legal approval for striking?

A: The same restraints operate on teachers as apply to other groups of workers. Teachers risk loss of pay and fringe benefits and possible disciplinary action when they strike, just like other workers. Furthermore, teachers know that after a strike they will still have to bring their students through to academic success, and the longer the strike, the harder this will be. Hence, most teachers are eager to avoid long work stoppages for professional reasons.

Q: Isn’t a strike in public employment different from one in the private sector because of the lack of the profit motive and inability to pass the costs of the settlement on to the consumer?

A: This is only a superficial difference. The same “consumer money” must be used for the purchase of public labor, such as school teaching, as for private labor, such as auto manufacturing or the labor which makes TV sets. The question is how much of the total supply of money will be used for public projects, and how much will be used for other things; how much will be used to buy consumer items such as cars and TV sets and how much will be used for taxes (see writings of John Kenneth Galbraith).

Q: Should teachers wait until the law is changed so that teacher strikes are legally permissible for engaging in work stoppages?

A: No. If there is no agreement covering salaries, fringe benefits, working conditions, and other matters, teachers should not work. It will be difficult to induce legislators to vote for changes in present laws and rulings, because the “public” as employer has a selfish interest in the status quo. Teachers cannot wait for politicians to must up the courage to vote for what is right. If a strike is necessary, and all other methods to resolve the impasse have failed, teachers should have the courage of their convictions and they should push ahead.

Q: How do other countries treat teacher strikes?

A: Almost all democratic countries permit teacher strikes. The communist countries do not permit such freedom, of course. In Canada, federal employees may strike after exhausting preventive procedures. In Alberta, compulsory arbitration was tried for a few years but by agreement of both sides this system was abandoned in favor of the strike as the final means of settling disputes.

Q: You talk about “forced labor” as a result of injunctions. Isn’t this exaggeration?

A: No. Because of various seniority arrangements, such as step advancement on salary schedules, retirement credit, and tenure rights, teachers are trapped in their jobs. It is very difficult for them to move to another system. Hence, when they are prevented from exercising free collective bargaining, they are being forced to work under conditions not satisfactory to them.

Q: When teachers strike, they are not really “quitting.” Why don’t they resign if they don’t like their jobs?

A: Mass resignations have been declared illegal, too! Any concerted action to withhold their services can be enjoined just like an out-and-out strike.

Credits

The basic contents of this teaching unit – including of the overview and the suggestions for Lessons 1, 2, and 3 – were written at the AFT’s request by Will Scoggins, a noted labor historian who teaches at El Camino College in California. Mr. Scoggins received his B.A. degree from Baylor University in 1949 and his M.S. degree from the University of Wisconsin in 1951. In 1960, he attended the University of Oslo while on a Fulbright teaching grant in Norway. He has taught history and government in several high schools and colleges since 1951. In 1964 and 1965, he served on the staff of the Center for Labor Research and Education of the Institute of Industrial Relations at the University of California, Los Angeles, and spent several months inquiring into the instruction that high schools in Los Angeles County give students who will soon enter the world of work as someone’s employee. Out of that study came his book “Labor in Learning,” published by the University of California in 1966.

The teaching unit was critically reviewed by John A. Sessions of the AFL-CIO education department, and by several former classroom teachers now on the staff of the American Federation of Teachers national office in Washington, D.C. A number of staff members contributed supplementary information to the unit.

[Should Your Teacher Strike? Was converted from a .pdf copy of the insert supplied by Dan Glondner, AFT Archivist]

MARTIN LUTHER KING'S MEMPHIS SERMON, APRIL 3, 1968: Words to remember: "We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will get to the promised land. And I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about a thing. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord..." (the sermon Dr. King delivered in Memphis the night before he was murdered while supporting the union strike of Memphis sanitation workers). I'm delighted to see each of you here tonight in spite of storm warning. You reveal that you are determined to go on anyhow. Something is happening in Memphis, something is happening in our world.

As you know, if I were standing at the beginning of time, with the possibility of general and panoramic view of the whole human history up to now, and the Almighty said to me, "Martin Luther King, which age would you like to live in?" -- I would take my mental flight by Egypt through, or rather across the Red Sea, through the wilderness on toward the promised land. And in spite of its magnificence, I wouldn't stop there. I would move on by Greece, and take my mind to Mount Olympus. And I would see Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Euripides and Aristophanes assemble around the Parthenon as they discussed the great and eternal issues of reality.

But I wouldn't stop there. I would go on, even to the great hey day of the Roman Empire. And I would see developments around there, through various emperors and leaders. But I wouldn't stop there. I would even come up to the day of the Renaissance, and get a quick picture of all that the Renaissance did for the cultural and esthetic life of man. But I wouldn't stop there. I would even go by the way that the man for whom I'm named had his habitat. And would watch Martin Luther as he tacked his ninety-five theses on the door at the church in Wittenberg.

But I wouldn't stop there. I would come on up even to 1863, and watch a vacillating president by the name of Abraham Lincoln finally come to the conclusion that he had to sign the Emancipation Proclamation. But I wouldn't stop there. I would even come up to the early thirties, and see a man grappling with the problems of the bankruptcy of his nation. And come with an eloquent cry that we have nothing to fear but fear itself.

But I wouldn't stop there. Strangely enough, I would turn to the Almighty, and say, "If you allow me to live just a few years in the second half of the twentieth century, I will be happy." Now that's a strange statement to make, because the world is all messed up. The nation is sick. Trouble is in the land. Confusion all around. That's a strange statement. But I know, somehow, that only when it is dark enough, can you see the stars. And I see God working in this period of the twentieth century in a way that men, in some strange way, are responding -- something is happening in our world. The masses of people are rising up. And wherever they are assembled today, whether they are in Johannesburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Accra, Ghana; New York City; Atlanta, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; or Memphis, Tennessee -- the cry is always the same -- "We want to be free."

And another reason that I'm happy to live in this period is that we have been forced to a point where we're going to have to grapple with the problems that men have been trying to grapple with through history, but the demands didn't force them to do it. Survival demands that we grapple with them. Men, for years now, have been talking about war and peace. But now, no longer can they just talk about it. It is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence in this world; it's nonviolence or nonexistence.

That is where we are today. And also in the human rights revolution, if something isn't done, and in a hurry, to bring the colored peoples of the world out of their long years of poverty, their long years of hurt and neglect, the whole world is doomed. Now, (I'm just happy that God has allowed me to live in this period, to see what is unfolding. And I'm happy that he's allowed me to be in Memphis . . . .