'...More people are coming to see this conflict as an issue of popular democracy versus bankers’ rule...' Analysis in 1980 showed how corporations in Chicago refused to pay taxes, then created the 'Shock Doctrine' effect that forced the School Finance Authority on CPS for nearly 30 years

As the Chicago Teachers Union moves towards its first city-wide all membership meeting in 32 years, a bit of a history lesson might be in order, and one of the best places to find that lesson is in back issues of Substance (as well as in some materials from the Chicago Union Teacher). In November 1979, the financial rating agencies (Moody's and Standard and Poors; there was no Fitch then) announced that the Chicago Board of Education was having its rating lowered because of financial problems. Within six weeks, CPS workers went home for Christmas 1979 without being paid. Teachers and other workers went back to work in January 1980, while city, state and school leaders worked on how to finance the supposed problems of CPS. (If this sounds like Europe today, well...).

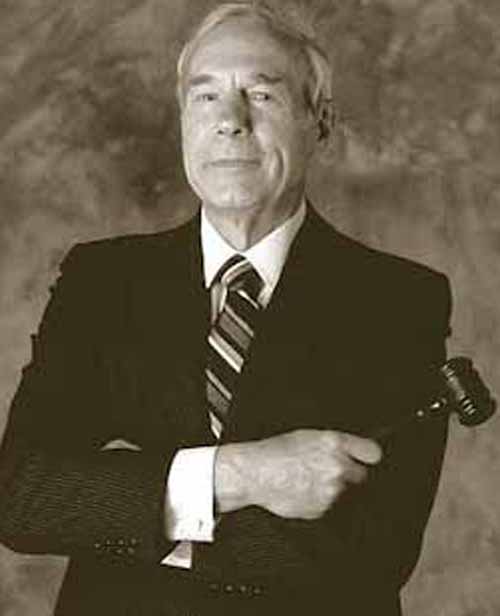

Chicago venture capitalist Martin Koldyke (above, speaking at Sherman Elementary School on January 31, 2008) served as the last chairman of the Chicago School Finance Authority. The SFA was transmongrified into the "Chicago School Reform Authority" (with Koldyke still as chairman) following the passage of the Amendatory Act of 1995, which gave Chicago's mayor (then Richard M. Daley, above right) dictatorial control over the Chicago Public Schools. Under the SFA laws, which began in 1980, Koldyke and his predecessor, the controversial Jerome Van Gorkom, had complete control over the Board of Education's budget, following the Shock Doctrine "bankruptcy" of CPS in 1979 - 80 (a reality created by the refusal of Chicago corporations to pay a corporate tax). Koldyke refused to approve the Chicago Public Schools budget in August 1994, forcing the schools to delay opening (a fact which was a lockout but which was reported by some prominent local reporters and pundits as a strike). Koldyke's reason for locking out CPS in 1994 was that although the 1994 - 1995 budget was balanced, the next two years might not have balanced. At the time, the SFA had complete power to approve or not approve all CPS spending, and could require a "balanced budget" for three full years ahead. Once the Amendatory Act took away much of the bargaining rights of Chicago teachers and made the conservative Daley head of the school system, the financial power of the SFA was lifted and Koldyke became the city's "Chief Reform Authority" head. Substance photo by George N. Schmidt.While the official version of reality was being reported in the Sun-Times, Tribune, and the other newspapers (as well as on TV and radio), some Chicago substitute teachers along with reporter David Moberg, then writing for the Reader, discovered that one of the reasons the Chicago Board of Education didn't have as much money as it was supposed to was that the city's biggest corporations had been refusing to pay a tax called the "Corporate Personal Property Tax." The result was the big hole in the CPS budget that the Wall Street rating agencies claimed was the problem.

Chicago venture capitalist Martin Koldyke (above, speaking at Sherman Elementary School on January 31, 2008) served as the last chairman of the Chicago School Finance Authority. The SFA was transmongrified into the "Chicago School Reform Authority" (with Koldyke still as chairman) following the passage of the Amendatory Act of 1995, which gave Chicago's mayor (then Richard M. Daley, above right) dictatorial control over the Chicago Public Schools. Under the SFA laws, which began in 1980, Koldyke and his predecessor, the controversial Jerome Van Gorkom, had complete control over the Board of Education's budget, following the Shock Doctrine "bankruptcy" of CPS in 1979 - 80 (a reality created by the refusal of Chicago corporations to pay a corporate tax). Koldyke refused to approve the Chicago Public Schools budget in August 1994, forcing the schools to delay opening (a fact which was a lockout but which was reported by some prominent local reporters and pundits as a strike). Koldyke's reason for locking out CPS in 1994 was that although the 1994 - 1995 budget was balanced, the next two years might not have balanced. At the time, the SFA had complete power to approve or not approve all CPS spending, and could require a "balanced budget" for three full years ahead. Once the Amendatory Act took away much of the bargaining rights of Chicago teachers and made the conservative Daley head of the school system, the financial power of the SFA was lifted and Koldyke became the city's "Chief Reform Authority" head. Substance photo by George N. Schmidt.While the official version of reality was being reported in the Sun-Times, Tribune, and the other newspapers (as well as on TV and radio), some Chicago substitute teachers along with reporter David Moberg, then writing for the Reader, discovered that one of the reasons the Chicago Board of Education didn't have as much money as it was supposed to was that the city's biggest corporations had been refusing to pay a tax called the "Corporate Personal Property Tax." The result was the big hole in the CPS budget that the Wall Street rating agencies claimed was the problem.

The solution, of course, would have been to force those corporations to pay that tax, but that was not the solution Chicago's ruling class wanted. What they wanted was to get rid of an Illinois "Usury" cap (which barred the banks from lending money to municipal bodies at rates above a modest amount) and put the Board of Education on an austerity budget. Ultimately, what happened was that the Chicago Board of Education had its own financial affairs taken away from it, and put under the control of the "Chicago School Finance Authority." The SFA borrowed more than a half billion dollars (at unprecedented interest rates) and became dictator over Chicago's public schools, ultimately for 16 years (until the ruling class replaced much of the SFA's power with the new Amendatory Act, which gave the power over CPS to the mayor in 1995 and loosened the strings of the SFA).

During the "crisis" of 1980, Substance and Substitutes United for Better Schools (S.U.B.S.), which published Substance at that time, published a pamphlet with an introduction by George Schmidt. The pamphlet, reprinting a Reader story by David Moberg, exposed the financial forces that were really behind the school system's financial "crisis." But like the "Manufactures Crises" of later years, instead of solving the problems of CPS in a way the helped the teachers and children, Chicago's rulers put the schools in a financial straight jacket. Below is a reprint of the pamphlet originally published by Substance, so that teachers and other school workers in 2012 can see some of the ways in which, especially in corporate Chicago, history repeats itself.

Introducing the Three Bs. (What’s Behind the School “Crisis”?). Bankers, Businessmen, Bankruptcy, By David Moberg. Introduction 1980 by George N. Schmidt. First published as a pamphlet by S.U.B.S. and Substance in February 1980 by Substitutes United for Better Schools, Chicago.

(This article reprinted with permission from the February 1, 1980 issue of the Chicago READER. © 1980 Chicago READER, Inc. A shorter version of this article originally appeared in IN THESE TIMES)

Introduction

Substitutes United for Better Schools (S.U.B.S.) is reprinting the following article “Bankers, Businessmen, and Bankruptcy” by David Moberg, because we believe that every striking teacher and every parent and student should know this information now.

By February 5 [1980], the Chicago Teachers Union was before the court, facing contempt of court charges for striking. Its leaders may face jail, it’s members fined.

Meanwhile, both major daily newspapers, the TRIBUNE and the SUN TIMES, were attacking the teachers’ strike as “unreasonable”. The strike is unique in Chicago history, because it is the first time that union teachers have struck simply to preserve education programs. No striking teacher will get a penny more for winning this strike.

But the strike is the most effective in the history of the Chicago public schools. Only the president of the Board of Education and the Interim General Superintendent of Schools seem to think the schools are open – or that they were open from January 28 through February 1. On February 4, Interim Superintendent of Schools Dr. Angeline Caruso said that the striking teachers “didn’t know the facts.” Both regular teachers and the city’s more than 2,000 substitute teachers know most of the facts all too well. That’s why we’re out.

But the media seem to think it can distort the facts and join with the courts and the banks to force us back to work. On February 5, the Chicago SUN TIMES criticized CTU president Robert Healey in its lead editorial:

"Robert Healey, president of the Chicago Teachers union, sabotaged his cause with his nonsense about bankers plotting the school system’s financial breakdown. Any teacher who fell for that simplification needs some courses in remedial mathematics..." (SUN TIMES, 2/5/80, page 37).

In our opinion, it is the SUN TIMES, not Mr. Healey, who is wrong in this case.

Where was the city’s largest circulation daily newspaper while Dr. Joseph Hannon, the former superintendent of schools, was juggling the books? Like most of the media, they were in the cheerleading section, flattering Dr. Hannon for his charm.

Jerome Van Gorkom, who died in 1998, served for a decade as chairman of the Chicago School Finance Authority, which forced austerity on Chicago's public schools following a "bankruptcy" caused by a corporate tax strike. During the first three years of the SFA's power to approved the city's public schools budget, CPS was forced to reduce its workers by a total of 8,000 people (between January 1980 and October 1982), forcing the highest class sizes in Illinois on the city's public schools and prompting four major strikes led by the Chicago Teachers Union as successive boards of education attempted to squeeze additional cuts from the teachers and those who worked in the schools while the school system was forced to repay billions of dollars in bond debt. It is striking that the SUN TIMES could criticize Mr. Healey while being so uncritical of its own role – or so ignorant of the information contained in the following article. They certainly have greater resources than the Chicago Teachers Union or the Chicago READER, the weekly newspaper which published the article. Why didn’t they dig as deep as Mr. Moberg did?

Jerome Van Gorkom, who died in 1998, served for a decade as chairman of the Chicago School Finance Authority, which forced austerity on Chicago's public schools following a "bankruptcy" caused by a corporate tax strike. During the first three years of the SFA's power to approved the city's public schools budget, CPS was forced to reduce its workers by a total of 8,000 people (between January 1980 and October 1982), forcing the highest class sizes in Illinois on the city's public schools and prompting four major strikes led by the Chicago Teachers Union as successive boards of education attempted to squeeze additional cuts from the teachers and those who worked in the schools while the school system was forced to repay billions of dollars in bond debt. It is striking that the SUN TIMES could criticize Mr. Healey while being so uncritical of its own role – or so ignorant of the information contained in the following article. They certainly have greater resources than the Chicago Teachers Union or the Chicago READER, the weekly newspaper which published the article. Why didn’t they dig as deep as Mr. Moberg did?

In fact, the SUN TIMES has been routinely made aware of the Board of Education’s chicanery and has routinely chosen to ignore it. On March 28, 1979, the Board of Education sold the land at the corner of Madison and Dearborn Streets to First Federal Savings of Chicago for what has since been called the “bargain basement” price of $7 million.

We at S.U.B.S. think that every teacher, students, and parent in this city should read the following article before they allow our schools to me mortgaged to the nation’s largest banks for the next thirty years.

We also think that anyone who criticizes Mr. Healey for his opinions about the banks should read this information first.

In our opinion, Mr. Healey is right.

In our opinion, it is the SUN TIMES that needs a course in remedial investigative journalism, not the teachers a course in remedial math.

--George N. Schmidt, President,

S.U.B.S.

Member, Chicago Teachers Union

February 5, 1980

The following article is reprinted with permission from the Chicago READER, Friday, February 1, 1980. c 1980 Chicago READER, Inc. and by permission of the author. The 25¢ donation requested for this reprint is solely for the purpose of paying the cost of the materials. If you need extra copies, please call Substitutes United for Better Schools at 341-0977.

Bankers, Businessmen, & Bankruptcy

By David Moberg

Woody Guthrie once warned that some thieves would rob you with a six-gun, others with a fountain pen. A similar moral emerges from the great Chicago schools controversy that we’ve been following for the last couple of months: some coups d’état are made with tanks, others with financial bonds and certificates.

As a result of a “bankers’ strike” – a refusal to loan money – precipitated by the downgrading of the school district’s bonds, Governor Thompson, Mayor Byrne, and the other architects of the precarious plan to “save” the schools have transferred the ultimate authority over them to a small group of businessmen, bankers, and lawyers.

The power of the “business community” already dominates the school debate, forcing drastic cuts and pressuring for renegotiation of contracts with school district employers. But that power will be applied far more directly in years to come, when the new School Finance Authority takes full control of the bail-out program. Jerome Van Gorkom, chairman of the authority, made that much clear last week, when he showed his pique at the school board’s hesitation to cut programs. Next year, he indicated there will be no shilly-shallying around.

It is ironic that direct capitalist control of the schools, only slightly tempered by the political system, should be offered as the solution to the school crisis, in the manner that the Emergency Financial Control Board was instituted several years ago to “solve” New York City’s ailments. Chicago’s public education system has been brought to the current impasses by years of corporate (and small business) exploitation, combined with the Machine politics and racial manipulation that have made Chicago a “city that works” – in the narrow and very short-term interest of business.

In the controversy that has swirled about the schools, the angry finger of accusation has been pointed at Jane Byrne, at Joseph Hannon, at the late Mayor Daley, at the school board, at the teachers and their unions, at Governor Thompson, and even at newspaper reporters, for not having caught the problem earlier. There’s some justice in criticizing all of the above for their recent and past sins. But there is even more reason, I believe, to single out business and bankers, because their contribution to the school system’s problems is far greater than that of any of the other malefactors. It also forms the context within which all the other irresponsible actions have been taken.

Indirectly, the business and banking interests have long had great influence over the schools and profited handsomely from their clout. The influence has as often been indirect as direct, but it has been powerful nonetheless. The damage to the schools has come in the form of lost revenues, extra capital costs, and the waste that has been an essential part of Chicago’s Machine politics.

From 1970, for example, the collection of personal property taxes in Cook County dropped from an already low rate of 63 percent to 40 percent in 1978. The failure to collect these taxes cost Chicago schools about $75 million in 1977 along, and an estimated $114 million in 1978. More revenue – about $40 million a year in state aid that is linked to local assessments and collections – was also lost.

To keep these figures in perspective, remember that the cuts being ordered for the schools this year would total around $60 million. Consultants to the school board have estimated that before next September, the school system must raise $459 million through the sale of long-term bonds to get back on a sound financial footing.

If businesses had been paying their taxes over the years, there might be no financial crisis in the schools. If the back taxes they owe were collected in full, there would be no need for wholesale cutbacks.

The rate of corporate default on taxes has climbed over the past decade in part because the 1970 state constitution mandated a replacement for the corporate personal property tax. That replacement was not put into law until 1979, and in the interim the tax was a lame-duck levy that many businesses chose to avoid. Their refusal to pay has a double effect for revenues from the new replacement tax are distributed according to how much of the old tax was collected (not assessed) in each county. In some downstate counties, the collections of corporate personal property tax were around 95 percent of assessments. The new tax scheme thus perpetuates Chicago’s short shrift; the city and its schools will continue to get less out of businesses than they deserve.

You can go down to the County Building and get a concrete feeling for the extent of the problem. Take a look at the personal property tax warrant books and run down the list of businesses, big and small. Look at the tax assessments. Then look at all the blanks in the column for taxes paid. As you’re flipping through just a few pages of one book, these figures leap out: Fleet Management Publishing Corporation, $23,000 assessed and nothing paid; Great Lakes Coin, $83,000 assessed, nothing paid; ILC Peripherals (a leasing company), $220,000 assessed, nothing paid. Blank spaces appear next to all these names, too: Trans Pac Leasing, $112,000; Comma Corporation, $43,000; Little Corporal Restaurant, $12,000; Loop Book Store, $22,000; Advance Theatrical, $48,000; Carteaux, Inc., $58,000. That’s just for 1977. And that’s just from a few pages of one ledger book chosen at random. The list goes on and on, often with even larger figures. As of last November, 5,422 firms in Cook County had failed to pay at least $10,000 in corporate personal property taxes.

But you can also go through the book and find business names, followed by a large tax bill, followed by a miniscule take payment. In many of these cases, the state’s attorney filed a lawsuit and negotiated settlements with the businesses for a tiny fraction of the bill. They know it can be done easily.

Here are a few figures, and a few familiar names. Burns Security paid $1,191 out of $25,983 owed; DDCC Leasing Corporation paid $2,826 out of $93,499; Standard Manifold paid $485 out of $22,621; Budget Rent-A-Car paid $444 out of $5,000; EWB Fur Company paid $26 out of $23,143; All Work Inc. paid $258 out of $41,090; Blackstone School of Law paid $25 out of $114,465; Leo Burnett Company (the advertising firm) paid $2,048 out of $10,883; Marsteller Corporation paid $1,000 out of $222,032; Jenner & Block (the law firm) paid $487 out of $17,610; and very famous, very rich IBM paid $3,991,526, though their bill was for $7,920,018 – meaning they avoided paying a not-so-insignificant $3,928,492. Again, that’s for 1977 corporate personal property tax.

Some of the biggest tax savings in recent years have been made by IBM, Drexel Ice Cream, Herlihy Mid-Continent Company, Marion Business College, Joseph T. Ryerson & Son, Ace Foundry, Exchange National Bank, Aetna Insurance, Wieboldt Stores, Polk Brothers, D.A. Matot Inc., Arco Polymers, Sunbeam Corporation, and Illinois Bell Telephone, which is fighting millions in taxes in court.

Any effort to save the schools might start with collecting the full assessed amounts from all of these companies. Interested citizens might want to call on them to find out what they have collectively scuttled the schools (and other city services as well).

The first protest might start with the Chicago School Finance Authority, the new masters of the school system. These are the people now responsible for the fate of education in Chicago and for commanding vast cuts in order to make the school bonds marketable to banks. One of the five members of that board is Jay A. Pritzker, described by the Tribune as “a member of one of Chicago’s most powerful financial families, … a philanthropist, partner in the law firm of Pritzker & Pritzker, and chairman of Hyatt Corporation, one of the nation’s largest hotel and hospital chains.” (Take note that one of the candidates for managing Cook County Hospital, which was run into the ground in part by the same corporate skullduggery that has drained the schools, is Hyatt Corporation.)

What has philanthropist Pritzker done for the schools lately? Looking over the same corporate personal property tax records for 1977, we find that the owners of the Hyatt Regency in Chicago were assessed $99,054.54 in corporate personal property tax in 1977. How much did they pay? $19,548.17. Perhaps philanthropist Pritzker would like to generously give the remaining $79,516.37 to the county. That might make it possible for a few inner-city black kids to remain in a special program that will allow them to finish high school.

There are also a least three other properties with unpaid 1977 taxes listed by the county assessor as belonging to Hyatt Corporation – the Hyatt Patisserie at 233 N. Michigan as paid nothing of $1,331.52 owed; a Hyatt property at 800 N. Michigan has paid only $2,712.24 out of $8,877.88 owed; another property at 39 S. LaSalle has paid $250.41 out of $500.81.

The money is important, but there is something far more grave involved. Here is a man who is extremely wealthy and the head of a giant corporation that has succeeded in avoiding thousands of dollars in taxes. How is he rewards for his part in the school crisis? He’s put in charge of it, with virtually no way for democratic control to check his power. Beyond this personal bitter irony, his appointment is symbolic of the entire Finance Authority – putting in charge of the remaining chickens the foxes that have been feasting on poultry for years.

Businesses have victimized the schools in other ways, besides not paying their personal property taxes. Many businesses are greatly under-assessed. During the early 70s, the Citizens Action Program unearthed repeated instances of under-assessment, involving major office buildings and such companies as U.S. Steel, but nobody has had the resources or chosen to use them in recent years to uncover more examples. However, the Tribune’s Ed McManus did report that reductions in real estate assessments of prime corporate property totaling $1.1 billion were routinely granted during a seven-year period. William Singer’s 1975 study of Chicago schools concluded that they were then losing at least $50 million a year because of under-assessments.

Assessments of property values for taxes have become skewed over the past decade in a way that deprives the schools and other public agencies of legitimate revenue. The assessed value of property has fallen from over 42 percent of the fair market value in 1970 to under 28 percent in 1977. Much of that has meant breaks for businesses of all sizes, but some of it has also given homeowners a tax break – a subject that I’ll return to later.

Some of the business tax avoidance has simply reflected the old cronyism and corruption that have been City Hall staples for years. But much of it has resulted from direct or indirect economic blackmail, a blight suffered by most cities, especially the older ones.

Last week, for example, Hilton Hotels Corporation’s James Sheerin testified that his firm wouldn’t build its new north Loop hotel if it didn’t get a tax break that would cut real estate taxes on the site by over half for 13 years. The break amounts to $70 million, or roughly $30 million less for the school. Do the Hilton executives need that break in order to operate the hotel profitably, or do they perhaps think they have the city over a barrel? After all, the Marriot on Michigan Avenue didn’t need a special incentive package, nor did the new Hyatt Regency at Illinois Center. What’s Hilton going to do if they don’t get their tax break in Chicago – build in Peoria?

The Cook County Board of Commissioners is considering legislation now that would extend tax breaks to other developers in the city and suburbs. Numerous studies, recently well summarized in Robert Goodman’s The Last Entrepreneurs: America’s Regional Wars for Jobs and Dollars, have demonstrated the long-term bankruptcy of such a plan.

There obviously is a serious problem in the city’s declining tax base and steady loss of jobs, especially in manufacturing. Despite the low rate of taxation, the special tax deals, and the tolerance of tax defaults, businesses have been fleeing Chicago and moving to the suburbs, the sun belt, and elsewhere. In many cases, these businesses have made their start in the city, accumulated their capital as they grew – taking advantage of the resources of the city and its people – then moved on, leaving behind an empty shell of a building, longer unemployment lines, and higher costs to the city government. The treat of business leaving has been an unofficial “vote” carrying considerable weight in every government council. Yet even when business wins concessions from the public, it makes no long-term, binding commitment in exchange to stay in the city and keep up employment. Tax incentives are one-sided deals at the taxpayer-citizen’s expense.

Under legislation now being considered at the state level, large companies that are planning to shut down their operations would be required to give advance notice, severance pay to employees, and a contribution to a community redevelopment fund. If that legislation had been on the books during the past decade, many businesses could have been saved – in a few cases by converting them to worker-owned enterprises – and community funds could have built up enterprises to replace both the jobs and revenues lost. As a result, the schools would have prospered a little, businesses a little less.

Rather than cut taxes and ultimately cut services in the vain hope of luring more business, the city should instead work to improve the schools, the services, and the quality of life for everyone – which means putting jobs, housing, and services for the poor neighborhoods at the top of the list. Then business will be attracted, stimulated, and retained on the basis of the city’s positive qualities. Without the capacity to plan productive enterprises directly, the city can only make a wager in any case; it’s better to put the money on an improved Chicago even if it means higher taxes for the rich and businesses, than on a cut-rate, run-down city that nobody would want. There are still other ways that businesses have profited at the expense of the schools. In the past few weeks, there have been numerous stories about the school board leasing or selling prime city property, much of in the Loop, for far below market value. The 1975 Singer report estimated a loss of $5 million annually from these low rents. George Schmidt, an assiduous researcher of the school system who is present of Substitutes United for Better Schools (SUBS), puts the loss at more like $100 million annually.

Banks and wealthy individuals who buy municipal bonds (virtually all held by people in the upper 1 percent income bracket) have made hundreds of millions of dollars in interest over the past decade on the short-term bonds and certificates that are issued to cover expenses until taxes or aid arrives. The pattern of borrowing, which obviously adds heavily to the financial burden of the schools, is exacerbated by the slowness with which taxes are paid. For example, although banks and savings and loan associations collect real estate taxes monthly on their mortgages, they pay the taxes only twice a year. So banks accumulate interest not only on the bonds sold in anticipation of the taxes but also on the taxes themselves, which they collect well in advance. Debt service as a fraction of the school budget has risen over 50 percent in the past decade to nearly one-tenth of the total.

One result of the current crisis is that the cost of debt will go even higher. The downgraded bonds carry higher interest rates. But even the $50 million loan package to the schools from the city, which was not secured by the school board’s shaky reputation, carried the extremely high interest rate of 10.675 percent, well above the current benchmark rate of 7.32 percent. For an investor in the 50 percent tax bracket, the typical buyer of these tax-free bonds, that means an effective return of 21.35 percent – not bad for even General Motors or Exxon, and actually even more profitable than those stocks for some higher bracket investors.

Beyond the relatively direct ways in which businesses, banks, and the wealth have robbed the schools and pocketed hefty sums, there is another, less direct way in which business interests have contributed to the school crisis. These costs stem from the Machine rule of Chicago politics – something that was juggled a bit but not seriously transformed with Jane Byrne’s election.

Mayor Daley put together the Machine not only with patronage but also with the loyalty of most of the city’s trade unions and with the support – including large financial contributions – of most of the city’s business interests. That Machine has played to certain interests of some white neighborhoods, run a fairly tight “plantation” system in the black wards, and maintained segregation and racial tension in a system that ultimately served primarily downtown businesses at the expense of the neighborhoods, especially the black ones.

What are some of the costs to the schools connected with this business-oriented Machine rule? One extra burden that we all are now at least passingly familiar with is the very high administrative cost. Administration expenses as a portion of the budget doubled during the past decade. Roughly one-fourth of suburban school district employees are non-teachers, according to Pierre DeVise’s recent tabulation, compared with one-third in Chicago. In 1975 Chicago had 30 percent more principals and assistant principals than the national average. Much of that padding has been modified Machine patronage: for example, Milton Rakove reports that 25 percent of the school systems’ district superintendents are Irish. They city is only 4 percent Irish (less in the schools), but it’s run b a Machine that wears the green as well as pockets it.

“The biggest single cost has been maintenance of segregation,” SUBS president Schmidt maintains. Whether or not it’s the biggest, the cost – even in narrow financial terms, not to mention the more serious social costs – is substantial. With surplus space for 59,000 students this year, the school board is nevertheless building six new schools at a cost, including interest, that Schmidt puts at nearly $60 million. All these schools are strategically located near the borders of racially changing neighborhoods. Their effect – or their purpose – will be to concentrate blacks and whites in separate schools instead of dispersing blacks to underused schools in white neighborhoods and furthering the legally mandated desegregation of the schools. Since 1960, Schmidt estimates, nearly half of the total school construction cost, or over $400 million, has been spent to perpetuate segregated schools. If the schools were desegregated, they would also receive more money, through various state and federal programs designed to implement and encourage desegregation. Schmidt estimates the amount at $90 million a year, although others cite lower sums:

A cornerstone of Machine political strategy has been a form of institutional segregation, designed to keep whites from fleeing the city. Working-class whites are of course the strong political base of the Machine, and it has also been calculated that business prefers a whiter city. The schools have been a mainstay of this tactic. A report issued by the federal Department of Health, Education, and Welfare last year again demonstrated how the Board of Education consciously worsened school segregation beyond what would have been produced by the already segregated housing marking alone.

Former schools superintendent Joseph Hannon consolidated his political support by agilely delaying action on school desegregation. The resultant shield from criticism, coupled with his own penchant for arrogant secrecy, helped him over the years to camouflage the deficits and shady juggling of funds. Because some storm warnings of fiscal problems were occasionally issued by groups like the Civic Federation, it is difficult to believe that the bankers and accountants were unaware of the fiscal difficulties developing over the years. It is also significant and not pure coincidence that the business leaders of the city have not spoken out for desegregation – not even though Chicago United, a group drawn from the business elite that has at last recognized the need for better education of students (of whom they described themselves as a principal “user”).

School segregation has also been linked to a housing and residential property-tax strategy that has backfired, also contributing to the financial downfall of the school system.

The property tax rate has been kept fairly constant throughout this decade. (The rate is below the median for large cities.) This has been especially important for winning the loyalties of white homeowners, many of whom no longer have children in the public schools, and a very large number of whom send their children to Catholic schools. It has meant that property taxes have not bee called on to do all they might in support of schools. (At the same time, it seems that black property-tax payers have been called on to contribute more than whites. Professor Arthur Lyons, of the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle, has discovered that blacks were assessed unfair property taxes. The recent rebuttal from the assessor’s office, he says, works with different, hypothetical figures than the actual data on taxes and assessments that formed the basis of his research. In short, blacks pay more, get less.)

The income from property taxes has also been diminished because of the continuing abandonment of housing stock, an inevitable component of the exploitation of neighborhood racial turnover by mortgage bankers, realtors, and slumlords. Tax delinquencies have been creeping up in recent years, and a study of TRUST, Inc. argues that the city’s taxing and assessing policies have often contributed to the process of abandonment by penalizing marginal residential properties. Among eight big cities, only Cleveland – that notorious victim of corporate bloodletting – lost a higher percentage of housing from 1960 to 1975 than Chicago did.

Governmental and banking neglect – and abuse – of black neighborhoods and their housing has hurt the whole city, not only blacks. Blockbusting real estate practices, red-lining, and irresponsible lending practices have all made quick, big bucks for realtors and financial institutions. But they have contributed mightily to the rapid abandonment and destruction of much housing. Likewise, slumlords refuse to pay taxes or maintain their buildings, allow them to run down while packing them to maximize rents, and then have local gangs set the torch for a final profit-taking on the fire insurance.

Consequently, the most dramatic decline in the housing stock has been in traditional black neighborhoods. Loss of such housing means, for the city and schools, loss of property tax revenue. It also contributes to the outward pressure of blacks seeking affordable housing, where they come into conflict with white working-class families for the few reasonably priced homes available. The decline of black neighborhoods and the competition for housing lessen the quality of life for everyone in the city, leading to precisely what government policy was supposed to prevent: “white flight.”

Now that the indirect influence of capital – business and the bankers – has made a thorough mess of the city and its schools, the proposed solution is to put capital directly in charge. In the process, we lose an important – if badly employed – democratic institution, public control of the schools. The New York model bodes ill for Chicago: devastating cuts in the schools and an attempt to weaken the school district’s unions have characterized the past several years there.

The Chicago Teachers Union is fighting back for its own interests now, and union president Robert Healey probably has the greatest support he’s ever had. But Healey and other union leaders deserve some criticism as well. They were aware of many of the school administrations’ misdeeds over the years, but they never fought Hannon and his predecessors on those issues as vigorously as they could have. Likewise, the union has not reached out sufficiently to parents and concerned community people to work cooperatively toward better education. In part, this has happened because the teachers union had its own cozy corner of the Machine. Teachers received fairly decent pay increases – although most are far from overpaid – and in exchange relative quiet was bought on many essential policy matters.

But the union now realizes that it is in a very serious fight for jobs and preservation of its contract. And at the teachers’ rally earlier this week, Healey and many other speakers, including State Treasurer Jerome Cosentino, overwhelmingly singled out one target for blame: the bankers, whom they correctly see as calling the tune far more than Jane Byrne, acting schools superintendent Angeline Caruso, or Board of Education president Catherine Rohter.

One of the banker’s best allies in this squeeze play has been Governor Thompson. Building his image as a tight-fisted tax cutter and playing to downstate and suburban antipathy toward Chicago, and its roughly four-fifths nonwhite school population, Thompson worsened the crisis by refusing to dig into the state’s $438 million cash surplus for a temporary loan to the schools. Thus the state has been used on behalf of the banks and against the school kids and teachers.

But who among these titans of finance cares very much about a bunch of black and Latino kids? “A lot of the problems of the schools come from their changing racial composition,” suggested retired teacher Tobey Prinz as she joined the teacher’s protest earlier this week. “I don’t think they give a damn about educating those kids.” That’s what a lot of black leaders are worried about. The Reverend Al Sampson told a south-side church meeting on the schools, “The central issue is who is going to make decisions about the mind of the black child – Wall Street and LaSalle Street or the people who have children in school.”

Our attention now is constantly focused on the short-term constantly focused on the short-term solutions, but it is important to be aware of the long-term solution implicitly being forged. Instead of a stripped-down school system run by a bunch of businessmen and bankers, whose allegiance is above all to their own profit, the city needs at least the following: (1) full collection of assessed taxes from businesses; (2) a new school board and new school administrators, with substantial representation of blacks and Latinos; (3) no School Finance Authority; (4) elimination of administrative waste and costly efforts to maintain segregation; (5) revenue brought in by correct assessments of businesses and a progressive tax (a graduated income tax is one possibility, a tax on professional transactions, such as with a lawyer, is another); and (6) a comprehensive development plan focused on the neighborhoods, not relying on tax abatements, that would aim to stabilize and preserve housing while creating jobs, either though private companies and through novel institutions such as municipal enterprises, cooperatives, or worker-community owned businesses.

Democracy is on trial now in Chicago, and the banks and businessmen find it not to their liking. The battle over the schools goes far beyond the important issue of preserving education; far beyond the issues even of who is paying for the schools and who is profiting form them. As the meetings in the black community and the teachers union rally suggest, more people are coming to see this conflict as an issue of popular democracy versus bankers’ rule. Don’t forget Woody’s warning.