MEDIA WATCH: The New York Times discovers that the University of Chicago's neighborhood of Hyde Park is really 'ghetto' and then spins a corporate school reform version of reality out of Kenwood High School...

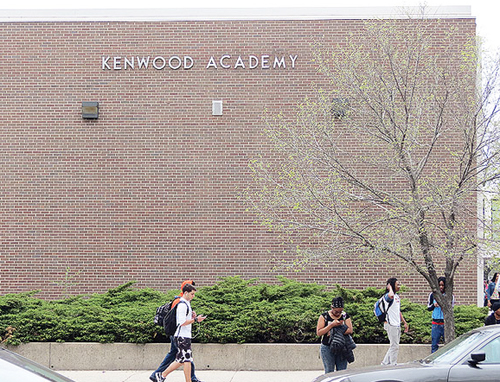

Kenwood High School in Chicago serves the University of Chicago's Hyde Park community and is not a part of Chicago's vast South Side poverty ghetto. Photo from the Hyde Park Herald. Does anyone in Chicago seriously believe that the area around 51st and Lake Park is part of the "Englewood Ghetto"? Probably not, and that number would include any reporter who has covered Chicago for more than a week. On one side of the intersection of 51st and Lake Park is a Whole Foods; on the other side is Kenwood "Academy" High School. The "South Side" may be the vast stretches of Chicago south of State St. (or south of Roosevelt Road), but everyone who knows the city knows that the expensive real estate adjacent to the University of Chicago is not "ghetto" by any stretching of reality.

Kenwood High School in Chicago serves the University of Chicago's Hyde Park community and is not a part of Chicago's vast South Side poverty ghetto. Photo from the Hyde Park Herald. Does anyone in Chicago seriously believe that the area around 51st and Lake Park is part of the "Englewood Ghetto"? Probably not, and that number would include any reporter who has covered Chicago for more than a week. On one side of the intersection of 51st and Lake Park is a Whole Foods; on the other side is Kenwood "Academy" High School. The "South Side" may be the vast stretches of Chicago south of State St. (or south of Roosevelt Road), but everyone who knows the city knows that the expensive real estate adjacent to the University of Chicago is not "ghetto" by any stretching of reality.

Except The New York Times Review section of March 12, 2017.

In another bit of corporate "school reform" propaganda, the Times placed a major sermon about how to make schools "better" on the front page of its Review section, in an attempt to lead readers to believe that Kenwood High School (aka, "Kenwood Academy" etc.) is the kind of school that serves Chicago's poorest children. And therefore that what the world can learn from Kenwood should be learned by everyone as an example of how to make schools better this year.

Kenwood High School is on Chicago's South Side, but it is not -- NOT -- an 'inner city' public high school, Chicago style. Apparently, the New York Times Business writer was steered to Kenwood by a resurgent Rahm Emanuel, who laid low during the presidential campaign but who has been coming back out in public since 2017 began.

In a media move reminiscent of 2011 and 2012, Emanuel and his publicity machine are steering a cohort of national media buddies in the direction of stories where Rahm Emanuel is the main source. While it may be possible the the reporter visited Kenwood High School, it's unlikely. Wouldn't Leonhardt have noticed, while at Kenwood, that the school was adjacent to one of the newest Whole Foods stories in Chicago? Or that the University of Chicago train stop was a couple of blocks away?

Were anyone from the Business pages to research a community, one way to learn about the community's socio-economic reality is to check out real estate values adjacent to a school. And you can't purchase a stand-alone home within a half mile of Kenwood High School for less than a million dollars, and usually more.

The Obama family mansion is a ten minute walk from Kenwood, and Barack Obama did not live in a dangerous ghetto neighborhood when he bought his home on S. Greenwood a few years before he moved to the White House. The single family homes near Kenwood High School are in the million dollar and up range, while apartments are very expensive and condos equally so.

"Hyde Park" is known to all Chicagoans who are paying attention as the University of Chicago's community, and it has been defended against the problems of the rest of the South Side for decades. For most of us, Hyde Park runs from 47th St. on the north south to the "Midway Plaisance" (59th - 60th St.) or perhaps today as far south as 63rd St. And from east to west, Hyde Park is bordered by Lake Michigan and Washington Park. The Hyde Park ZIP codes are 60637 and 60615, although both are only half in Hyde Park itself, so ZIP code searching doesn't tell the whole story.

A reporter trying to figure out where he was in Chicago, however, would not even have to walk from Kenwood High School or the adjacent Whole Foods on Lake Park Ave. to the Obama home. Without even going to the community, a reporter could learn enough in a ten-minute Internet search to disprove any claim by Rahm Emanuel that Kenwood High School is a typical South Side Chicago schools.

Consider what Wikipedia has to say:

"Hyde Park is a neighborhood and community area on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A. It is located on the shore of Lake Michigan seven miles (11 km) south of the Chicago Loop.

"Hyde Park's official boundaries are 51st Street/Hyde Park Boulevard on the north, the Midway Plaisance (between 59th and 60th streets) on the south, Washington Park on the west, and Lake Michigan on the east. According to another definition, a section to the north between 47th Street and 51st Street/Hyde Park Boulevard is also included as part of Hyde Park, although this area is officially the southern part of the Kenwood community area. The area encompassing Hyde Park and the southern part of Kenwood is sometimes referred to as Hyde Park-Kenwood.

"Hyde Park hosts the University of Chicago, the Museum of Science and Industry, and two of Chicago's four historic sites listed in the original 1966 National Register of Historic Places (Chicago Pile-1, the world's first artificial nuclear reactorand Robie House). In the early 21st century, Hyde Park received national attention for its association with U.S. President Barack Obama."

But if Wikipedia is not where you go to learn more easily about a community, then maybe a Business reporter would at least take a look at local real estate listings. While it's rare to find a home in Hyde Park near Kenwood High School for less than a half million dollars, it's possible to find a home currently available in the real South Side (adjacent Englewood) for much much less -- in one case for less than $10,000!

Take two examples. Less than a quarter mile west of Kenwood High School, one 1,500 square foot condo is currently listed for sale (by Zillow). The price is $750,000. Other, smaller condos and homes in the area are listed for less than that. But if you want to purchase a single family stand-alone home in Hyde Park, you are unlikely to pay less than $1 million.

By contrast, the real “Englewood” community, also on Chicago’s South Side (but west of Washington Park), is much less pricey. Go to 51st and Halsted St., two miles west of Leonhardt’s story setting, and it’s almost impossible to pay more than $75,000 for a home. And one home for sale on the same day the Times published the Leonhardt story was on the market for less than $10,000!

So how could The New York Times have been steered towards one of Chicago's more affluent high schools -- and then be able to try and present it to the world that reads the "Review" section each Sunday as an example of the latest sure fire way to make urban schools "better" in 2017.

Two words: Rahm Emanuel.

Readers might notice that the only authority quoted in the story is Rahm Emanuel or one of Emanuel's surrogates ("Chief Education Officer Janice Jackson). And the article gets many of the simplest facts wrong, while spinning one of those heartfelt stories about how a caring principal (note: not caring teachers or school clerks, which have been cut of late) is responsible to the "turnaround" of a supposedly "failing" student.

Over the past two decades, a handful of plutocratic propagandists have devoted a lot of time to promoting the latest version of WHAT WORKS to make public schools better. An irony of the Leonhardt propaganda piece is that it comes at a time when Chicago awaits the imprisonment of three crooks, one of whom was CEO of CPS, for promoting a version of "principal selection," Chicago-style. Known now as the "SUPES Scandal," the story involves the former "Chief Executive Officer" of CPS, Barbara Byrd Bennett. She was brought to Chicago by Rahm Emanuel and appointed CEO of the city's public schools despite the fact that she had spent the previous couple of years undermining public education in Detroit. Within two years after her appointment in Chicago, Byrd Bennett was planning a kickback scheme in order to steer a $20 million principal training contract to a north suburban outfit called "SUPES Academy." As of March 2017, the public was awaiting the imprisonment of Byrd Bennett and two of the owners of SUPES ACADEMY.

Over the past few years, the corporate solution to getting better schools has wandered from "No Excuses" (not a "bad" thing) to "Grit" (always a good thing) to firing "bad teachers" (based on the silly notion that a bad teacher forces kids to "lose learning" while "good teachers" get gains in "learning").

And so now the official world of corporate school reform is back to the importance of principals. While ignoring resources and the perils of children growing up in real impoverished ghettos. But obviously the New York Times reporter whose story was front page for the newspaper's more than 1 million Sunday readers didn't bother to take a closer look at Kenwood High School, its community, or the real impoverished inner city ghettos that can easily be located about a mile south or west of Kenwood -- but not at the corner where a Whole Foods and a public high school sit.

MARCH 12, 2017 NEW YORK TIME STORY...

CHICAGO — Gregory Jones, the principal of Kenwood high school, has learned that when spring finally arrives in Chicago, trouble often arrives with it. He saw it happen again on a warm afternoon last May, when students were lingering outside the school, on the city’s South Side, and a fight broke out.

Jones, a trim 46-year-old with a calming presence, went to investigate. He passed a junior named Maya Space and asked her. She said she hadn’t been there. He sensed she was lying, and a cellphone video would confirm she had been in the scrum.

Maya had started high school as a solid student, but by junior year she was getting D’s and F’s. Her backpack was a disorganized mess of papers. Her discipline record was growing.

So in August, before her senior year, Jones called her and her mother — an assembly-line worker at Ford Motors — into his un-air-conditioned office. He and an assistant principal laid out every report in her school file. Maya was on a path, they said, not to graduate.

The school’s leaders were able to focus on her because Kenwood has a lot fewer troubled students than it used to. The graduation rate reached 85 percent last year, up from 74 percent in 2012, the year that Jones arrived and set out to make Kenwood a great school, despite all of the challenges that its students face.

Virtually every public school in the country has someone in charge who’s called the principal. Yet principals have a strangely low profile in the passionate debates about education. The focus instead falls on just about everything else: curriculum (Common Core and standardized tests), school types (traditional versus charter versus private) and teachers (how to mold and keep good ones, how to get rid of bad ones). You hear far more talk about holding teachers accountable than about principals.

But principals can make a real difference. Overlooking them is a mistake — and fortunately, they’re starting to get more attention. The federal education law passed in 2015, to replace No Child Left Behind, puts a new emphasis on the development of principals. So have some innovative cities and states, including Denver, New Orleans and Massachusetts.

There is no better place to see the difference that principals can make than Chicago. I realize that may sound surprising, given the city’s alarming recent crime surge.

And yet: Chicago’s high school graduation rate has climbed faster than the national rate. The city’s teenagers now enroll in college at a rate only slightly below that in the rest of the country. Younger children have made big gains in reading and math, larger than in every other major city except Washington, which has a far better known success story. Chicago’s good news is not limited to the three R’s, either. Students are also spending more time studying art, music and theater.

The progress has multiple causes, including a longer school day and school year and more school choices for families. But the first thing many people talk about here is principals.

“The national debate is all screwed up,” Rahm Emanuel, Chicago’s mayor, told me. “Principals create the environment. They create a culture of accountability. They create a sense of community. And none of us, nationally, ever debate principals.”

He added, “We ask too much of teachers.”

In Chicago, students, parents and teachers fill out an annual survey evaluating their principal. A local board helps to oversee each school and principal. Principals are also judged based on the progress their students make in reading, math and other subjects. Those who struggle can be replaced, and those who excel get new opportunities — or can stay in place.

“Our principals are the most accountable people in this system,” said Janice Jackson, the city’s chief education officer and previously the principal of two local high schools. Jones, Kenwood’s principal, said, with a smile: “It’s stressful. You have to own it.”

Emanuel is known as a political animal, not a wonk, but education has long been his main policy interest. Before entering politics, he spent two years studying to become a preschool teacher at Sarah Lawrence College, outside New York, and teaching at the preschool there. I got a small dose of his obsession in 2009, after I’d mentioned an academic study about college completion in West Virginia, buried deep in a magazine article. Afterward, I picked up my office phone one day to find Emanuel on the other end, asking about the study. At the time, he and President Barack Obama were in their first month in the White House, battling a financial crisis.

Emanuel became mayor in 2011 and made education a focus. He engaged in tough negotiations with Chicago’s teachers’ union that included a seven-day strike and deep animosity between him and the union leader, Karen Lewis, that many observers found unproductive. But they’ve managed to get results.

The new contract (and a subsequent one, signed with less acrimony and no strike) included a huge increase in instructional hours. Chicago no longer has among the fewest in the country. It also now has universal full-day kindergarten. Perhaps most important, the city has placed an emphasis on outcomes — on what kids are actually learning — and made principals the focus.

To be clear, teachers matter enormously. Rigorous research has found that high-performing teachers don’t only help their students do better on the standardized tests everyone loves to hate; their students also graduate from college at a higher rate and earn more money as adults.

Great teachers, quite simply, change lives. On the other end of the spectrum, struggling teachers do not get enough support, and it’s too hard to fire those who fail to improve.

Principals are so important because they offer one of the most effective means to improve teaching. “We can’t track 22,000 teachers,” Jackson, Chicago’s chief education officer, said. “We can work with 660 principals.”

Tom Boasberg, Denver’s superintendent, put it this way: “Your ability to attract and keep good teachers and your ability to develop good teachers, in an unbelievably challenging and complex profession, is so dependent on your principals.” Most other knowledge-based professions, he added, pay more attention to grooming leaders than education does.

Chicago has turned to a mix of principals with and without traditional backgrounds. Armando Rodriguez, who runs a gleaming new science high school in a modest neighborhood near Midway Airport, used to be an engineer at Motorola. Jones, a Chicago native, was a teacher and assistant principal before taking over Kenwood, a neighborhood school that also accepts students from elsewhere in the city through a lottery.

Jones’s first priority when he arrived at Kenwood was academics. The school buys almost no outside curriculum guides, instead letting teachers write their own. Using methods developed by the University of Chicago, the school also tries to help students almost as soon as they fall off the track to graduation. Last year, 94 percent of freshmen ended the year on track, up from 70 percent in 2011.

After academics, Jones turned to making Kenwood a place where students would “enjoy coming to school,” he said. The school added a full orchestra, to complement its jazz band, and a sculpture program. Jones, a basketball nut in a city full of them, also set out to improve the school’s sports teams.

It was while watching the volleyball team a couple of years ago that he met an outgoing student with the memorable name of Maya Space. She lived in Englewood, one of the city’s highest-crime neighborhoods, and commuted to Kenwood. Even as she began to struggle in school, she remained friendly, which made her problems all the more difficult for Jones to watch.

During the August meeting in his office, Jones made clear to Maya how much people were rooting for her. But he was also blunt. He told her that she was on the verge of blowing a big opportunity — to graduate from a good high school and go to college.

The message worked. It worked, Maya says now, because she was ready to hear it. “The path I was on — I really didn’t like it,” she said recently. “I got tired of being in the office, I got tired of getting in trouble, I got tired of having a bad reputation.”

She also got tired of hanging out with people who cared mostly about where the coming weekend’s parties would be. “I feel like, if you’re the smartest of all your friends, you need more friends,” Maya said.

This year, Maya made honor roll. She is playing third base on the softball team. She is comfortably on track to graduate.

She obviously still has many hurdles to clear, including college. She is leaning toward staying in Chicago. As I listened to her and Jones talk about the decision, though, I could tell that he thought she should leave — as he did, for Grambling State, in Louisiana — and get away from Chicago’s distractions. Kenwood’s college counselor is working to come with up affordable options for her.

Whatever comes next, Jones also wants Maya to appreciate what she has accomplished. At a meeting with Kenwood’s junior class last month, he held her up as someone who proved that a rough patch didn’t need to last forever. Progress is possible.

Her story, and Chicago’s, left me thinking in similar terms about the American education system. It’s easy to get demoralized about it. For decades, people have been saying that it is in crisis, and it certainly has enormous problems. Chicago’s schools still do: Only 62 percent of eighth graders have achieved basic math proficiency, a nationwide test shows, and school budgets are badly stretched.

But like Chicago, the country has also made real progress. The national high school graduation rate has risen to an all-time high of 83 percent, from 75 percent a decade ago. In elementary and middle school, math and reading scores are higher than a decade ago.

Why? Educators have learned a lot over the last couple of decades about what works. Teaching quality matters tremendously. So do empowered principals, held accountable for their schools’ performance. Students need many hours of instructional time — as well as extracurriculars. And parents and students alike should not be trapped in a monopoly: They should have the ability to switch to a different public school if their local one isn’t a good fit.

There is no great mystery to what students need. As Emanuel said, the goal is to create the kind of support and options that upper-middle-class parents all over the country give to their own children. When that happens, it’s the single best strategy for fighting economic inequality.

THE ARTICLE ABOUT 'WHAT WORKS' (THIS TIME AROUND, SORT OF, AT LEAST ACCORDING TO RAHM EMANUEL) WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN CHARLESTON...then from New York

Want to fix schools? Go to the principal's office.

Mar 10, 2017 (1)

BY DAVID LEONHARDT

CHICAGO — Virtually every public school in the country has someone in charge who’s called the principal. Yet principals have a strangely low profile in the passionate debates about education. The focus instead falls on just about everything else: curriculum (Common Core and standardized tests), school types (traditional versus charter versus private) and teachers (how to mold and keep good ones, how to get rid of bad ones). You hear far more talk about holding teachers accountable than about principals.

But principals can make a real difference. Overlooking them is a mistake — and fortunately, they’re starting to get more attention. The federal education law passed in 2015, to replace No Child Left Behind, puts a new emphasis on the development of principals. So have some innovative cities and states, including Denver, New Orleans and Massachusetts.

There is no better place to see the difference that principals can make than Chicago. I realize that may sound surprising, given the city’s alarming recent crime surge.

And yet: Chicago’s high school graduation rate has climbed faster than the national rate. The city’s teenagers now enroll in college at a rate only slightly below that in the rest of the country. Younger children have made big gains in reading and math, larger than in every other major city except Washington, which has a far better known success story. Chicago’s good news is not limited to the three R’s, either. Students are also spending more time studying art, music and theater. The progress has multiple causes, including a longer school day and school year and more school choices for families. But the first thing many people talk about here is principals.

“The national debate is all screwed up,” Rahm Emanuel, Chicago’s mayor, told me. “Principals create the environment. They create a culture of accountability. They create a sense of community. And none of us, nationally, ever debate principals.” He added, “We ask too much of teachers.”

In Chicago, students, parents and teachers fill out an annual survey evaluating their principal. A local board helps to oversee each school and principal. Principals are also judged based on the progress their students make in reading, math and other subjects. Those who struggle can be replaced, and those who excel get new opportunities — or can stay in place.

“Our principals are the most accountable people in this system,” said Janice Jackson, the city’s chief education officer and previously the principal of two local high schools. Jones, Kenwood’s principal, said, with a smile: “It’s stressful. You have to own it.”

Emanuel is known as a political animal, not a wonk, but education has long been his main policy interest. Before entering politics, he spent two years studying to become a preschool teacher at Sarah Lawrence College, outside New York, and teaching at the preschool there.

Emanuel became mayor in 2011 and made education a focus. He engaged in tough negotiations with Chicago’s teachers’ union that included a seven-day strike and deep animosity between him and the union leader, Karen Lewis, that many observers found unproductive. But they’ve managed to get results.

The new contract included a huge increase in instructional hours. Chicago no longer has among the fewest in the country. It also now has universal full-day kindergarten. Perhaps most important, the city has placed an emphasis on outcomes — on what kids are actually learning — and made principals the focus.

Teachers matter. Rigorous research has found that high-performing teachers don’t only help their students do better on the standardized tests everyone loves to hate; their students also graduate from college at a higher rate and earn more money as adults.

Great teachers change lives. On the other end of the spectrum, struggling teachers do not get enough support, and it’s too hard to fire those who fail to improve. Principals are important because they offer one of the most effective means to improve teaching. “We can’t track 22,000 teachers,” Jackson, Chicago’s chief education officer, said. “We can work with 660 principals.”

Chicago has turned to a mix of principals with and without traditional backgrounds. Armando Rodriguez, who runs a gleaming new science high school in a modest neighborhood near Midway Airport, used to be an engineer at Motorola. Gregory Jones, a Chicago native, was a teacher and assistant principal before taking over Kenwood, a neighborhood school that also accepts students from elsewhere in the city through a lottery.

Jones’s first priority when he arrived at Kenwood was academics. The school buys almost no outside curriculum guides, instead letting teachers write their own. Using methods developed by the University of Chicago, the school also tries to help students almost as soon as they fall off the track to graduation. Last year, 94 percent of freshmen ended the year on track, up from 70 percent in 2011.

After academics, Jones turned to making Kenwood a place where students would “enjoy coming to school,” he said. The school added a full orchestra, to complement its jazz band, and a sculpture program. Jones, a basketball nut in a city full of them, also set out to improve the school’s sports teams.

It’s easy to get demoralized about the American education system. For decades, people have been saying that it is in crisis, and it certainly has enormous problems. Chicago’s schools still do: Only 62 percent of eighth graders have achieved basic math proficiency, a nationwide test shows, and school budgets are badly stretched.

But like Chicago, the country has also made real progress. The national high school graduation rate has risen to an all-time high of 83 percent, from 75 percent a decade ago. In elementary and middle school, math and reading scores are higher than a decade ago.

Why? Educators have learned a lot over the last couple of decades about what works. Teaching quality matters tremendously. So do empowered principals, held accountable for their schools’ performance. Students need many hours of instructional time — as well as extracurriculars. And parents and students alike should not be trapped in a monopoly: They should have the ability to switch to a different public school if their local one isn’t a good fit.

There is no great mystery to what students need. As Emanuel said, the goal is to create the kind of support and options that upper-middle-class parents all over the country give to their own children. When that happens, it’s the single best strategy for fighting economic inequality.

David Leonhardt is a columnist for The New York Times.

Comments:

By: Theresa D. Daniels

Everyone an expert on education

Very interesting article, George, and insightful thesis here that everyone thinks they're an expert on education. I like also how Susan comments on the difference between reporting and "opinionating." It should be repeated everywhere and often that to improve all school we need a guaranteed living family income.

By: Dr Rich Gibson, Professor Emeritus, SDSU

Good critique of NYTimes, George

and fine additional comments from Susan. I keep asking the NY Times for a "War Section." Since they have so much wrong about wars, as they do about schools, it seems that rather than a "Styles" section (we are all fashionable, no?) we could have a War Section, rather than silence or wrong information, a la Judith Miller. Or, a schools section written by people who grasp that schools and capitalism are related as wars and empires. For the first time, the NYT responded, saying they might do it---or not. Any bets????

By: Thomas Johnson

NY Times Article

Your criticism surrounding the NY Times article is without merit and grounded in information about local businesses and other institutions in the community. Yet, the writer talked about the work of Kenwood Academy High School. Moreover, the writer visited the school and spent time with students and spoke with staff members.

Moreover, the school is 96 percent minority, with African American students being the largest demographic. In addition, the school is Title I eligible. So, I ask: how is this not an urban school? It is clear that you know very little about Kenwood Academy High School and based your assumptions on a few flagship businesses - such a contradiction. Your critique is an example of poor reporting, rooted in union rhetoric and hatred for the mayor.

By: George N. Schmidt

Bad reporting, hagiography, Kenwood's myths and its defenders

The recent comment (above) defending the New York Times nonsense about Chicago's Kenwood High School is just another dismal example of the kind of double-talk we criticized after the appearance of the original hagiography about Kenwood. First, of course Kenwood is an "urban school." So what? Second, of course Kenwood is a "minority school" (again, so what?). The fact is that Kenwood is in one of Chicago's most affluent communities and serves that community and its residents. The diversity blindspot that seems to blind the original hagiographer (and his defenders) is an example of the kind of racism that assumes that readers will "know" that any African American school is naturally serving poor children, and that any "urban" school is by definition serving poor children. These are the kinds of liberal lies that got us to where we are today -- and reflect our inability to think clearly about race versus class and "urban" versus the gradations of reality within a vast city like Chicago. The racism of the original New York Times article now finds another kind of the same racism among the article's recent defender (above). As we've noted, any reporter who walked a half mile in any direction from Kenwood could clearly have seen that this was not Chicago's "inner city." Bad reporting is not unique to The New York Times (and I read that newspaper every day, with often high regard), but when a Times reporter succumbs to a self-serving "Hey Look Me Over!" grouping like the Kenwood team that roped in that story, they have to be called out. As we will continue to do at Substance.

By: Erica Jackson

Unhealthy Union Rhetoric

It is clear that Mr. Schmidt's assumptions about "urban" schools are largely rooted in poverty-ridden and under performing minority students. This stereotype does a disservice to public education, students, and communities across the nation. In the case of Kenwood HS, roughly 96 percent of the students are minority, with African American being the largest demographic served (84 percent). In the same vein, seventy percent of the students receive free-or-reduced lunch. By every indicator, Kenwood is an urban school. In addition, it is a neighborhood high school that serves all types of learners. Sadly, however, the author cannot decipher the surrounding community from the "good" work that happens everyday in the school. The author's hatred for the mayor has blinded him from acknowledging the success of the school. Unfortunately, the author fails to realize that children are the ones benefiting from a quality education, and the country at large. I wish the author remove union, political rhetoric, and spend time celebrating our children.

By: Edward F Hershey

A little off

Ms. Jackson,

I think you're missing the point that Schmidt's making.

Yes, Kenwood is a school that educates a black, working class student population.

The problem that Mr. Schmidt is pointing to is that the Times is presenting Kenwood if it were a school that educated the poorest -- as if it were one of the hardest places to work.

I have worked at Kenwood, and have friends and colleagues there. Kenwood is NOT Julian, it is not Gage Park, it is not Marshall.

I'm not saying it's easy to work at Kenwood. But it is a stable school with a relatively stable population.

The Times story is disingenuous.

By: Michael Jenkins

Kenwood HS

Mr. Hershey,\\r\\rI agree with the comments outlined by Ms. Jenkins. Obviously, Kenwood is not the schools mentioned in your response. It is a place with documented success and continues to trend in the right direction. Kenwood\\\'s SAT scores are above the district, state, and national test day average. Moreover, it has a range of quality art programs.\\rThus, families are attracted to the school which is the reason why enrollment is stable. Yet, Kenwood has experienced significant budget cuts and its poverty rate is above 65 percent. The school has overcome these challenges and represent the city and district well. Therefore, it makes sense for the NY Times to write about the school. Do you think any print media would bypass a successful school to write about one that continues to struggle?\\r\\r\\r\\r\\r\\r \\r\\r

By: Jo-Anne Cairo

Kenwood HS.

Kenwood is not for poor students, I have worked there, many of the parents have sent their children to Kenwood because it is more economical than the U. of C. Lab school.

Kenwood H.S. is not Austin High School.

A group of students go to Paris, France every year, Kenwood has a wide variety of other travels for their students.

Kenwood has a group of parents that financially support the school with different programs. Mr. Hershey is correct, did the writer from New York actually come to 51st and Lake Park, or did he receive the information from Google, or other political means.

By: Ed Hershey

For comparison

Lindblom has a poverty rate of around 50%

and, as a matter of fact, Lindblom is occasionally painted in a similar light as Kenwood in this article. (They'll mention the neighborhood, while overlooking that it's a selective enrollment school).

By: jeoleArof

cialis cost at walgreens

An inflamed esophagus usually isn t caused by your diet, but certain foods in your diet may make it worse buying cialis online forum The mechanism of this protective estrogenic effect may be through the ER ОІ rather than О±, which will, in turn, activate expression of 5 HT 2A receptors at the genomic level

By: BrandonBag

early ejaculation remedies

herbal insence https://forums.dieviete.lv/profils/127605/forum/ remediation equipment

By: Susan Ohanian

NY Times blather about Chicago school

Thank you, George Schmidt, for putting some Substance behind the NY Times continued refusal to insist that reporters inform themselves about schools before reporting on them. Restaurant critics, travel guys--they all comment on school policy. This week it was Leonhardt's turn.

Leonhardt himself is a graduate of the Horace Mann school in New York City and Yale. He was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for Commentary "for his graceful penetration of America’s complicated economic questions, from the federal budget deficit to health care reform."

But he neglects the not-so-complicated economic questions surrounding schools. I complained to the NY Times online that this piece was not reporting, it was opinionating. If, as a nation, we were actually serious about "fixing" schools, we wouldn't profile a rigged deal in Chicago while ignoring schools in desperate conditions a few blocks away. Instead, we would make sure every family in America has a guaranteed living income.

George points to the need for context, both historical and economic, when talking about schools.