Your high school journalism teacher was a serial sexual predator

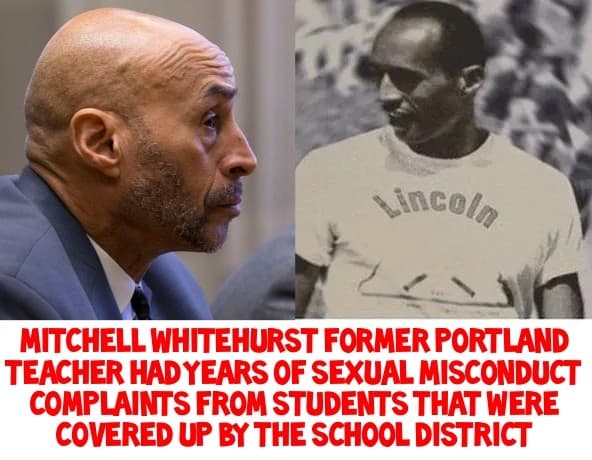

Mitch Whitehurst, ex-teacher accused of decades of abuse went nowhere, records show

Mitch Whitehurst, ex-teacher accused of decades of abuse went nowhere, records show

https://www.oregonlive.com/education/2016/09/years_of_sex_misconduct_compla.html Inspired in part by Bethany Barnes’ 2017 investigation into high school sexual predators, Insider’s Matt Drange went back to his alma mater and uncovered some ugly truths.

By Colleen M. Connolly & Alexander Russo June 8, 2022

All too often, teachers prey on students, and schools, districts, and others let them continue to do so.

Then, when the behavior is finally addressed, the offenders are often left to find a job at another school or district — a process commonly known as “passing the trash” that surprisingly few states prohibit.

But rarely is it revealed that a reporter’s own former journalism teacher has been a sexual predator. And even more rarely does that reporter report and write the story that reveals the long-running problem.

That’s what happened on May 16, when Insider investigative reporter Matt Drange published a gripping account uncovering his high school’s beloved journalism teacher’s predatory behavior and the complicity of the school and district that had employed him and the students and teachers who looked the other way.

https://www.businessinsider.com/rosemead-high-eric-burgess-sexual-misconduct-investigation

“Boundaries between teachers and students were nearly nonexistent,” Drange writes about his high school experience. “I grappled with whether I’d been a part of a community that allowed troubling behavior to go unchecked.”

The story clearly hit a nerve. Roughly 8 million people have read the story so far, and the district still hasn’t responded much or admitted it did anything wrong, fueling additional complaints and calls for resignations. It’s been featured in newsletters including Local Matters, CJR’s Media Today, the Poynter Report, and the Sunday Long Read.

In the following interview, Drange describes the tidal wave of reactions to his piece, decries the lack of coverage of the problem from local news outlets, and reflects on his desire to keep the women who have come forward to describe their experiences the focus of his story.

He also reveals that some of the clarity and inspiration that fueled his reporting was the result of reading Bethany Barnes’ award-winning 2017 investigation Benefit of the doubt, about a Portland teacher who evaded allegations of sexual misconduct for years.

https://www.oregonlive.com/education/2017/08/benefit_of_the_doubt.html

“I had this feeling of deja vu that I couldn’t exactly pin down, but it was strong,” he said about reading Barnes’ piece. “And that’s when I knew like, ‘gosh, I need to do something about this. I need to look into this. I’m a reporter. I know what to do.’”

I grappled with whether I’d been a part of a community that allowed troubling behavior to go unchecked.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What’s the reaction been to your piece?

MD: So the story at this point, I think has been read by about 8 million people. And I’ve heard from people all over. So, you know, people back home, people in journalism, people in education, people in sex abuse, people in law enforcement, parents, students. I’d say the overwhelming response has been one of ‘Oh my gosh, this is so sad. And it reminds me of _____________ ‘ [fill in the blank/name of teacher they remember]. That has been by far the most common reaction. So if the last week has taught me anything, it’s that this behavior is not unusual.

What role did the school or district play in allowing this teacher to do what he did for as long as he did it?

MD: The school was made aware several times over the years of allegations against this teacher. And as I say in this story, little to no action was taken every time until 2019, when he was put on leave with pay while they investigated a relationship that he’d had with the former student. And really the impetus for that was screenshots of sexually explicit messages that the teacher had exchanged with the student and were briefly posted a social media. It wasn’t a secret anymore at that point. [However] there were times over the past 20 years prior to that where there had been red flags raised and little action was taken.

What’s the district’s response been since the story was published?

MD: Since the story was published, the district has issued several statements that most people that I’ve been in touch with in the community and on campus feel have not helped in any way. The district has not apologized, has not said that they have done anything wrong. It has, in part, fueled some of this intense response happening right now in the community where people are demanding that people lose their jobs, that action be taken, that steps to better educate staff and students be taken.

For the latest update on Drange’s investigation, read here.

‘I need to look into this. I’m a reporter. I know what to do.’

What was it like for you to cover something this close to home? And do you think that journalists, or in particular education journalists, have a responsibility to look back at their own school experiences?

MD: I wouldn’t say that it’s anybody’s responsibility to cover any particular story. And I don’t even know that I would recommend that most reporters do this. The work comes at a cost. And so, for me, that is something that I accepted a long time ago, but I wouldn’t want to put that burden on anyone else. And I don’t think you’re a lesser reporter if you don’t want that burden.

I just felt that if I didn’t tell the story that no one would, and I, in fact, tried to give it away to other reporters at various points. I tried to give it away to reporter friends of mine at large publications. And they told me that it sounds like a great story, but it would be so much better if you told it yourself. Stories about this kind of behavior are very common, but stories told in the first person about this kind of behavior where the teacher was your teacher, I don’t know of any other story like that.

So I think that was sort of the point that my friends were trying to make. And in hindsight, I’m glad they made it because they’re right. Even though it was very difficult, not just for me, but for many people close to me. My family, my friends, several people back home have told me something to the effect of, ‘you know, reading your story destroyed a part of my childhood, but I’m really glad you did it.’ So I wouldn’t try to put that on anyone else. It is quite heavy.

Previously from The Grade: Secret agreements in special education

I don’t even know that I would recommend that most reporters do this. The work comes at a cost.

What was it like reporting a first-person story? Was it particularly different or difficult?

MD: Yeah, it was very difficult for me and very uncomfortable, both from a reporting standpoint, but also a writing one. I took great care in the story and I’m grateful that my editors helped me with this. I did not want to be the center of the story. That was very important to me. I wanted to be a way into the story, perhaps a unique angle into the story. But it was important to me that the women who came forward and who trusted me with their stories were the primary characters in the narrative. I didn’t want to get in the way of that. And I feel like we did a good job of that in the story, but it was something that I worried about constantly because I feel as a reporter it’s my job to tell other people’s stories.

What are your personal reflections about having been there while some of this might have been happening?

MD: I also talked about my personal relationships and that guilt that I feel as being part of that culture because I was part of that culture. In the wake of the #MeToo movement it was both very clear to me and also very painful. And I think that is what a lot of people back home — and in general, people who were not necessarily that close to this — are grappling with right now. I’ve heard from a lot of readers. I was part of the culture that looked the other way at things that I mentioned in the story, such as cheerleaders sitting on a teacher’s lap between classes. I saw the blurred boundaries constantly, and I knew at the time, as I say in the story, that my journalism teacher had had a child with a former student. That was a very open secret. I knew all those things, but none of them — because of the culture — seemed that noteworthy at the time.

It was important to me that the women who came forward … were the primary characters in the narrative.

What was the turning point for you in terms of understanding that open secrets and blurred boundaries could be sexual assault?

MD: It wasn’t until I read a friend of mine’s story, Bethany Barnes, who you probably know, in The Oregonian, Benefit of the Doubt. I read that and it just really resonated with me. I had this feeling of deja vu that I couldn’t exactly pin down, but that was strong. And that’s when I knew like, ‘gosh, I need to do something about this. I need to look into this. I’m a reporter. I know what to do.’ At the time, I didn’t know that the story was going to be about my journalism teacher. I just knew that I saw lots of blurred boundaries and that in hindsight, there were probably more.https://www.oregonlive.com/education/2017/08/benefit_of_the_doubt.html

Above: How Bethany Barnes became a star education reporter (featuring her story about a serial sexual predator, Benefit of the Doubt).

Why do you think nobody else, like the LA Times, has covered this story yet?

MD: I think it speaks to, in some ways, the culture and the community. It’s difficult to overstate the trust that I have in my community right now. I think people are sharing stories with me that they wouldn’t share with another reporter because of that personal connection, because I went to Rosemead High School, because I’m an alum, because I’m of this community and I care about it deeply. The personal side kind of cuts both ways. It makes it more difficult for me to work on, but I think it makes it easier for people to trust me. As far as other outlets and what efforts, if any, they made to report on this, I don’t know. I can say that in particular, with regards to the LA Times, a lot of people where I grew up have felt over the years that the LA Times has routinely turned its back on the San Gabriel Valley, which is in its coverage area and is largely an Asian and Latino community. A lot of people there feel like this is just another example of that.