Betsy DeVos’ Legacy: Transforming How The Education Department Treats Civil Rights

Betsy DeVos’ Legacy: Transforming How The Education Department Treats Civil Rights

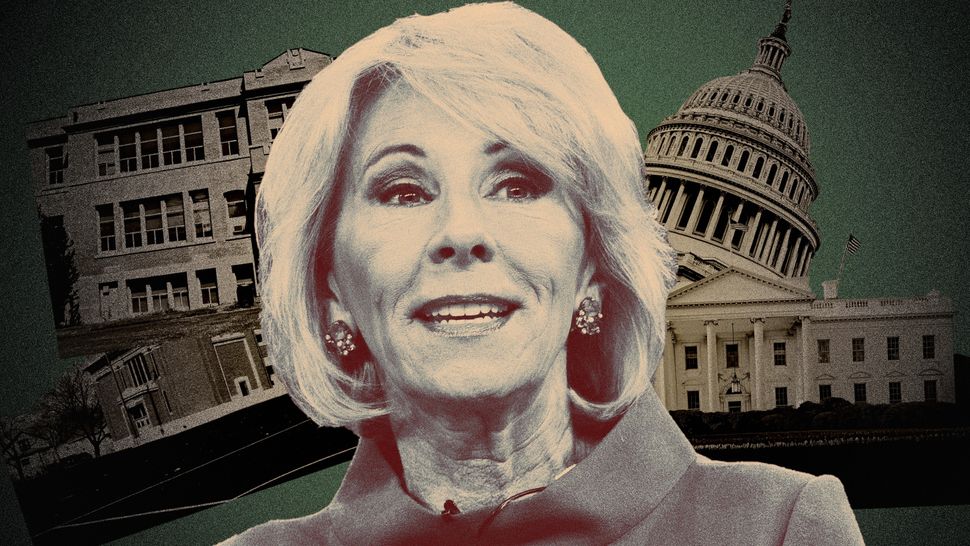

The Department of Education, under Secretary Betsy DeVos, has been characterized by disorderly decision-making processes, say some employees and advocates.ILLUSTRATION: DAMON DAHLEN/HUFFPOST; PHOTOS: GETTY

The Department of Education, under Secretary Betsy DeVos, has been characterized by disorderly decision-making processes, say some employees and advocates.ILLUSTRATION: DAMON DAHLEN/HUFFPOST; PHOTOS: GETTY

By Rebecca Klein 11/16/2020 09:55 am ET

The Education Department has been slow to investigate complaints of discrimination related to COVID-19, HuffPost has learned. Employees say it’s part of a pattern of disorganization that has emerged under Trump.

The Department of Education, under Secretary Betsy DeVos, has been characterized by disorderly decision-making processes, say some employees and advocates.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights has spent months failing to make meaningful progress on urgent complaints of education discrimination relating to COVID-19, even as the pandemic continues to turn schools upside down and put vulnerable students at an even further disadvantage, according to multiple sources. In September, employees in at least some of the department’s regional offices were informed that civil rights complaints specific to COVID-19 ― such as for children who have not been receiving accommodations for their disability during remote learning ― would require scrutiny from the highest levels of management, a development that would substantially slow the pace by which any of these complaints could get resolved.

A parent and an advocate have also been given the message that coronavirus-related complaints are unlikely to be addressed in the near future. After disability rights advocate Marcie Lipsitt filed several complaints on behalf of families whose children with disabilities were not receiving appropriate services from their school during shutdowns, she received a call from a department attorney informing her that complaints referencing COVID-19 were receiving greater scrutiny than non-coronavirus complaints and rewriting them without references to the pandemic could help them get processed faster.

HuffPost has also reviewed an email from regional management to a group of employees telling them that COVID-19 complaints are requiring additional review from headquarters. Still, the Education Department has denied that such levels of scrutiny are taking place.

“This information is categorically false and represents the viewpoint of a low-level employee who has not been fully informed or brought up to speed on the clear directive given by [headquarters] to move forward on all COVID cases without delay,” Education Department spokeswoman Angela Morabito wrote to HuffPost. “Regional Directors have been instructed to take all necessary steps to move forward with COVID cases expeditiously. Unless they present novel COVID-related issues, those cases are not being reviewed by Headquarters.”

Multiple employees and advocates say that during a national education civil rights emergency, the Department of Education is effectively not addressing problems that are currently harming students as a result of the pandemic. The decision, they say, is not only baffling, but emblematic of some of the disorderly decision-making processes that have come to characterize the agency, especially during the past four years, under President Donald Trump and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. Another employee says they believe department leaders are still figuring out how to respond to these complaints during an unprecedented time.

The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) is one of the most impactful agencies within the Department of Education, overseeing and enforcing federal education civil rights laws. In addition to putting forth guidance on how schools and universities should handle civil rights laws and enacting regulations around these issues, it receives thousands of discrimination complaints a year from families and students, to be resolved by the department’s attorneys. Over the past four years under DeVos, its priorities have been transformed, according to interviews with eight current and recently departed OCR attorneys and several other civil rights advocates who regularly interact with the agency. Beyond the agency’s most famous moves ― like striking down guidance designed to protect transgender students and rewriting rules governing campus sexual assault ― these employees describe a lack of leadership competence, with frequent process changes creating a sense of chaos and disorganization, a perception of those at the top cutting procedural corners to advance a political agenda and an overall push to take a more hands-off approach to enforcing civil rights in schools.

Morabito, the Education Department spokesperson, vigorously refutes this characterization of OCR, writing that such a statement “furthers the false narrative of those within the agency who oppose the Trump Administration at all costs, and choose to ignore the accomplishments of the last four years,” pointing to efforts to hold institutions like Michigan State University accountable for failing to protect students from predators like Larry Nassar. Ken Marcus, who led the agency between 2018 and summer 2020, also told HuffPost he believes the agency has not only become more efficient, but more effective, highlighting the number of cases resolved with change under his tenure and proactive investigations launched into problems of sexual violence in K-12 schools.

“I would love to see the next administration try to challenge our record on case resolutions,” said Marcus.

When it comes to COVID-19 complaints, OCR regional management told a group of employees this fall over email that top leadership needed time to formulate a plan on how to handle these new issues, though it has already been months.

In the meantime, students facing potential discrimination are left in a lurch. One mother, Stephanie Onyx of Michigan, filed complaints for each of her children with special needs, after they stopped receiving disability-related services they’re legally entitled to ― like occupational, physical and speech therapy ― amid remote learning.

Lipsitt filed a third complaint on behalf of Onyx, specifically referencing COVID-19, but nearly otherwise identical.

Onyx says she was told by an OCR attorney in early November that while they could start addressing her first two complaints, the third that specifically referenced COVID-19 would be put on the back burner.

“He told me on the phone anything COVID-related is being sent to headquarters,” Onyx said.

OCR attorneys say they have been left powerless to help these families.

“That’s kind of consistent with what we’ve come to expect. We have a staff of skilled passionate attorneys who want to do their jobs and I think many of us feel like we just can’t,” a current OCR attorney told HuffPost. HuffPost is providing anonymity for current and former employees who requested it out of concern over facing professional repercussions.

DeVos’ pet issue has always been touting private school choice, which gives children further access to private schools via taxpayer-funded scholarships. However, her work overseeing how the department handles civil rights issues may prove to be one of her most enduring legacies. While the agency’s most public moves have had an obvious impact on vulnerable students, employees say they also worry about the consequences of the more subtle changes in how the agency handles run-of-the-mill civil rights complaints.

With the recent election of Joe Biden, civil rights advocates and attorneys are looking ahead, but they worry the damage they believe DeVos inflicted on the agency might be difficult to reverse. Undoing the agency’s overhaul of Title IX regulations would likely be a lengthy process. Legions of top employees have long left. And vulnerable students and families might still believe the office is not on their side, making them less likely to file complaints when issues arise.

“So much damage is already done. People’s confidence is low,” said a former OCR attorney who left the department in early 2019. “The advice I give people now [on filing complaints] is why bother. I don’t think that attitude will change. I think that’s how a lot of lawyers and advocates see it.”

The Beginning Of A New OCR

Almost immediately after taking control of the Education Department, DeVos’ OCR rescinded a piece of guidance that directed schools to allow transgender students to use the bathroom that corresponded with their gender identity. A few months later, she and her newly appointed OCR leader, Candace Jackson, began taking a fresh look at Obama-era Title IX guidance for how schools handle allegations of sexual assault.

Jackson made headlines at the time for suggesting that 90% of sexual assault allegations “fall into the category of ‘we were both drunk,’ ‘we broke up, and six months later I found myself under a Title IX investigation because she just decided that our last sleeping together was not quite right,’” per The New York Times.

Behind the scenes, a small group of career attorneys were working closely with Jackson on a project they thought could help bolster the previous pieces of Obama-era Title IX guidance. The attorneys were tasked with assisting Jackson in devising a subsequent document to clarify the earlier guidance and address concerns of unfairness during school proceedings, a former OCR attorney who left in 2018 told HuffPost.

Months into the task, though, they had the rug pulled out from underneath them, the attorney says. DeVos revealed during a speech at George Mason University in 2017 that her department would “replace the current approach” toward addressing sexual misconduct, citing anecdotes of students who she said failed to receive due process. The attorneys, who were watching the speech in a conference room with Jackson and other department staff, were stunned. They were soon made aware that Jackson had been working with political appointees to rescind the 2011 and 2014 guidance and develop a replacement guidance, undermining the very task she had assigned to them.

In an email, an Education Department spokesperson said this description of events isn’t true.

The former OCR attorney said, “It was clear to us that [DeVos] didn’t understand the 2011 and 2014 guidance because much of what she cited in her speech [as problems caused by them] would have actually violated the guidance.”

“That was really upsetting, especially because of all the work we were doing with Candace beforehand, educating her about issues that some of us had been working on for years and thinking we were just building on the earlier guidance, without knowing that all along she was working on rescinding them. … We had a hard time trusting her then. I don’t know if it was to distract us or what the point of that was,” said the attorney. The rescission of the guidance threw the process for handling current Title IX cases into disarray, though, under the Obama administration sexual violence cases were already moving impossibly slow and were accompanied by their own host of frustrations, multiple employees said.

Another attorney says that after the rescission they felt confused and lacked clear instruction about how to handle sensitive legal matters surrounding sexual harassment and assault.

“I felt like I could do disability civil rights work. I was unsure about Title IX ― what an investigation would look like, what an outcome would look like, what the standard is,” said the attorney, who left the job out of frustration with the working environment.

President Donald Trump and DeVos make “U” symbols with their hands while posing with the Utah Skiing team as they greet members of championship NCAA teams at the White House in 2017. While DeVos was in charge, the Education Department changed its approach to addressing sexual misconduct cases.

After Trump was elected, there were also almost immediate changes to the department’s internal processes, processes that would impact whether a civil rights complaint was thrown out or saw the light of day.

Under the Obama administration, certain types of discrimination complaints could trigger attorneys to look for evidence of systemic bias within institutions. While potentially impactful, these investigations could be labor intensive and cumbersome, lasting for years on end. Under DeVos’ reign, employees were asked to focus on the individual instead, in part to promote expediency. Some employees were happy for the relief, but the new system also sometimes meant that institutions that might be perpetuating systemic discrimination could be let off the hook. “There were a lot of staff who were disgruntled [under the Obama administration], because even if you’re investigating something, if it’s not resolved you don’t get that satisfaction,” noted one former attorney who left their job in 2018. “I think somewhere in between what was happening before this administration and a drastic shift to limit scope is probably the right place to be. But it was troubling to see the extent to which they moved to find reasons to close out complaints.”

The department’s commitment to quickly working through grievances came to a head in spring 2018, when the department issued an update of OCR’s Case Processing Manual ― the legal document that helps dictates the process by which department attorneys handle complaints.

The update immediately resulted in litigation, after its changes allowed attorneys to automatically dismiss complaints from people or groups who frequently file grievances, if employees determined such complaints placed “an unreasonable burden on OCR’s resources.” Lipsitt, the disability rights advocate, for example, files hundreds of complaints a year dealing with website accessibility for students with disabilities. The update also eliminated the right of students and families to appeal decisions. The National Federation of the Blind, the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates Inc., and the NAACP sued, claiming the agency has a duty to investigate discrimination complaints to the best of its ability. Advocates questioned why the agency would want to automatically throw out complaints when real instances of discrimination might be taking place, just because they were filed by the same person. The update seemed designed to silence students and their families and prevent them from obtaining justice, they said.

At the time, Education Department spokesperson Liz Hill told The New York Times that the changes were representative of their “commitment to robustly investigating and correcting civil rights issues” and “improving OCR’s management of its docket, investigations and case resolutions.”

Months later, the agency put forth an updated manual once more, riddled with typos in the table of contents and rolling back some of its original updates. “CASE pLANNING” reads one section in the manual’s table of contents, a sloppiness advocates feared was a reflection of the department’s commitment to the issue. The table of contents’ subheads skip from “ARTICLE III” to “ARTICLE V.”

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

A case processing manual update was released in November of 2018.

The revisions, Morabito says, were driven by changes in OCR leadership, noting that Jackson had recently been replaced as head of the agency by her successor, Ken Marcus. Marcus also told HuffPost that after his appointment “one of the first things I wanted to do was review the CPM, including but not limited to, the changes made earlier in the administration.”

In February of this year, the civil rights groups and the Department of Education resolved the issue in court, with the department agreeing to reopen the complaints it had previously dismissed and pay the plaintiff’s legal fees.

Attorneys say while these changes often fly under the radar and garner less public outrage as a guidance rescission, they can prove equally, if not more, dangerous.

“The CPM changes were really disheartening … all these little pin pricks unite into a gaping wound,” said a former OCR attorney.

Another attorney, who still works at the department, says they believe this is part of the agency’s current modus operandi: to throw out as many complaints as possible and reduce the agency’s footprint as much as possible.

“It’s just shrink, shrink, shrink, get out of the locals’ ways,” they said.

A New Leader Takes The Helm

To Jackson’s credit, employees say she was thoughtful and warm, and took pains to solicit input, even if such suggestions rarely changed her mind. On a personal level, multiple attorneys say she was well-liked, despite political differences with some of the career staff. Employees say her successor, Ken Marcus, confirmed in 2018, interacted less with the rank and file and seemed less interested in their perspectives. In response, Marcus wrote over email that he “depended on [talented career staff] heavily. Of course, we relied more on some than others: some had more seasoning, broader experience, and sounder judgment.”

Marcus, who previously served in the same capacity under President George W. Bush, had a specific interest in protecting students against what he saw as a rising tide of anti-Semitism on college campuses, especially as it relates to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

He reopened an investigation into a complaint alleging anti-Semitism on campus at Rutgers University, which had previously been closed under the Obama administration. Such a move, to reopen a case that had already been investigated, was unprecedented, said a former attorney, and in the attorney’s view reflected a willingness to bend the rules in service of a political agenda.

Marcus says such an assertion reflects a misunderstanding of the facts surrounding the case. An appeal to the case was filed several years ago, as allowed for the Case Processing Manual at the time. While the CPM went on to eliminate appeals, once the process was reinstated, he decided to move forward with the process. “It wasn’t particularly unusual,” he says. The attorney’s confusion shows that there was already distrust surrounding the incident.

At the same time, a March 2020 complaint from a number of groups including Palestine Legal, urges the inspector general for the Department of Education to investigate the incident, writing that reopening appeals is distinctively rare: Of over 180 appeals resolved between 2014 and 2018, only two were reopened, it says. The letter alleges that Marcus gave this case special treatment, though OCR is supposed to act as a legally neutral body.

Under his watch, Marcus helped the White House adopt a broader definition of anti-Semitism that allowed Judaism to be defined as a race or national origin in civil rights cases, making it easier to crack down on potential discrimination. In December 2019, Trump signed an executive order threatening to withhold federal money from universities seen as fostering anti-Semitism, an order critics feared would stifle free speech as it pertains to pro-Palestine activism.

Marcus also oversaw the rescission of Obama-era guidance designed to protect students of color from discriminatory disciplinary processes and guidance around how colleges could consider race in admissions. Most significantly, he led the department in crafting a new detailed and complicated rule governing Title IX and sexual harassment and assault on college campuses ― a rule that contains a more severe definition of sexual harassment, helps bolster the rights of the accused, and contains a higher standard for holding schools liable as they will no longer be held responsible for sexual violence occurring off-campus.

The rule, more than 2,000 pages long, has been decried by civil and women’s rights groups and some university administrators, while receiving praise from conservatives, men’s rights groups and some scholars. It has been subject to a litany of litigation from advocacy groups and attorneys general from 17 states.

Marcus’ actions promoting the rights of Jewish students were expected, but his views on other civil rights issues were lesser known. In the end, he worked to curtail the legal protections offered to transgender students, say advocates, pointing to a complaint filed by the Alliance Defending Freedom, an organization dedicated to fighting LGBTQ rights.

The complaint sought to prevent an athletic conference in Connecticut from allowing transgender students to play on the teams that correspond with their gender identity, claiming it gave them an unfair advantage. One former OCR attorney, Dwayne Bensing, was concerned about the way the agency quickly pushed the complex complaint forward, and in August 2019, he leaked internal emails pertaining to the case to the news outlet The Washington Blade. The emails showed attorneys expressing confusion over what legal framework to apply to the complaint, even after they had already decided to open it. The emails also showed that Marcus was involved in handling the complaint from its inception, which Bensing found worrying.

By December, he was forced out of his job, as first reported by HuffPost, even though he had a history of excellent performance reviews, and has since filed whistleblower and retaliation complaints. His whistleblower complaint was closed after the Office of Special Counsel said it was “unable to conclude that there is a substantial likelihood” the Department of Education had violated the law on its handling of the complaint. His retaliation complaint is ongoing.

“Other than their passion project of hurting trans kids, what else is the department or has the office done? Who are they helping?” said Bensing.

The Department of Education has said Bensing’s analysis of the situation is “based on incomplete information.” Marcus wrote over email that while he was “aware of the allegations ... I do not know of any deviations from the CPM in that case.”

Later, after Marcus left the department, it threatened to withhold federal grant money from Connecticut schools that did not withdraw from the athletic conference that allows transgender students to play on the team that corresponds with their gender identity, The New York Times reported. The grant money is designed to help schools spur desegregation.

Members of the audience wait for the start of DeVos’ confirmation hearing to be secretary of education in 2017. The #DearBetsy hashtag was part of a campaign urging DeVos to protect campus sexual assault guidelines laid out by Title IX.

In one of his final moves, Marcus oversaw another update to the CPM, this time making changes that some current and former OCR employees say created new power for institutions accused of misconduct. These most recent changes allow the department to share its draft investigatory findings with schools, giving institutions an opportunity to “inform OCR of any factual errors contained therein,” but give complainants no such opportunity.

“The new changes result in a lopsided system. Schools get more chances to show OCR they’re not discriminating, but complainants get no additional opportunities to show OCR evidence of discrimination,” said Seth Galanter, senior director for legal advocacy at the National Center for Youth Law and a former high-ranking official at OCR during the Obama administration. For staff, the update seemed like it came out of nowhere. When Jackson released the first CPM update of the administration in 2018, she sent proposed revisions to staff first, and then held an all-staff meeting to discuss them, a current attorney told HuffPost. Before the second update came out, management held a training session before publicly releasing it.

“What they chose to fiddle with and not mess with is always a little head scratching, especially when they’re not getting input on the ground,” said an attorney.

Marcus concedes that because the most recent CPM update was not as comprehensive as previous ones, outreach to staff might not have been as far reaching, although “we did reach out to all employees requesting suggestions,” he said.

The decision to give schools an opportunity to review draft investigatory findings was one “that had been requested by recipients, and some in the department simply felt was a basic matter of fairness or due process,” said Marcus. Allowing parents or students ― or the people who had filed the complaints ― the same opportunity “was not something that had been raised during the process. It certainly is, I think, something that could be raised with OCR in the future and probably could be considered.”

Other than their passion project of hurting trans kids, what else is the department or has the office done? Who are they helping?

Dwayne Bensing, former OCR attorney

In one of his final acts in February, Marcus moved to consolidate the agency’s employee-led Diversity and Inclusion and Employee Engagement Advisory councils, which worked with management to relay concerns and suggestions. The two committees were combined ― at the time Marcus told employees the consolidation would make them more strategic and comprehensive ― and membership was limited to representatives generally approved by regional management. After Marcus stepped down from his post in July, a new hire with a long history of vocal anti-transgender activism was one of the two employees appointed to head the committee over the summer, HuffPost reported in October.

“Diversity and inclusion remains a top priority for OCR’s leadership which is why the diversity and inclusion council is led by two senior leaders,” Morabito previously told HuffPost of the issue. The move, said former employees, seemed consistent with the agency’s lack of commitment to diversity under the Trump administration.

In September, the agency further withdrew from inclusion efforts when the White House issued an executive order banning federal agencies from participating in “divisive” racial and gender diversity training. In the Education Department, this meant rooting out diversity training that might discuss the concept of white privilege or suggest that “virtually all White people contribute to racism or benefit from racism,” Politico first reported.

At the same time, OCR attorneys previously told HuffPost they were under the impression they could still require school districts to root out bias at their own organizations through trainings, creating a specifically awkward conundrum. One attorney wondered how OCR attorneys could be expected to work with schools to root out discrimination, without being able to discuss such issues at their own agency. Morabito, however, has indicated that staff are no longer allowed to explicitly ask schools to conduct such trainings ― though multiple employees say this was never communicated to them. “OCR is unaware of any recent resolutions agreements that require or encourage school districts to use anti-bias training ― for the same reasons outlined in Executive Order 13950,” Morabito wrote to HuffPost.

The End Of An Era

The 2019 Office for Civil Rights annual report to Congress highlights some of the agency’s perceived accomplishments. Over the past two years, the office has resolved nearly 7,000 more complaints than had been resolved in the last two years of the Obama administration, the report says. This increase in efficiency is a major point of pride for the agency. Morabito also sent over numbers indicating it works through complaints more expeditiously than the previous administration, while being only slightly more likely to dismiss them.

“As each of OCR’s past two Annual Reports highlights, OCR has resolved complaints more effectively and more efficiently under the Trump Administration as compared to the Obama Administration,” wrote Morabito. “This is a stark contrast to OCR under the Obama administration, which often left students without resolution for years.”

A 2019 report from the United States Commission on Civil Rights, though, raises concerns about a “marked increase in case dismissal and closure rates in Fiscal Years 2017 and 2018” and questions whether the agency is meeting its duty “[to] investigate ‘whenever’ information indicates a possible failure to comply with the civil rights laws ED OCR enforces.” A 2018 ProPublica analysis found that the agency has become less likely to find school districts guilty of wrongdoing.

“I think the whole thing is insane, I think it is an OCR that under Betsy DeVos make up their own rules. The fact that they added all these additional ways for complaints to be dismissed … it’s so clear what an attack this is on the ability of Americans to file civil rights complaints,” said Lipsitt.

Looking to the future, current and former OCR attorneys say the Trump administration accomplished something that the Obama administration didn’t: It took more pains to codify its changes, making them more difficult for the Biden administration to roll back.

Attorneys also believe the reputation of the agency was harmed enough that they will have to do major outreach to get stakeholders to trust them to handle civil rights complaints again.

“It will be three more years to undo this,” said one former employee. “It was genius of them to do it this way. It will not be undone the day Biden takes office.”