Is it time to renew the 'nature versus nurture' debate? If so, can its beginning start with a discussion of keeping score by talking about 'smart people' and others....'For better or worse, rightfully or wrongfully, �intelligence� is the elephant in the classroom...'

No one will claim that Michael Jordan or Jahil Ochafor are not "gifted" as athletes specifically at least for playing basketball. And yet when it comes to discussing whether human children are endowed by virtue of birth with special talents for less visible activities -- music, art, math, language activities -- a kind of consensus has taken hold under which discussion of whether some people are "smarter" than others should be banned. And so Teachers College at Columbia University has issued a new study suggesting that we stop using the terms...

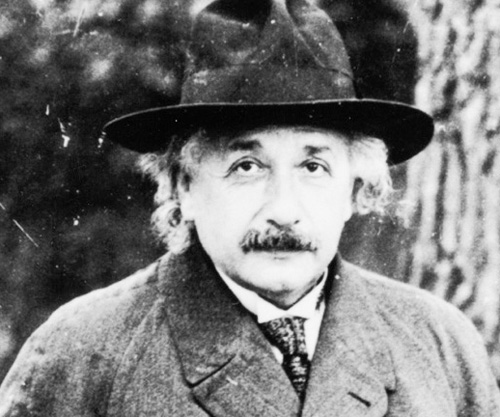

Albert Einstein at the time he published the General Theory of Relativity.Why Every Teacher, Parent, and Student Should Hate the Words �Intelligent� and �Smart� by Daniel LaSalle � Teachers College Press, February 16, 2015...

Albert Einstein at the time he published the General Theory of Relativity.Why Every Teacher, Parent, and Student Should Hate the Words �Intelligent� and �Smart� by Daniel LaSalle � Teachers College Press, February 16, 2015...

[Originally published by Teachers College Record, Date Published: February 16, 2015

http://www.tcrecord.org ID Number: 17865, Date Accessed: 2/20/2015].

Given psychologists' inability to reach a consensus on the appropriate definition of intelligence and the modest correlations between intelligence test scores and professional success, the author advocates for the potential benefits that could occur when teachers and schools drop the words intelligent and smart from classroom and school discourses.

For better or worse, rightfully or wrongfully, �intelligence� is the elephant in the classroom.

Sometimes it lives as the background noise in students� heads when they try to explain their academic successes or failures. Other times it takes center stage as teachers praise the performance of successful students or encourage the undermotivated by saying, �I know you are smart, but�� Despite the attention (direct or indirect) intelligence receives, academics are at odds to define it and research continually demonstrates modest to low correlations between intelligence test scores, professional success, personal fulfillment, and scores on other cognitive tests.

As educators, we are left with a very vexing question: If we do not know what �intelligence� means, and if it does very little to predict real-world success, should we use the word at all? I will argue no, and the more beneficial alternative is to treat each academic/cognitive strength and weakness as a separate issue in the classroom without ever mentioning the words �intelligent� or �smart.�

WHAT IS INTELLIGENCE?

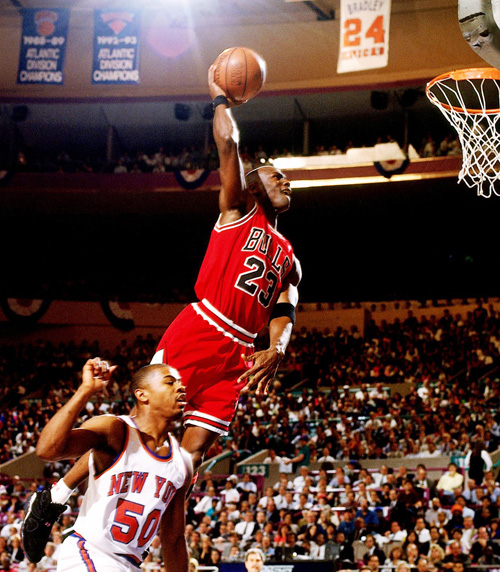

Michael Jordan in his prime.The question emerges, what do we mean by �intelligence?� This intensely debated issue divides researchers. The word �intelligence� existed long before we started measuring it (Sternberg, 2003). The word was not coined after its discovery, like �prefrontal cortex� or �amino acid,� so we cannot expect to define it and wash away all of the cultural and social associations attached to the word. Coming up with an agreed upon definition of intelligence, given how much weight it holds for people (whether they want to admit it or not), is like having scientists go back and redefine what it means to be a good �son� or �daughter.� You are bound to upset someone while, of course, raising suspicion of your credibility as an authority on the subject.

Michael Jordan in his prime.The question emerges, what do we mean by �intelligence?� This intensely debated issue divides researchers. The word �intelligence� existed long before we started measuring it (Sternberg, 2003). The word was not coined after its discovery, like �prefrontal cortex� or �amino acid,� so we cannot expect to define it and wash away all of the cultural and social associations attached to the word. Coming up with an agreed upon definition of intelligence, given how much weight it holds for people (whether they want to admit it or not), is like having scientists go back and redefine what it means to be a good �son� or �daughter.� You are bound to upset someone while, of course, raising suspicion of your credibility as an authority on the subject.

Surely social scientists have identified a pragmatic definition of intelligence�one that strongly predicts success on cognitive tests and correlates with success in the real world? The answer is no.

Scientists are at odds about which cognitive skills (and the accompanying psychometric tests) deserve the title �intelligence� (Neisser et al., 1996). What do we call a student who understands the complexity and subtlety of medieval literature but struggles to pass math class? What of the student who flawlessly solves math problems but is below grade level in reading and writing? How about the student who studies flashcards more than any other student at home and earns the highest grade on a vocabulary test? Certainly the reasons behind student achievement cannot always (or even often) be boiled down to a singular mental faculty we call intelligence.

IQ

The theory of intelligence that has arguably the greatest influence on school curricula and standardized tests is the Cattell/Horn/Carroll theory, which divides intelligence into two types: fluid and crystallized intelligence. It is commonly measured with the IQ test. Fluid intelligence (Gf) treats intelligence as a reasoning process and is measured by a slew of questions that involve analogies, series and matrices on the IQ test. Crystallized intelligence (Gc) treats intelligence as a matter of knowledge possession, and it is measured with vocabulary questions and similar matters of recall (having any flashbacks to the SATs?) (Stanovich, 2009).

The only problem is that the theories of fluid and crystallized intelligence, along with the IQ test, do not account for every cognitive strength a person could possess. Keith Stanovich (2009), a psychologist with expertise on intelligence tests, details these shortcomings. Correlations of less than .30 exist between measures of Gf and Gc with a person�s ability to consider alternate solutions and errors in a person�s own ideas, often called �open-minded thinking.� Moreover, there are almost zero correlations with highly valued character traits, such as diligence and curiosity.

Recently, the field of cognitive science has identified another subfield of decision-making processes called �rationality,� which is the likelihood a person will use normative problem-solution based thinking without falling victim to some very tempting heuristics and biases. Stanovich has shown a near zero correlation between successes at such thinking tasks and mid to high IQ levels.

For example, let�s say you decide to spend some of your paycheck playing roulette. The casino has kindly displayed the past winning numbers, �7, 38, 22, and 36.� You may reason that the roulette ball has not landed on the lower numbers for a while, and it will probably happen again soon. The problem is that the roulette ball lands on any number at random, without any care to what numbers it previously landed on. This faulty reasoning heuristic is called the �gambler�s fallacy� and represents one of dozens of irrational thinking tendencies that people with high IQs are only marginally less likely to engage in.

The limits of a singular definition and test for intelligence are probably not surprising. One probably does not have to think long before recalling a friend, family member, or student who thrives at chess but cannot seem to pass Algebra 1; bombs every chemistry test but can pick up another language in weeks; or writes beautiful poetry but cannot remember the multiplication tables.

BROAD THEORIES OF INTELLIGENCE

So maybe then the best view of intelligence is a broad theory of intelligence�one that defines intelligence as success at any thinking-related activity? In separate works, both Keith Stanovich (2009) and Daniel Willingham (2009) have articulated the problem with broad theories of intelligence. By expanding the definition of intelligences, we are left with little understanding of what it actually means to be better or worse at a given cognitive task. Some students unquestionably pick up certain skills faster and succeed more often than others. Willingham (2009) recognizes the appeal a broad theory of intelligence has for parents and teachers. Saying everyone is intelligent may sound like a great way to respect everyone�s own interests and talents, but it does not address those with specific and severe learning disabilities or help illuminate how or why students demonstrate differing degrees and rates of excellence at a given task. The second problem is that with such a general view of intelligence, what may appear as �being smart� is actually the result of hard work, patience, and curiosity.

MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES

What if we scaled back our definition a little? Having too specific a definition makes �intelligence� a club only a select few may enter when others may deserve to be invited. Having too broad a definition makes intelligence an open admissions institution whereby the word �intelligence� loses all practical and psychological utility. Maybe multiple intelligence theory is the solution.

Howard Gardner (2004), a psychologist at Harvard University, first proposed the idea of multiple intelligences. The theory postulates 9 specific intelligences: logical-mathematical, spatial, linguistic, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intra-personal, naturalistic, and existential. Although this theory certainly recognizes the diversity in academic achievements and those who reach them, the psychological community has spoken out against the deficiency in empirical evidence to suggest that multiple intelligences exist within this 9-tier framework (Willingham, 2009). Without sufficient research to demonstrate that nine different central processing abilities exist in human beings, the simpler explanation may simply be that �noncognitive factors,� the psychological phenomena not yet measured by cognitive tests, explain such academic success (Farrington et al., 2012). Such noncognitive factors could include interest, grit, resiliency, curiosity, and many others.

ABANDONING INTELLIGENCE

There is a disturbing pattern of scenarios I witness regularly in the lunchroom, hallways, and my classroom. It is the specter of intelligence that haunts students without them even knowing it. A student hardly studies for a quiz and aces it before proudly displaying the grade to her peers exclaiming, �I�m smart!� Another student whispers, �I�m dumb� while struggling on a test simply because he never finished the book for homework. I cannot help but worry about their malleable minds. They are crediting the causes of their success and struggles to something inherent to them, some almost omnipotent singular mental faculty. I worry if these students will leave school and enter the workforce believing a courtroom victory, successful medical diagnosis, or a great business pitch is due to being smart. I worry that the more they explain their behaviors with �intelligence,� the less they think their perseverance, resourcefulness, and ingenuity matters.

So what are teachers to do with a variety of limited definitions of intelligence with the full knowledge that intelligence is not what makes a life meaningful, beautiful, or even successful? The answer is simple. We do not use the word �intelligence� or �smart� in the classroom. No matter the delineation of �intelligence,� the better alternative is to celebrate the variety of factors that contribute to school success: grit, curiosity, open-mindedness, passion, memory, and so many more. Students, teachers, and the like could nurture the cognitive strengths and encourage the development of weaker ones without ever uttering the words �intelligence� or �smart� in a classroom. No student would be made to feel as the have or have-not by possessing the overly venerated Holy Grail we call �intelligence.� Even though multiple intelligence theory may not be valid, we can view the role of schools to nurture multiple �talents,� without this pressure-inducing and disempowering �smart� and �intelligent� words floating through conversations.

Academic success and motivation have been consistently linked to a student�s perception that they can succeed at the task (Deci, 1995). The more students credit their success or failure to their �intelligence,� or any singular thing, instead of embracing their perseverance, curiosity, or other virtues that are rightfully contributing to their academic performance, the more they unknowingly disempower themselves. Simply eliminating the words �smart� and �intelligence� from a school culture will certainly not automatically boost student achievement and motivation, but it is a first step.

References

Deci, E.L. & Flaste, R. (1995). Why We Do What We Do: Understanding Self-Motivation. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Farrington, C.A., Roderick, M., Allensworth, E.A., Nagaoka, J., Johnson, D.W., Keyes, T.S., & Beechum, N. (2012). Teaching Adolescents to Become Learners: The Role of Noncognitive Factors in Academic Performance�A Critical Literature Review. Chicago: Consortium on Chicago School Research.

Gardner, H. (2004). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Neisser, U., Boodoo, G., Bouchard T.J., Boykin A.W., Brody, N., Ceci S.J., Halpern D.F., Loehlin J.C., Perloff, R., Sternberg R.J., & Urbina, S. (1996). Intelligence: knowns and unknowns. American Psychologist, 51(2), 77�101.

Stanovich, K.E. (2009). What Intelligence Tests Miss: The Psychology of

Rational Thought. New Haven, CN: Yale UP.

Sternberg, R.J (2003). Wisdom, Creativity, and Intelligence Synthesized. New York, NY. Cambridge UP.

Willingham, D.T. (2006). Why Students Don�t Like School: A Cognitive Scientist

Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Comments:

By: Daniel LaSalle

My article

Hey Editors of Substance,

I'm just reading your response to my article now.

I saw our solution is to abandon using the words intelligence and smart in the classroom. You say that my suggestion is ridiculous.

My response: Why is this so hard to do? I've been teaching 5 years and I never use the word. I regularly attribute my students' successes to perseverance, motivation, interest, curiosity, and habit formation. Why is it ridiculous to omit the words intelligence and smart?

By: Sharon Schmidt

Don't use the word...

Interesting article, but ridiculous solution: "So what are teachers to do with a variety of limited definitions of intelligence with the full knowledge that intelligence is not what makes a life meaningful, beautiful, or even successful? The answer is simple. We do not use the word �intelligence� or �smart� in the classroom."

I wonder if Daniel LaSalle, the author of this simple article, realizes that excessive standardized testing and its resulting percentile rankings and bar graphs communicates this.