VALLAS WATCH, PART TWO: How the racist attack on African American teachers and principals was orchestrated and field tested in Chicago by Paul Vallas, Richard M.Daley, and a cast of hundreds -- launched behind a smokescreen of screaming about 'standards and accountability'

By the late 1990s, it was no longer a question of whether Paul G. Vallas was purging large numbers of African American teachers and principals from the ranks of Chicago's public schools, but how many would be slandered and destroyed and who would stand up to stop Vallas and the forces and ideology he represented. The case of principal Beverly Martin was just one of a dozen major examples, while hundreds of less prominent examples simply died in the fog of history that arises when those with wealth and power are not only doing the dirty work, but writing their narrative as the official version of history for future generations.

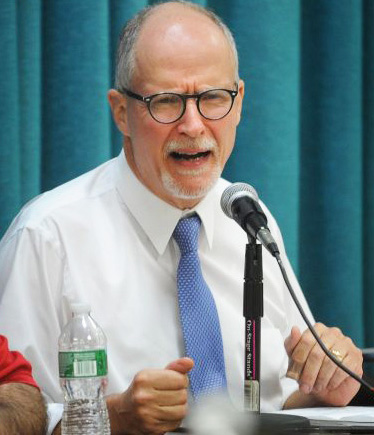

Just before he was rescued from public oblivion by Illinois Governor Pat Quinn, Paul G. Vallas was facing the end of his loud and controversial career in Connecticut. Above, Vallas was photographed at a Bridgeport Connecticut school board meeting by Connecticut Post during a heated controversy over the hiring of retired principals to run schools when schools needed the continuity of long-term commitments from principals and teachers. Vallas, who by the time he arrived in Connecticut in 2012, had established himself as a master of disruption and confusion, while continuing to reap the benefits of popular cultural myths that things like "disruption" were always good. Following the messy and racist results of Vallas's work as the "Chief Executive Officer" of the public schools of Chicago, Philadelphia, and New Orleans, Vallas's long record of frauds, many of them racist, had caught up with him in the simplest way. School leaders in Connecticut charged -- ultimately in court -- that Vallas was not certified to teach or be an administrator in Connecticut. Despite support from many of the state's most powerful people, Vallas was on the ropes -- until his career was saved when Illinois Governor Pat Quinn secretly informed Vallas that he would be Quinn's running mate. Photo courtesy of Connecticut Post.From the beginning, any so-called "school reform" program that pretended to measure school, teacher, principal and child success by means of so-called "standardized" tests was bound, at least in most major American cities, to be racist. The reason was as simple as the IQ tests that began the movement of such things: Virtually all of the tests, once they had been "normed" according to psychometric "science," were going to prove that poor black kids were "failing." As a result, once the public narrative was locked into a fetishization of test scores, anything could be done by those with economic and political power to those who had less or none. "Failing" children could be forced to repeat grades or attend mindless test prep summer schools. "Failing" children's families could be made to feel that if they only worked harder they could "raise" their scores. And the teachers and principals who worked in schools filled with "failing" children could be fired.

Just before he was rescued from public oblivion by Illinois Governor Pat Quinn, Paul G. Vallas was facing the end of his loud and controversial career in Connecticut. Above, Vallas was photographed at a Bridgeport Connecticut school board meeting by Connecticut Post during a heated controversy over the hiring of retired principals to run schools when schools needed the continuity of long-term commitments from principals and teachers. Vallas, who by the time he arrived in Connecticut in 2012, had established himself as a master of disruption and confusion, while continuing to reap the benefits of popular cultural myths that things like "disruption" were always good. Following the messy and racist results of Vallas's work as the "Chief Executive Officer" of the public schools of Chicago, Philadelphia, and New Orleans, Vallas's long record of frauds, many of them racist, had caught up with him in the simplest way. School leaders in Connecticut charged -- ultimately in court -- that Vallas was not certified to teach or be an administrator in Connecticut. Despite support from many of the state's most powerful people, Vallas was on the ropes -- until his career was saved when Illinois Governor Pat Quinn secretly informed Vallas that he would be Quinn's running mate. Photo courtesy of Connecticut Post.From the beginning, any so-called "school reform" program that pretended to measure school, teacher, principal and child success by means of so-called "standardized" tests was bound, at least in most major American cities, to be racist. The reason was as simple as the IQ tests that began the movement of such things: Virtually all of the tests, once they had been "normed" according to psychometric "science," were going to prove that poor black kids were "failing." As a result, once the public narrative was locked into a fetishization of test scores, anything could be done by those with economic and political power to those who had less or none. "Failing" children could be forced to repeat grades or attend mindless test prep summer schools. "Failing" children's families could be made to feel that if they only worked harder they could "raise" their scores. And the teachers and principals who worked in schools filled with "failing" children could be fired.

What was important was to sustain the narrative that said it was not only possible but politically correct to rank and sort children, teachers, principals and schools by means of some so-called "standardized" tests. It didn't matter what the tests were. The key was to dominate the public narrative. And so, from the beginning in 1995, Paul Vallas shifted tests around, confident that reporters would be mesrmerized by the ranking and sorting part and ignore the underlying racism and craziness. In the first three years of the Vallas administration, it was the ITBS and TAP, followed by the IGAP) that were utilized. During the same years, Vallas got millions of dollars to create local tests with similar objectives (the CASE, Chicago Academic Standards Examinations, which Substance exposed as frauds). Vallas during those years worked overtime and with relentless energy to dominate the narrative, often with the help of lazy or corrupt news people like the pundit for the Chicago Sun-Times, Raymond Coffey. The key was to create and announce the all-important lists. From the beginning, Vallas's lists should have been ignored -- or satirized like a Cosmopolitan magazine cover touting the "Ten Best Ways to Reach Your Peak Orgasm." But the fetishes of American popular culture were (and still are) being manipulated by Paul Vallas and other corporate reformers, usually through some American journalistic nonsense. Those in charge (CEOs like Paul Vallas and Richard M. Daley) were inaugurating a new era of "No Excuses" and high standards for everybody. As long as they could control the narrative (and libel and slander their critics, which includes this reporter and Substance), they got away with it.

The launching of two decades of scapegoating of inner city teachers and principals that resulted, first in Chicago and eventually in most major cities, in the destruction of inner city public schools, the greatest reduction in the number of African American teachers and school administrators in history, and the replacement through privatization of first dozens, then hundreds, and now thousands of real public schools by a growing local, then national movement of charter schools. And for most of the two decades since Chicago launched this stuff under Paul G. Vallas and Richard M. Daley, the attacks worked.

One of the most interesting, complex, and lengthy examples of the Vallas method came during the battles over the principalship of Gale Elementary School, on the far far northeast side of Chicago. Rather than simply share Substance reporting on this one, here is a summary of the Gale school battles over whether Beverly Martin should be principal from Catalyst. The very public and acrimonious battles over what became "The Beverly Martin Case" provided anyone who was paying attention to the "Paul Vallas Method" with a set piece study of the racism, opportunism, media manipulation, and outright dishonesty of the ways in which Paul Vallas operated during his years in charge of Chicago's schools. Note, however, below that the Beverly Martin story began in 1997.

The year 1997 was when Vallas was at the height of his power and influence (that was the first year that the President of the United States, Bill Clinton, actually cited the "Chicago Miracle" in the State of the Union Address; as the facts came out over the next couple of years, Clinton gave Chicago one more State of the Union hug and then stopped talking about Chicago's "education reform," for more and more obvious reasons). Throughout the Gale School saga, a singular fact was that Beverly Martin is African American, and after the final resolution of the sage (the settlement in a federal civil rights lawsuit filed by Beverly Martin), the "Beverly Martin Case" joined a number of others, some of which were adjudicated in federal court and others of which were local scandals, as examples of the virulent racism of the administration of Chicago's first public schools "Chief Executive Officer."

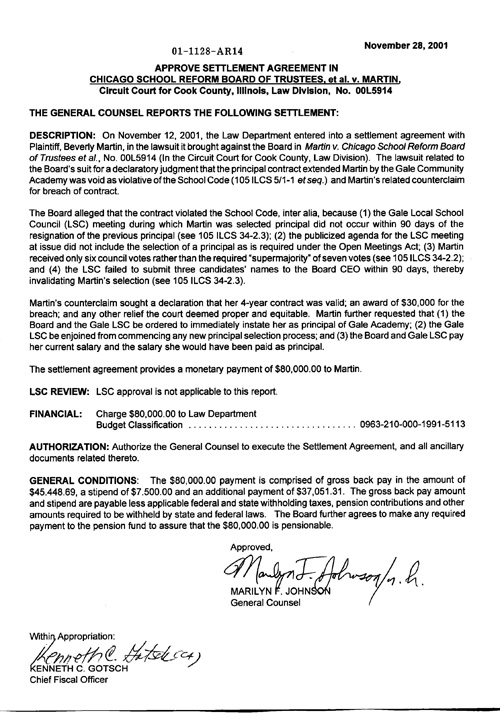

Five months after Paul Vallas was ousted as CEO of CPS, the Board of Education, on November 28, 2001, voted to settle the Beverly Martin case regarding the principalship of Gale Elementary School. The Martin case, unlike several of the cases that showed the racism of Paul Vallas's relationship to African American principals and administrators, was a contract case, not a civil rights case. In subsequent settlements, the Board also paid the attorneys' fees for all three lawyers who had been working the case: Martin's lawyers; the Board's lawyers; and the lawyers representing the Gale LSC. By November 28, 2001, the Board of Education was again voting on a settlement of a lawsuit that basically demonstrated the racist policies of Paul Vallas. Beverly Martin had filed her lawsuit in local court because she was arguing that she was legally entitled to the job as principal of Gale School which the Local School Council had voted on in 1997. Martin continued to work for CPS during the four years that the litigations proceeded, so her monetary damages were low. But as the Board of Education quietly moved to clean up the legal messes left behind by the Vallas years and the Vallas legacy of racism, the Beverly Martin case was settled. In each of the cases, federal or local, the settlements meant that the Board didn't have to face a public trial in open court. [As we will report later in this series, one of the most complex of those cases involved a lawsuit filed by Vallas against Substance and this reporter charging $1.4 million in damages because Substance published the ridiculous CASE tests. In that case, because I insisted on our Seventh Amendment rights to a jury trial on the damages, a U.S. district magistrate judge urged the Board in 2003 to reduce their damages claim (which had already been reduced to $700) to zero Under the Seventh Amendment were had the right to a jury trial if the civil suit could result in damages against me (and Substance) of $50 or more. Once the Board went down from the original $1.4 million to zero, the possibility of a public jury trial proving the waste of money by Vallas on the CASE tests was over].

Five months after Paul Vallas was ousted as CEO of CPS, the Board of Education, on November 28, 2001, voted to settle the Beverly Martin case regarding the principalship of Gale Elementary School. The Martin case, unlike several of the cases that showed the racism of Paul Vallas's relationship to African American principals and administrators, was a contract case, not a civil rights case. In subsequent settlements, the Board also paid the attorneys' fees for all three lawyers who had been working the case: Martin's lawyers; the Board's lawyers; and the lawyers representing the Gale LSC. By November 28, 2001, the Board of Education was again voting on a settlement of a lawsuit that basically demonstrated the racist policies of Paul Vallas. Beverly Martin had filed her lawsuit in local court because she was arguing that she was legally entitled to the job as principal of Gale School which the Local School Council had voted on in 1997. Martin continued to work for CPS during the four years that the litigations proceeded, so her monetary damages were low. But as the Board of Education quietly moved to clean up the legal messes left behind by the Vallas years and the Vallas legacy of racism, the Beverly Martin case was settled. In each of the cases, federal or local, the settlements meant that the Board didn't have to face a public trial in open court. [As we will report later in this series, one of the most complex of those cases involved a lawsuit filed by Vallas against Substance and this reporter charging $1.4 million in damages because Substance published the ridiculous CASE tests. In that case, because I insisted on our Seventh Amendment rights to a jury trial on the damages, a U.S. district magistrate judge urged the Board in 2003 to reduce their damages claim (which had already been reduced to $700) to zero Under the Seventh Amendment were had the right to a jury trial if the civil suit could result in damages against me (and Substance) of $50 or more. Once the Board went down from the original $1.4 million to zero, the possibility of a public jury trial proving the waste of money by Vallas on the CASE tests was over].

CATALYST COVERAGE OF THE BEVERLY MARTIN STORY FROM 1997 THROUGH 2002:

CATALYST ON THE GALE SCHOOL AND VALLAS STORY...

THE PROCESS

On April 21, the Gale council votes 7 to 2 to offer a principal's contract to Beverly Martin, a central office administrator. The Law Department later declares the vote null and void due to alleged irregularities regarding the meeting's posted agenda. The council majority disputes the ruling but agrees to vote again, which it does in late June. This time, the vote for Martin is 6 to 3.

By: Dan Weissmann / September 1, 1997

From the September, 1997 issue of Catalyst-Chicago Local School Councils

As Catalyst goes to press, a showdown is imminent at Gale Community Academy, where controversy has racked the local school council for more than a year. Chief Executive Officer Paul Vallas has announced his intention to have the school declared in "educational crisis" so he can clean house. Backed by school reform groups and the Chicago Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, a majority of Gale's LSC members are preparing to file a lawsuit against the board, charging that Vallas is usurping the LSC's power to name a principal. Here's the background.

THE PROCESS On April 21, the Gale council votes 7 to 2 to offer a principal's contract to Beverly Martin, a central office administrator. The Law Department later declares the vote null and void due to alleged irregularities regarding the meeting's posted agenda. The council majority disputes the ruling but agrees to vote again, which it does in late June. This time, the vote for Martin is 6 to 3.

At this point in the principal selection process, state law requires a 7-vote majority. Councils that can't muster 7 votes are required to submit three names, in rank order, to the chief executive officer, who has 30 days to choose one. If he doesn't, the council then needs only 6 votes to choose one of the three candidates.

Vallas rejects all three of the Gale council's candidates. So, on July 28, the council again votes 6 to 3 for Martin. Vallas has said the Gale council still must gather 7 votes to select a candidate, but the Law Department is not backing him up. Asked her legal opinion, chief attorney Marilyn Johnson told CATALYST: "I do not care to say. I know that is the burning question of the hour, and that I will not say."

In early August, the Office of School and Community Relations sends a letter to all Gale council members, telling them they're being investigated. The council majority responds with a public relations campaign aimed at getting Vallas to accept Martin.

In mid-August, Vallas tells the Chicago Tribune that he hopes to remove members of the council by declaring an "educational crisis" at Gale. According to board officials, that means Martin will not become principal. A lawyer for the council majority maintains otherwise, saying a vote taken by a legally constituted body cannot be overturned by a subsequent change in member composition.

THE POLITICS AT GALE Long-simmering tensions among competing groups of parent and community leaders and Gale's administration erupted into a full boil during campaigning for Gale's 1996 local school council elections: An all-Latino slate of candidates challenged an all-black slate that dominated the council and was allied with the school's white principal.

The Latino faction pulled an upset victory, winning a majority of seats on the council. Before, during and after the election, accusations ranging from racism and anti-Semitism�the then- principal and many Gale teachers are Jewish�to electioneering and vote fraud flew back and forth. The School Board investigated the vote-fraud charges and ultimately gave the elections a clean bill of health.

The council then settled in to several months of bickering between the Latino majority and the black minority, with School Board officials often on hand to mediate.

Then, in December 1996, the school's veteran principal left to take a job at School Board headquarters, and Vallas appointed an interim, Guadalupe Shields, fresh from the University of Chicago's Center for School Improvement and a former principal of Plamondon Elementary.

The opportunity to select a new permanent principal triggered a re-alignment on the council; black and Latino members started working together to take advantage of the chance to pick an administrator. For a while, things went relatively smoothly. The council created a selection committee that included parents, community members and teachers; and the committee set criteria for potential candidates.

Shields was eliminated from the running early on because she narrowly missed meeting one of the criteria: five years of elementary school teaching experience. "That's when the controversy started," says James Deanes of the Office of School and Community Relations, who frequently attended Gale LSC meetings.

Some teachers were upset that Shields was eliminated out-of-hand, but Deanes takes the council's side on this issue. "Once you set criteria, that's a process that ought to be followed," he says.

Teacher unrest escalated when an anonymous, anti-Semitic note was posted in the teachers lounge. The unrest spread when the incident became fodder for Chicago Sun-Times columnist Ray Coffey, who tied the note to the Gale council's refusal to consider Shields for the principal's position. (A board investigator later determined that the note had been posted by an un-aligned agitator on the Gale faculty.)

Citing Vallas as his source, Coffey blamed Gale's troubles on local activist Carlos Malave. Though Malave was a member of Gale's principal selection committee, Coffey called him a "political carpetbagger" who "has no official role at Gale."

At the April 21 council meeting, parent LSC member Virginia Aviles and teacher Dennis Gallagher voted against Martin; both had shared fellow council members' dissatisfaction with the previous principal. Gallagher's primary objection was that Martin had not worked in an elementary school since 1976. Aviles, Gallagher and Deanes, who was an observer, contend that the council majority conspired to ram through Martin's selection. Convinced that the process was being hijacked, Aviles brought her concerns to Vallas and Coffey, who took up her cause.

Since then, it has been a free-for-all. Here's a sampling of events and accusations:

In May, a member of the council majority puts out a flyer denouncing Aviles, Gallagher, Coffey and Vallas for brewing up a racist conspiracy against the LSC's majority. He alleges that Aviles and Gallagher oppose Martin's appointment because Martin is black. Gallagher counters that all of the finalists were people of color, and that his choice was another black woman.

An African-American member of the majority, Wayne Frazier, tells a reporter from the News-Star, a neighborhood weekly, that Gale teachers are "fighting [the council] tooth and nail" over Martin's prospective appointment. "The teachers are saying she's going to come and fire all the Jewish teachers and bring in all minorities," he says.

At a late June School Board meeting, Aviles asks Board President Gery Chico to keep the school reform groups Parents United for Responsible Education and the Lawyers School Reform Advisory Project away from the Gale LSC. "They are wolves!" she says. (Aviles's nemesis, Frazier, sits on PURE's board of directors.)

On August 13, the News-Star publishes a letter from PURE director Julie Woestehoff, who calls the newly opened School Board investigation a "witch hunt." Woestehoff helps council members organize a demonstration outside the school a week later.

Board officials confront Dennis Weekly, a member of the LSC majority, alleging that he failed to properly disclose a past conviction on a drug-related offense. Weekly says he believes that he did disclose the offense because his past is no secret; he works with anti-drug groups, telling kids not to repeat his mistakes. He says he is upset that the board would stoop to intimidation. Deputy Chief Education Officer Carlos Azcoitia explains that the board must make sure that all council members follow the law. When an investigation is underway, "we take a look at all of these aspects."

In mid-August, Vallas announces his intention to declare a crisis at Gale and dissolve the LSC. "I'm not going to stand by while the leadership of that school is usurped by outsiders," he tells the Chicago Tribune. "This is about power, ego, patronage."

THE POLITICS OF REFORM To Julie Woestehoff, director of Parents United for Responsible Education, the Gale dispute is about Vallas's power, ego and patronage. "In my opinion, this is simply a temper tantrum from someone who wants to control the principal selection process and isn't being allowed to do it. I think that Vallas wants to appoint principals to schools; he wants to control that person."

For Woestehoff and other council advocates, Gale has become a test case for a primary tenet of school reform: The law gave LSCs the responsibility for selecting principals so that principals would be accountable to local communities.

For Amy Zimmerman of the Chicago Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Gale has become a legal test case, too. "Every LSC out there should be quaking in their boots over this case." At press time, the Lawyers' Committee was deciding whether to file a lawsuit.

Deanes calls the power-grab accusation "a blatant lie." Rather, he says, the council's allies are distorting the truth in order "to embarrass the [Vallas] administration as being anti-local-school-council."

According to Deanes, the fundamental issue is: "Do we have people who are fighting for kids, or do we have people who are just fighting?" From his perspective, "Any group that does not promote harmony among LSCs is suspect. ... That does not mean you're kow-towing to central office; it just means that kids are entitled to an atmosphere where things are discussed calmly." If the board has to take a firm hand to get that accomplished, Deanes says, so be it.

Even so, he does not absolve the board of responsibility for the mess at Gale. "All of us shoulder that responsibility," he says, citing the board, council members and various activist groups. "Everybody should leave with their plate full; there is enough for everybody."

ONLINE UPDATE: School Board seeks court opinion on principal selection, places Gale on remediation

On August 27, the School Reform Board voted to ask a judge to clarify the law on principal selection. At issue is whether the Gale Community Academy Local School Council needs 6 or 7 votes to choose a principal after having had three of its recommendations rejected by Chief Executive Officer Paul Vallas.

"We believe there is enough of a gap, or silence, from the statutes that warrants a ruling from the court," explained Board President Gery Chico.

Meanwhile, school officials backed off declaring Gale in educational crisis, which Vallas had sought as a way to remove LSC members. Instead, the board voted to place Gale on remediation, a designation that, unlike educational crisis, does not require a public hearing.

Vallas told reporters the move was warranted by "an academic free fall" at the school. Speaking to the Chicago Sun-Times through an interpreter, the council president called it "unjust," adding, "But this is something that is not over."

The decision to place Gale on remediation is a departure from past practice. For one, the current principal, who is serving in an interim capacity, was selected by Vallas last December. Also, most of the 37 elementary schools that were on remediation last school year had around 15 percent of their students score at or above national norms in reading on the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills. Gale has 22.6 percent at or above average, a slight increase from 1996. Since 1993, Gale's scores on the state IGAP tests have fluctuated.

While the board moved several schools from remediation to probation, Gale is the only school it added to the remediation list.

Debra Williams

Links to other stories about Gale:

April, 1995: Year-round school 'the best thing since Wonder Bread'

September 1995: Vallas & Co. respond to school in turmoil

October, 1995: Dual shifts out�along with a few jobs

December, 1995: Gage welcomes Sylvan; Gale glimpses crowding relief

June, 1996: Latinos score upset victory after year of litigation

September, 1996: Victors in Gale election turn back legal challenge

Link to recent columns by Ray Coffey of the Sun-Times, who frequently writes about Gale.

For links to Lerner newspaper stories on Gale, see:

May 7, 1997: Gale buffeted by accusations, ethnic politics

July 16, 1997: Gale's interim principal outlines changes made for new school year

August 6, 1997: Gale storm clouds gathering

August 20, 1997: Vallas to challenge Gale school council

For demographic and test score information about Gale, go to the Chicago Public Schools Information Database and select Gale from the scrolling menu.

Comments:

By: Joe Kenny

Vallas is all about Vallas...

Vallas has been the wolf in sheep's clothing forever. He plays the game pretty well, but if you look at the FACTS and not his words, we see that Vallas is all about Vallas. He knows where his bread is buttered. He does the bidding of the corporations 24/7.

By: Bob Busch

Chainsaw Paul

There were some principals he could not intimidate.The principal at Hubbard told him to go to hell,using educational terms.

Simeon was too tough a nut for even him to crack.And Bogan just kept smiling and went on it's merry way.

I am sure other principals did not take his bullshit,but those are the three I know about.