Obama has more in common with James Buchanan than with Abraham Lincoln... Founding of the Republican Party worth noting on anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation... Third Party not always a bad idea in U.S. history

Introductory Note: The 150th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation is an invitation to consider where we are today, 150 years rid of Southern slavery, but now shackled to senile capitalism, assorted tumors such as right-to-work laws, and threats to the institution of public education. In this sesquicentennial, there are some interesting comparisons with mid-19th century U.S. and Cyberspace America 2013. A recent Substance News article ['Fiscal Cliff' nonsense shows again that Obama is no 'Lincoln'…] compares Obama's compromises with financial capital to James Buchanan's (President from 1857-1861) compromises with slavery, to "save" the union. George Schmidt in the article notes "history does not necessarily judge those who favored 'compromise' favorably when the light of subsequent events shines upon them."

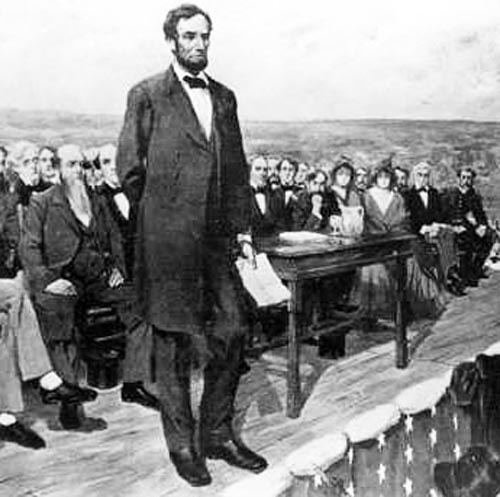

Above, one depiction of Abraham Lincoln delivering the Gettysburg Address in 1863. Lincoln was one of the founders of the Republican Party, which was begun in Illinois following the frustration of those opposed to the expansion of slavery with the existing parties.I'd like to continue that line of thinking. The irreconcilable differences in antebellum America gave rise to the Republican Party, a new party, which did not miraculously fall from the sky. It evolved, in fragmentary steps, out of a complex process born from a compromise that could not be made. The recently released film "Lincoln" is a wonderfully-crafted addition to the Lincoln hagiography. But I ask the reader to look away for a moment from the 'history viewed through the lens of personalities' approach. I invite instead that newly spawned political party of yore (Republican) to take center stage. Is there some lesson in it for us, as we battle with similar, hopelessly doomed compromises: shall we toil in serfdom to Wall Street, or, united, take control of our collective destiny?

Above, one depiction of Abraham Lincoln delivering the Gettysburg Address in 1863. Lincoln was one of the founders of the Republican Party, which was begun in Illinois following the frustration of those opposed to the expansion of slavery with the existing parties.I'd like to continue that line of thinking. The irreconcilable differences in antebellum America gave rise to the Republican Party, a new party, which did not miraculously fall from the sky. It evolved, in fragmentary steps, out of a complex process born from a compromise that could not be made. The recently released film "Lincoln" is a wonderfully-crafted addition to the Lincoln hagiography. But I ask the reader to look away for a moment from the 'history viewed through the lens of personalities' approach. I invite instead that newly spawned political party of yore (Republican) to take center stage. Is there some lesson in it for us, as we battle with similar, hopelessly doomed compromises: shall we toil in serfdom to Wall Street, or, united, take control of our collective destiny?

The First Successful Third Party and the Civil War by Larry Duncan

It was the great turning point in U.S. history, when neither of the two major parties could clearly express the new, inexorable movement against slavery. A third party grew rapidly out of this crisis, a new party that was not simply a repackaging of the Whigs. It was the Republican Party in the 1850s.

The sudden appearance of the Republican Party in the decade preceding the outbreak of Civil War has been dismissed as (1) merely a retread of the old Whig party and therefore not a new, third party; and (2) an insignificant phenomenon in itself that is merely a backdrop to the fabled Lincoln.

These misconceptions contributed to the seriously mistaken opinion that there has never been a successful major third party in U.S. elections.

As the western territories began to open up at mid-century, the nation east of the Mississippi was drawn into a debate about what system of labor (free or slave) would exist in the newly forming states. The small family farmers and free laborers of the North as well as the slave-owning plantation bosses of the South each thought Horace Greely was speaking exclusively to them when he said: “Go West, Young Man!”

One of the leading abolitionists in Illinois during the first half of the 19th Century was Elijah Lovejoy, a minister and printer from Alton. Elijah Lovejoy was murdered defending his abolitionist press from a pro-slavery attack in 1837. His brother Owen became a founding leader of the Republican Party and served in Congress during the Civil War.Although anti-slavery sentiment had always existed even in the prerevolutionary colonies, serious attempts at creating political parties that addressed the slavery problem began appearing in the 1840s. The 1844 platform of the Liberty Party (a small, marginal party) had as its key demand the ending of any government sanction of slavery.

One of the leading abolitionists in Illinois during the first half of the 19th Century was Elijah Lovejoy, a minister and printer from Alton. Elijah Lovejoy was murdered defending his abolitionist press from a pro-slavery attack in 1837. His brother Owen became a founding leader of the Republican Party and served in Congress during the Civil War.Although anti-slavery sentiment had always existed even in the prerevolutionary colonies, serious attempts at creating political parties that addressed the slavery problem began appearing in the 1840s. The 1844 platform of the Liberty Party (a small, marginal party) had as its key demand the ending of any government sanction of slavery.

By 1848, distinct anti-slavery and pro-slavery factions had grown in both the Whigs and Democrats. Both of these two major national parties sought (unsuccessfully ultimately) to sublimate these fundamentally irreconcilable views within their organizations. This internal conflict led the Whig Party (the party of Daniel Webster and Henry Clay) to complete annihilation in the 1850s, and it led the Democratic Party to an ignominious defeat in 1860.

The 1848 Democratic Party’s convention platform took no firm stand on whether the new territories ought to be slave or free, and it denounced the radical abolitionists. The Democratic Party that election year distributed two versions of campaign literature: one for the North and another for the South. This evasiveness enraged the antislavery faction (The Barnburners), who began to look for allies outside their party. The Barnburners got their name from the story of the farmer who burned down his barn to get rid of the rats living in it. Thus, the Barnburners chose to destroy the Democratic Party to get rid of the pro-slavers inhabiting it.

Meanwhile, inside the Whig Party, the Conscience Whig faction opposed their party’s nominating a Louisiana slave holder for president.

The Conscience Whigs united with the Barnburner Democrats and the remnants of the 1844 Liberty Party to form the Free Soil Party, which met in convention and adopted the slogan “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor and Free Men.”

The Free Soil Party in 1848 went on to win 14% of the vote in the non-slave (free) states, and actually outdid the Democrats in Massachusetts, Vermont and New York, where it won 43% of the vote! In that election the Whig’s candidate, Zachary Taylor, won the Presidency against the Democrats’ Lewis Cass. (Neither of these parties were seen as distinctly regional, though the Whigs were somewhat stronger in New England than elsewhere.)

The writing was clearly on the wall that the anti-slavery issue, in all its permutations, was a sufficient enough cause by which a new party could be formed. And the corollary: a new party would have to be formed to take forward the anti-slavery issue.

One of the ironies of Chicago public school history of the late 20th and early 21st Century has been the denigration of public schools by the city's plutocratic elite and some in the city's ruling political class. Even before Chicago became a noisome model for the privatization of public schools across the USA, privatization of school property for the benefit of politically connected real estate owners was becoming a major scandal. The public school named after the Civil War general George Thomas, for example, was sold to a condominium developer and is now the "Schoolhouse Condos" although Thomas's name can still be read in the building's stonework.The movement against slavery had several variations. On one end of the spectrum were those who simply wanted to coexist with it in the states east of the Mississippi and stop its growth in the new states. Others wanted to limit slavery to only half of the new territories, such as what was agreed to in the Missouri Compromise. On the left end of the scale were the radical abolitionists, who were not prepared to endure slavery anywhere at any time. There were those who abhorred slavery for moral and humanitarian reasons. Others opposed its contaminating the West because it interfered with their economic objectives there.

One of the ironies of Chicago public school history of the late 20th and early 21st Century has been the denigration of public schools by the city's plutocratic elite and some in the city's ruling political class. Even before Chicago became a noisome model for the privatization of public schools across the USA, privatization of school property for the benefit of politically connected real estate owners was becoming a major scandal. The public school named after the Civil War general George Thomas, for example, was sold to a condominium developer and is now the "Schoolhouse Condos" although Thomas's name can still be read in the building's stonework.The movement against slavery had several variations. On one end of the spectrum were those who simply wanted to coexist with it in the states east of the Mississippi and stop its growth in the new states. Others wanted to limit slavery to only half of the new territories, such as what was agreed to in the Missouri Compromise. On the left end of the scale were the radical abolitionists, who were not prepared to endure slavery anywhere at any time. There were those who abhorred slavery for moral and humanitarian reasons. Others opposed its contaminating the West because it interfered with their economic objectives there.

In the late 40s the National Reform Association was created by labor leaders in the West to oppose the sale of public lands to raise federal revenues. The Association supported instead homestead legislation reform so that free laborers could be given Western land to farm. This increased their bargaining power with their Eastern factory employers, who would have to keep their wages higher The First Successful Third Party and the Civil War by Larry Duncan to entice them to not head west.

The Association organized a series of Industrial Congresses, which formed a natural partnership with western farmers, who needed free land in the territories once their own land was farmed out. The remnants of the National Reform Association, bringing together “farmers, mechanics, and other useful classes” became one of the components of the Republican Party when it finally emerged in 1854-60.

Although the Whigs and Democrats hoped that third party movements would subside after the 1852 election, in 1854 Senator Stephen Douglas proposed to repeal the Missouri Compromise (no slavery north of that state) in the Kansas-Nebraska Act. This detonated an explosion.

A great political uproar arose in the North, and the first targets were Northern Democrats who supported the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. Their Whiggish cothinkers were all primarily in the South; thus Northern Whigs were identified with pro-Missouri Compromise, anti-Nebraska [the Kansas-Nebraska Act] sentiment. Northeastern Whigs, however, sought to avoid fusing with anti-Nebraska movements and still held the hope along with their Southern Whig comrades that the slavery question would remain a secondary issue in national politics. But in the Northwest, the Whigs were weaker and were enticed out of their party into the new, anti-Nebraska party formations.

In Ripon, Wisconsin, an anti-Nebraska meeting on March 29, 1854, suggested a new name: the Republican Party. On July 26, anti-Nebraskaites in Michigan held a formal convention and officially declared themselves the Republican Party.

Chicago was the scene of the nomination of Abraham Lincoln as the candidate of the Republican Party in the 1860 election and was a center of northern support for the union, both during and after the Civil War. Northern abolitionist leaders like Carl Schurz (above in a 1906 photograph) were prominent heroes in Chicago, which named public schools after dozens of Union leaders from the Civil War and prided itself on the fact that no Chicago public school was ever named after a Confederate leader. (The Davis and Lee elementary schools, for example, are not named after Jefferson Davis or Robert E. Lee). Carl Schurz High School on Chicago's northwest side is one of the greatest surviving monuments to the linkage between Civil War abolitionism and full public education. In Illinois, an anti-Nebraska convention (referred to in a letter by Lincoln as the “Republican Party”) met in Springfield on October 4, 1854, at the statehouse during the Illinois state fair. Billed as a “mass convention,” it fell a little short of that, with some 26 persons attending, including Abraham Lincoln and Owen Lovejoy (the abolitionist brother of the martyred publisher Elijah). Although the platform did not oppose the fugitive slave law nor the existence of slavery where it was already established, it did oppose its extension. The convention failed to create a permanent organization, and the state central committee never got around to serving.

Chicago was the scene of the nomination of Abraham Lincoln as the candidate of the Republican Party in the 1860 election and was a center of northern support for the union, both during and after the Civil War. Northern abolitionist leaders like Carl Schurz (above in a 1906 photograph) were prominent heroes in Chicago, which named public schools after dozens of Union leaders from the Civil War and prided itself on the fact that no Chicago public school was ever named after a Confederate leader. (The Davis and Lee elementary schools, for example, are not named after Jefferson Davis or Robert E. Lee). Carl Schurz High School on Chicago's northwest side is one of the greatest surviving monuments to the linkage between Civil War abolitionism and full public education. In Illinois, an anti-Nebraska convention (referred to in a letter by Lincoln as the “Republican Party”) met in Springfield on October 4, 1854, at the statehouse during the Illinois state fair. Billed as a “mass convention,” it fell a little short of that, with some 26 persons attending, including Abraham Lincoln and Owen Lovejoy (the abolitionist brother of the martyred publisher Elijah). Although the platform did not oppose the fugitive slave law nor the existence of slavery where it was already established, it did oppose its extension. The convention failed to create a permanent organization, and the state central committee never got around to serving.

The 1854 Congressional elections experienced a surge of new parties and party fragments: there were Democrats, Whigs, Free Soilers, Republicans, People’s Party, Fusionists, Know-Nothings (against foreigners and Catholics), Hard Shell Democrats, Soft Shells, Half Shells. One historian counted 18 different parties.

The editors of the Congressional Record in 1855 ceased identifying speakers by their party backing, so complex was their provenance. There were those who got elected with antislavery and nativist (anti-immigrant) support; with pro-slavery and nativist support; with anti-slavery and nonnativist backing; with anti-Nebraska plus anti-slavery support; and with Know-Nothing support. Within this political farrago, the Republicans prevailed as the polar attraction for the major Third Party.

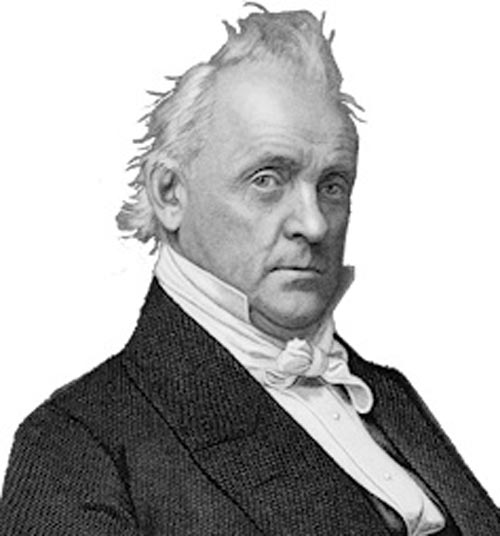

James Buchanan was President of the United States during the months after the election of Abraham Lincoln (in November 1860) and Lincoln's inauguration (March 1861). Buchanan's initial opposition to slavey had become muted by the time he was the Democratic Party's candidate for President of the United States in 1856. Buchanan's final compromises took place as the states that became the Confederate States of American seceded from the United States prior to Lincoln's inauguration. In the opinion of a growing number of historical observers, Barack Obama is no Lincoln and Obama's compromises put him more in the historical tradition of Lincoln's immediate predecessor, Buchanan. By 1856, these regionally tentative beginnings of 1854 had congealed into a movement strong enough to hold a national convention and field a presidential candidate — John C. Fremont, who won 33% of the popular vote. The Democrats (and Buchanan) got 45%, and Know- Nothings (nativists) got 22%. The Whigs were finished. And within the Know-Nothings, north-south factionalism started to develop. It was simply a matter for the Republicans to hold together for another four years, for the 1860 election.

James Buchanan was President of the United States during the months after the election of Abraham Lincoln (in November 1860) and Lincoln's inauguration (March 1861). Buchanan's initial opposition to slavey had become muted by the time he was the Democratic Party's candidate for President of the United States in 1856. Buchanan's final compromises took place as the states that became the Confederate States of American seceded from the United States prior to Lincoln's inauguration. In the opinion of a growing number of historical observers, Barack Obama is no Lincoln and Obama's compromises put him more in the historical tradition of Lincoln's immediate predecessor, Buchanan. By 1856, these regionally tentative beginnings of 1854 had congealed into a movement strong enough to hold a national convention and field a presidential candidate — John C. Fremont, who won 33% of the popular vote. The Democrats (and Buchanan) got 45%, and Know- Nothings (nativists) got 22%. The Whigs were finished. And within the Know-Nothings, north-south factionalism started to develop. It was simply a matter for the Republicans to hold together for another four years, for the 1860 election.

The nationally victorious Republican Party of 1860 was the end of a process at lease going back to 1848. The creation of this party (rooted in the movement to halt slavery in the new territories) did not win the Civil War. That was done by armies. But this new party was a necessary stage in the preparation for civil war, enabling society to separate out the conflicting elements and to define a causus belli: which mode of production would prevail — chattel slavery or industrial capitalism and labor power sold in the market place.

The Republican Party in those formative years, to the dispair of the radical Republicans, diluted much of the abolitionists’ direct invective against slavery as it existed. The Emancipation Proclamation came only in 1863 and left untouched slaves owned by Southerners who had resumed their loyalties to the Union.

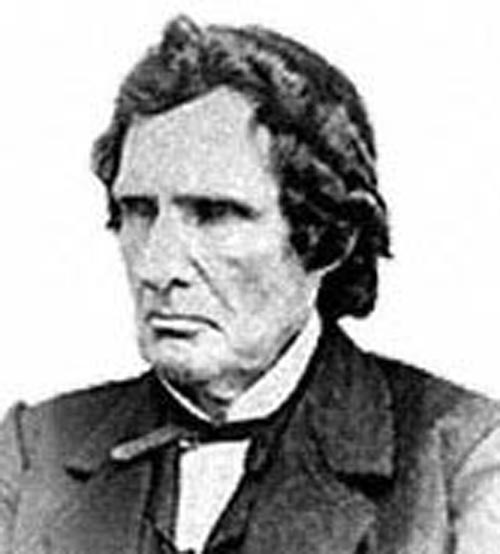

Long before he was elected to the U.S. Congress from Pennsylvania, Thaddeus Stevens (depicted in the current movie "Lincoln" as the leader of the hard abolitionist wing of the Republican Party) was a "progressive" in every sense of the word. His work in the Pennsylvania legislature promoted free public schools as an integral part of democracy during the same years he became a noted abolitionist. The movie "Lincoln" has revived historical interest in the career of abolitionist leaders like Stevens, who went so far in his beliefs that upon his death he was buried in the "Colored Cemetary" in his hometown of Lancaster Pennsylvania. And the Republican Party, despite its slogan of “Free Labor!” and the fact that wage earners in the North were attracted to it, was certainly not a labor party. It did, of course, have a populist appeal. The Springfield Republican proclaimed in 1857 that “property…has frequently stood in the way of very necessary reforms, and has thus brought itself into contempt.”

Long before he was elected to the U.S. Congress from Pennsylvania, Thaddeus Stevens (depicted in the current movie "Lincoln" as the leader of the hard abolitionist wing of the Republican Party) was a "progressive" in every sense of the word. His work in the Pennsylvania legislature promoted free public schools as an integral part of democracy during the same years he became a noted abolitionist. The movie "Lincoln" has revived historical interest in the career of abolitionist leaders like Stevens, who went so far in his beliefs that upon his death he was buried in the "Colored Cemetary" in his hometown of Lancaster Pennsylvania. And the Republican Party, despite its slogan of “Free Labor!” and the fact that wage earners in the North were attracted to it, was certainly not a labor party. It did, of course, have a populist appeal. The Springfield Republican proclaimed in 1857 that “property…has frequently stood in the way of very necessary reforms, and has thus brought itself into contempt.”

The Republican Party’s main appeal was to the small, entrepreneurial businessman, the family farmer, and a Puritan work ethic that found living off the toil of slaves abhorrent.

With all its warts, it was a new party. The falsehood should not be perpetuated that there has never been a successful third party in U.S. history. There was one, and it was as real as the Civil War.